This is Part 2 of 2. These links will quickly take you to your topic of interest in either part 1 or part 2.

On this page: Silk, Spinnerets • Webs • Reproduction • Lifespan, Foods, Predators

Part 1: History, Physical description, Senses, Communication

Spiders are fascinating animals! Just consider: They have spinnerets that act like a Tommy Gun, firing silk strands stronger than steel. Their webs are intricate works of art. And their bodies are a peculiar mix of the expected and bizarre!

Spinnerets and silk

Ah, the spinnerets! These are the organs through which a spider produces its remarkable silk threads. Conveniently located at the rear of the spider’s abdomen, on the underside, they come in pairs, typically three, but also two or four, depending on the species. Amazingly versatile, the spinnerets can move independently and in a coordinated way.

Silk glands

There are seven types of silk glands, and no spider has all of them. These glands produce proteins and other organic molecules that flow in liquid form through tiny tubes to the spinnerets. As the mixture moves along, a process removes water from the proteins and adds hydrogen. The result is an acidic fiber that solidifies as it exits into the air through the spinnerets.

Each silk gland produces silk used for a different purpose: attachment, dragline, web frame, wrapping, sperm webs, egg cocoons, and sticky silk. Silk threads are about one-millionth of an inch thick, but spiders can use muscles and valves in the necks of their spinnerets, singly or in combination, to thicken them.

All spiders produce silk, but they use it in many ways and for different purposes. They use it for draglines, but not all of them build webs. Males use silk to spin a sperm web before mating, and all females spin a silk cocoon around their eggs. Some spiders use silk to build shelters. Spiders can be thrifty–those that make webs will often eat them when they degrade to reuse the protein.

Silk vs. steel

Spider silk is stronger than steel on a weight basis! If you could compare a steel rod and a silk rod of the same weight, the silk would be stronger. It’s amazingly elastic, too, able to stretch up to many times its original length. The thread of the Indian Cooperative Spider, Stegodyphus sarasinorum, for example, is said to stretch up to twenty times its original length.

Spider webs

Not all spiders build webs, but those that do instinctively know how to. Webs may be relatively simple or very elaborate. Different species create differently patterned webs. Some spiders build a web that looks like something painter Jackson Pollack might have created–a tangle of silk threads all dressed up with nowhere to go—all they need is a splash of color! Some spiders attach a mass of silk to the corners of rooms–they’re the cobwebs we notice up there once they start accumulating dust.

The web of a funnel-web spider. The spider waits at the bottom of the hole for prey to land on the web, then dashes out. (OakleyOriginals / Flickr; CC BY 2.0)

Sheet web spiders create sheets of silk between tree branches, on shrubs, and in other suitable places. Some webs are triangular, some funnel-shaped. The webs of bola spiders (in the genus Mastophora) are a single strand of silk. And there are many other shapes, too. With some exceptions, a spider’s web can help identify it.

A web’s purpose is to capture prey. When an insect gets caught in its sticky strands, the spider rushes to it and injects venom to kill it. Some spiders wrap their prey completely in silk to immobilize it while it dies. Webs are also used for courtship rituals and for securing egg sacs. The most noticeable webs in our yards are the circular ones made by orb-weaving spiders (Araneidae, Tetragnathidae, Uloboridae).

How an orb-weaver starts a web

Ever wondered how a spider strings a web from here to clear over there, with nothing but space in between? It’s so simple, yet clever; you’ll be impressed. Here’s how it’s done:

An orb-weaver is one of the numerous spider species that spin spiral webs. You’ve probably seen one of their webs in your yard or garden. At night, from a suitable starting point, such as the branch of a tree, the spider releases a long thread of silk from a spinneret into the wind. It takes only the slightest wind movement to carry it. The thread weighs so little that less than 18 ounces (500 grams) would completely encircle the Earth. The plan is for it to snag on something, anything. If it doesn’t, it may be pulled back and eaten for its protein content. The spider will try again.

Once something catches the thread, the spider pulls it tight and securely anchors it. Now, it’s attached at both ends. The spider reinforces the thread by repeatedly crossing back and forth while laying down more silk. That’s important, as the “bridge” line will support the weight of the completed web.

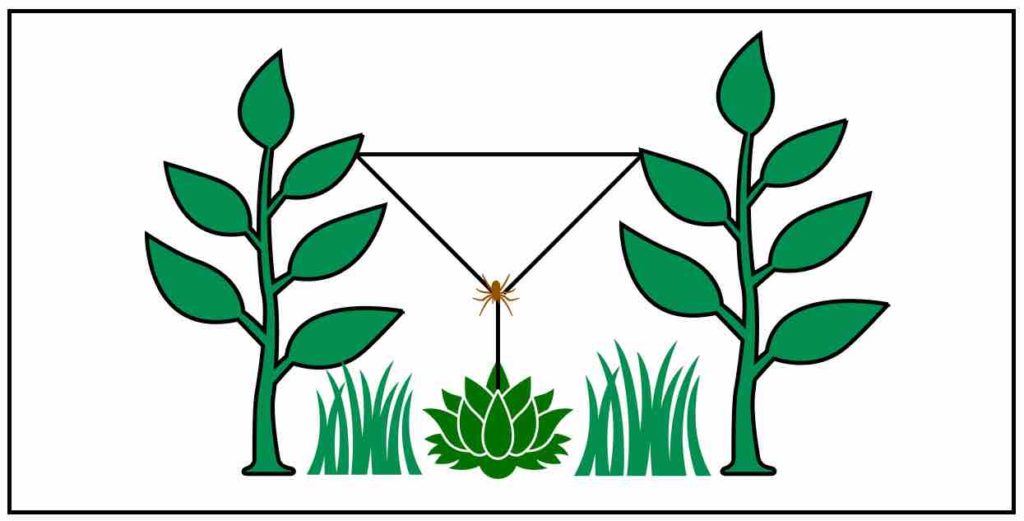

Next, the spider suspends a line of silk across the bridge very loosely so that it sags in the center when the spider crawls down it. A “V” has now taken shape. At the bottom of it, the spider attaches another line, which it runs to a suitable anchor point. The structure is now a “Y,” which forms the first three radial threads of the web.

The first three radial threads of a spider’s web form a Y-shape (WelcomeWildlife.com; CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Still more to do

Once that’s done, the spider is ready to thread the sides of the web and add more radial lines. That work is followed by laying down sticky threads that start near the center and spiral outward to cover much of the web. The web is now complete, the final construction consisting of a supportive frame of top, sides, and radial threads overlaid with sticky spiral ones for catching prey.

Once finished, the spider sits motionless in the (non-sticky) center, head down, queen of her domain (males tend to wander instead of building webs), waiting to feel vibrations on the sticky threads–an announcement that prey is trapped! The spider will rush to it by stepping on the radial threads and frame while avoiding the sticky spiral ones.

Orb-weavers don’t generally get stuck to their webs because, first of all, they know where to step. But they also have tiny barbs on the bristles of their feet that keep them from sliding into sticky silk. They also move their hind legs at an angle that somehow minimizes the stickiness effect. Despite these advantages, accidents do happen and these spiders have a special oily coating that seems to make them less likely to get permanently trapped.

When morning comes, the spider slips away to a resting spot out of sight. If the web doesn’t get too damaged, it may be used again and again and even patched up a bit. Some spiders eat their web each morning, except for the framework, and re-spin it every night.

Reproduction

Males actively search for females, and courtship differs depending on the species. For example, males of some species “dance” or wave their pedipalps, and male “gift-giving spiders,” Paratrechalea ornata, catch prey and wrap it up as a gift of food. (Although some are cads—if they’re hungry, they may eat the victim, then present its wrapped carcass as a gift!) Once mating commences, it may take only seconds or many hours, depending on the species. It’s a myth that females always eat the males after mating; that doesn’t commonly happen, but males do avoid females that look undernourished! Females may mate only once, with the same male more than once, or even with several different males.

Spiders reproduce in a rather weird way because males lack a penis. It’s clear from the billions of spiders in the world that the missing member isn’t an impediment. Like so much else about them, there’s a curious workaround for that.

A curious reproductive adaptation

Males extrude sperm through a furrow in the underside of their abdomen onto a small web they have constructed, called a “sperm web.” They then draw the sperm, probably by capillary action, into organs called palpal bulbs, located at the tip of their pedipalps. Once done, mating can commence. The male inserts the tips of his pedipalps into the female’s external genitalia, called the epigyne. The epigyne is a small area of hardened tissue on the underside of her abdomen, near the book lung.

In most groups, the male inserts his left pedipalp into the left opening of the female’s epigyne and his right pedipalp into the right opening. With some others, though, the female’s epigyne and the male’s pedipalps are so intricate they work like a key and a lock.

Insemination and egg-laying

Sperm moves from the epigyne into storage receptacles called spermathecae, where it will stay until the female is ready to use it. When she’s ready to lay eggs, she releases some of the stored sperm to fertilize them as they leave her ovaries to pass out of her body. A female can store enough sperm from a single copulation to last her entire life. Expelled eggs, which often look like drops of liquid, are deposited onto a silk pad and then wrapped in multiple layers of her silk. The egg sacs are round or disk-shaped.

Egg sacs

Females of some species stick their egg sacs to a surface and abandon them. Others guard them zealously, lay them on their web, or carry them around between their chelicerae or attached to their spinnerets.

A single egg sac may contain hundreds or thousands of eggs. If a female constructs several sacs, each succeeding one will contain fewer eggs. In many species, the female dies after laying her last egg sac. Others, however, live one or two years and take care of their offspring for a period after they hatch.

Most eggs hatch when the weather is warm. In spring and summer, eggs may hatch in two to four weeks. If they hatch in the fall or winter, the spiderlings stay in their egg sac until spring.

Good mothers and spiderlings

Spiderlings are usually on their own from the time they leave their egg sac, but those in a group of spiders called wolf spiders ride around on their mother’s back for about ten days. Comb-footed spider mothers (family Theridiidae) feed their spiderlings with liquid from their mouths. In 2018 surprised researchers in China discovered that Toxeus magnus spiderlings suckle a high-protein “spider milk” from their mother’s egg-laying organ for 40 days.

Most spiderlings leave their birthplace by “ballooning” away: They climb up a tall object, such as a branch, tree, or fence post, and let the breeze pull silk from their spinnerets to use as a “dragline.” A newly hatched spider weighs so little that as the dragline lengthens, it eventually pulls the tiny body up and away. At some point the airborne spider catches on something and from there begins its independent life.

As they grow, baby spiders outgrow their skin and must shed (molt) it several times. The bigger the spider gets, the more times it molts.

Lifespan

Most spiders die from predation or other causes before they reach their potential lifespan of a year or two, but there are remarkable exceptions. Spiders in the infraorder Mygalomorphae, which tend to be big and hairy, live years longer—female tarantulas up to 30 to 40 years! A trapdoor spider living in the wild was monitored all its life by renowned arachnologist Marjorie York Main—it died in 2016 at the ripe old age of 43 years after being stung by a wasp. Whether captive or not, male spiders have shorter lives than females. One reason is that they move about in search of mates and face more attention from predators.

Food sources

Spiders feed primarily on insects but also on other spiders. Large spiders may catch small animals, such as lizards, frogs, baby snakes, and baby rodents. Large orb-weavers will feed on small birds or bats caught in their web. One exception to an all-meat diet is the male Goldenrod Crab Spider, Misumena vatia, known to feed on pollen while it sits on flowers awaiting insects. There are four typical ways that spiders catch prey. Depending on the species, they:

- Live in a silk-lined burrow and leap out to catch prey.

- They lie in wait to ambush prey in places such as plants, flowers, the ground, under stones, and tree bark.

- Actively search for prey.

- Spin a web to entrap prey.

Predators and defenses

Birds, frogs, toads, snakes, lizards, ticks, and wasps prey on spiders. In some countries, monkeys do, too. And spiders have to watch out for other spiders, too. Daddy Longlegs (which look like spiders but are not) prey on them. Roundworms and mites parasitize spiders.

A spider’s best defense is to hide. Many have camouflage coloration that hides them in plain sight. Or, they may run into a crevice, under bark, under a rock, or anywhere else a predator may not be able to enter. Some “trapdoor spiders” construct burrows with hinged doors made of silk, soil, and vegetation—when threatened, they can run inside and tightly close the door. Golden orb-weavers of Asia coat their webs in a chemical that repels many insect predators. Wolf spiders, Lycosidae, will bite in defense. Tarantulas and others in the family Theraphosidae have urticating (stinging) hairs they flick at predators.

More reading

| Spider basics, body, behavior – Part 1 |

| If you see this, it must be fall: garden spiders |

| Tips for identifying spiders, insects |

| The fascinating life cycle of insects |