This article was updated on April 12, 2024.

The lawn-care technician in this photo is dressed for hazardous duty, and for good reason. If you do nothing more than say “no” to the use of pesticides in your yard, you’ll have done an excellent thing for wildlife and pets, the environment, and, not incidentally, your own health.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines pesticides as “… (with certain minor exceptions) Any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, repelling, or mitigating any pest. Any substance or mixture of substances intended for use as a plant regulator, defoliant, or desiccant. Any nitrogen stabilizer.”

That means using herbicides, insecticides, rodenticides, or any other “cides” in your yard will kill or incapacitate. Even fungicides intended for fungal infections on plants can be highly toxic to other organisms, including aquatic plants and animals. And that’s not the limit to damage from pesticides. Humans are affected, too.

Scary stuff: the EPA warnings

The EPA warns us to use impermeable gloves, long pants, and long-sleeved shirts when using pesticides. Furthermore, they’re not to be used on windy days, around children or their toys, pets, a pool, or the garden. Food should be covered and the products locked away from youngsters, who should be taught that pesticides are poisonous. The EPA says pesticides can poison through inhalation, tissue absorption, or ingestion.

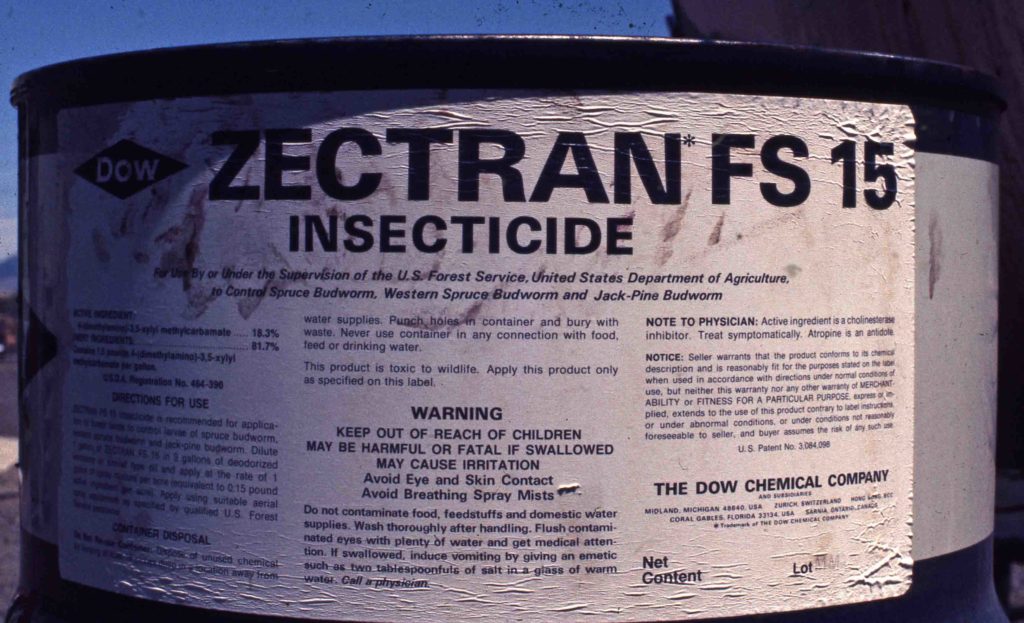

Even if we were to assume the EPA was being overly cautious, the labels on the product containers themselves are scary enough. These chemicals obviously have no place in our lives or a backyard wildlife habitat.

Pesticides are derived from chemical warfare agents

Many pesticides are organophosphate or n-methyl carbamates (as shown in the photo above). An interesting (alarming?) thing about them is that they were originally derived from World War II chemical warfare agents. They kill by breaking down certain nerve impulses, eventually leading to irreversible physiological damage.

If you became poisoned by one of these chemicals, you’d experience nausea, vomiting, heavy salivation and drooling. You’d wheeze and have difficulty breathing. Seizures would begin, then a lapse into a coma. Finally death. Even mild poisoning can cause muted variations of these symptoms, and most of the time, the symptoms are not recognized as being connected to pesticide use.

They’ll keep coming

Killing pests won’t solve a pest problem, anyway. More pests soon fill the void, and more pesticides are needed. The best way to deal with them is through non-chemical or natural repellents. For example, to discourage rabbits, you can broadcast blood meal on the ground around plants, fence off precious plants, or even have enough plants to share with them. Undesirable insects on plants can be hosed off or, better yet, make your yard an inviting host to their natural enemies. (For example, ladybugs will keep aphids under control.) Pigeons can be discouraged with roof spikes. Avoid stacking firewood or debris beside your house foundation to keep mice, rats, termites, and other insects away. There’s a humane solution to any pest problem.

Pesticides have unintended consequences

Every year, as many as 67 million birds die from pesticides. It’s a staggering number, and some researchers think it may be more than that. Almost no one intentionally kills a bird, but they ingest residue when preening their feathers, drink contaminated water, eat contaminated prey, mistake pesticide granules for seeds (a single granule of some pesticides is lethal to them), absorb them through their skin, or inhale them. As of now, forty active ingredients in pesticides kill birds.

It isn’t just birds that suffer. Pesticides drift. Fine particles ride the wind and strike non-targeted species, including humans. All wildlife may be harmed by even trace amounts of some pesticides. Poorly timed or careless spraying of insecticides may kill harmless insects, like honeybees and other pollinators of flowers.

Did you intend to kill the Monarch Butterfly?

You may intend to kill only the aphids decimating a red milkweed plant, but unless applied very carefully, even a slight bit of wind will carry the poison to nearby plants. Not only that, but all insects on the milkweeds will die, including any Monarch Butterfly caterpillars caught in the spray. Insects on nearby plants may die, too. Until it breaks down, which can be as quickly as 24 hours or as long as many years, the product will kill all unlucky insects that crawl on, land on or brush against those plants.

Herbicides, too, can have unintended consequences when they drift and damage neighboring plants and flowers. Then there are the rodenticides, which are formulated to be tasty. They don’t selectively kill only mice and rats; they can also kill other mammals, including your pets. In 2017, just watering the ground where a pesticide had been sprayed led to the death of four children in Texas when the action produced a toxic gas.1 Worldwide, every year, 220,000 people die from pesticide poisoning.

Pesticides in your home: a case for reconsideration

Some outside critters inevitably manage to get inside houses. Like pesticides, they ride in, blow in, or crawl in through what seems like impossibly minuscule holes and cracks in walls and foundations. Or, they may just march in through open doors and windows, like General Sherman taking Atlanta. Whichever, a typical response is to swat, stomp, or spray them to death. But there’s a safe alternative to this: catch and release them outdoors.

Pesticide use indoors is a vicious cycle. It kills but does not stop others from entering. If only we could post a sign at all entrances in pest language warning them away! Instead, these unwelcome guests continue to find their way inside, where insecticides will kill them, but only until the toxicity of the product breaks down. These home products have become safer for humans, but they must be reapplied, and the cycle begins again if the goal is to stay pest-free. While the bugs are dying, families are repeatedly exposed. The EPA says indoor air quality from repeated exposure can result in damage to the liver, kidneys, and endocrine and nervous systems.2

Especially at risk: children

Tests on animals have shown that pesticides attack the developing brain, leading to lifelong behavioral problems. A comparison study of preschool children in a farming community using pesticides and another farm did not reveal striking differences. The children in the pesticide community had impaired hand-eye coordination, less physical stamina, short-term memory problems, and difficulty drawing. They also were more aggressive and anti-social compared to children in the other community.3

There are at least 101 common pesticides known to be probable human carcinogens, and some are chemicals that increase the risk of several forms of cancer. At least five studies have found a link between mothers who used pesticides while pregnant or nursing and their children who developed acute leukemia. Insecticide and herbicide use are also linked to disruptions in hormonal function, birth defects, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths.

Pesticides in drinking water

Although the USDA appears to be doing a good job of regulating pesticides in human food, they can be found in the drinking water of people who live in an agricultural community, from chemical runoff.

Even if you ban these chemicals indoors, they’ll invite themselves in. Particulates ride in on the gentlest breeze through open doors and windows. They hitch a ride on your clothes and cling to your shoes. They’re transported in on your dog’s hair and the flower bouquets you pick from your garden. They’re on your children’s toys. They circulate throughout your house through the ventilation system and accumulate at high concentrations near the floor where your pets and toddlers play. They drop to your countertops and coat your furniture. Even the dust in your house will collect pesticide particulates.

Combat critters without pesticides

Indoors, remove what attracts pests, like sources of food and water. Clean up food spills immediately with soap and water, vacuum regularly, seal food containers tightly, and seal all cracks and openings around the foundation to prevent access. When they show up (and they eventually will), relocate them outdoors (you’ll find there’s some satisfaction in knowing you saved its life.)

Conclusion

We may not be able to protect the rest of the world from pesticide overuse, but as masters of our own domain, we can do our best to protect the outdoors and the indoors.

1 Texas pesticide deaths

2 EPA: Indoor Air Quality

3 NIH: Pesticide exposure and child neurodevelopment

In your yard: moles and shrews

In your yard: harmless guardians of night skies