Millipedes, with their elongated bodies and many, many legs, may be alarming, but they’re good to have in your yard. They’re harmless to humans, too. They’re detritivores that primarily feed on decomposing organic matter, which returns valuable nutrients to the soil and benefits plant growth. In addition, some species also consume fungi and other microorganisms.

Fossils of the first millipedes suggest they were among the first animals to colonize land. They have an ancient lineage, with their origin tracing back to the Silurian Period, around 428 million years ago. Early ancestors were much larger than most modern species. A fossilized fragment of one found in England suggested its length to have been around 8.5 feet (2.6 mm) long, that of a small car.

Millipedes aren’t insects. They belong to various subclasses in the order Diplopoda and, surprisingly, are more closely related to shrimp, crayfish, and lobsters than insects. There are about 12,000 known species, and it’s estimated that tens of thousands more have yet to be discovered. (And rediscovered: in 2024, a species 10.8 inches (27.5 cm) long, Spirostreptus sculptus, that had been “lost” for 126 years was found in Madagascar.)

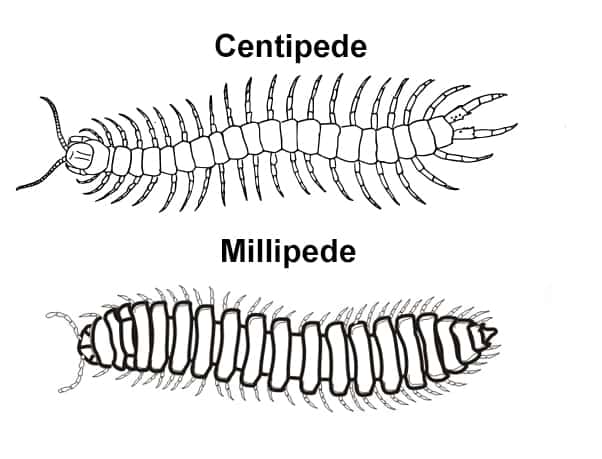

Differences between millipedes and centipedes

Millipedes and centipedes are often confused due to their similar elongated, segmented bodies. However, they exhibit several key differences. Millipedes typically have two pairs of legs per body segment. They move slowly and are primarily detritivores, feeding on decaying plant material. In contrast, centipedes have one pair of legs per segment and are fast and agile. They’re carnivorous, preying on insects and other small animals using their venomous pincer-like front legs (forcipules). Millipedes have cylindrical bodies and prefer moist environments.

Centipedes have a flattened body and can be found in a wider range of habitats. Additionally, millipedes release toxic or foul-smelling chemicals as a defense, while centipedes rely on their speed and venom to deter predators.

Would you believe 1,306 legs?

The largest millipede in the world is the African Giant Millipede, Archispirostreptus gigas, which can grow up to 15.2 inches (38.5 cm) in length and have between 200 and 300 legs. In an odd twist on size, one of the world’s smallest millipedes, Illacme plenipes, inhabiting central California, has up to 750 legs while measuring just 1.2 inches (3.0 cm) long!

Millipede, Illacme plenipes, female, only 1.0 inch (25 mm) long. This particular one has 618 legs. (Daniel Mietchen / Wiki; CC BY 3.0)

The largest millipede in the United States is the American Giant Millipede, Narceus americanus, up to 4.0 inches (10.2 cm) in length, with adults having 180 to 240 legs. The champion of leg count, however, is a Eumillipes persephone found in western Australia, with a whopping 1,306 legs—the most of any known animal.

Where to find millipedes

Millipedes have a global distribution and thrive in various environments, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands. In your yard, look for them under piles of leaves and grass clippings. Slowly turn over rocks, logs, and landscape timbers. You might also find them under thatch between the grass and the soil in the lawn.

Physical characteristics

Millipedes have elongated, cylindrical bodies composed of numerous segments. Most segments have two pairs of legs, giving them a distinctive, multi-legged appearance. Depending on the species, the number of legs typically ranges from 34 to 400, with some exceptions, including those noted above.

Millipedes come in various colors, from shades of brown and black to more vibrant hues like red, orange, and yellow. Some species have banded or spotted patterns, while others may have a uniform coloration. And there are those with an appearance you don’t expect, such as the bristly ones in the order Polyxenida.

The millipede’s exoskeleton is hard and segmented, providing both protection and structural support. The head is equipped with a pair of short, segmented antennae that sense their surroundings. They also have simple eyes, or ocelli, which are clusters of light-sensitive cells that detect changes in light intensity rather than forming detailed images. Their mouthparts are adapted for chewing, allowing them to break down plant material effectively.

Millipedes do have a brain, and you may wonder if they display any intelligence. A chat forum here discusses that, and the consensus seems to be that captive millipedes can display a “personality” that suggests some sort of intelligence.

Communication

Millipedes communicate primarily through chemical and tactile signals. Chemical communication involves the release of pheromones, which are chemical substances that can influence the behavior or physiology of other millipedes. These pheromones are used for various purposes, including attracting mates, signaling danger, and marking territories. For example, during the mating season, males release pheromones to attract females and initiate courtship.

Tactile communication involves touch. They use their antennae to explore their surroundings and interact with other millipedes. They may touch and tap with their antennae to convey information when encountering each other. This tactile interaction helps them recognize potential mates or competitors and can play a role in their social behavior.

In addition to chemical and tactile signals, some millipedes can produce sounds by rubbing their body segments together, a behavior known as stridulation. While not all species do this, it can be used to communicate with potential mates or deter predators.

Reproduction

Millipede mating is a fascinating process involving intricate behaviors and specialized anatomical structures. During courtship, the male millipede begins by using tactile and chemical signals to attract a female. He often taps and strokes her body with his antennae, sometimes releasing pheromones to entice her further. Once the female is receptive, the male mounts her back, aligning his body with hers.

The male possesses specialized legs known as gonopods, which are modified for transferring sperm. These gonopods are typically located on the seventh segment of his body. He uses these appendages to scoop up sperm packets, or spermatophores, from his gonopore, an opening on the underside of his body. The male then carefully inserts the spermatophores into the female’s gonopores, which are located on the third segment of her body.

Female chooses when to fertilize her eggs

This process requires precise coordination, as the male must ensure that the spermatophores are securely transferred. The female then stores the sperm in specialized structures within her body until she is ready to fertilize her eggs. This spermatophore transfer can take several minutes to a few hours, depending on the species.

After successful mating, the female lays her fertilized eggs in the soil or decaying plant material. She often creates a small nest or burrow to protect her eggs, providing them with a safe and moist environment. The number of eggs laid can vary widely, ranging from a few dozen to several hundred, depending on the species.

This reproductive strategy, involving the direct transfer of sperm and subsequent egg-laying in a protected environment, helps ensure the survival of the next generation of millipedes. Millipedes’ intricate mating dance and specialized adaptations highlight the animal kingdom’s complexity and diversity of reproductive behaviors.

Factors such as habitat, diet, and the presence of predators or environmental stressors can influence a millipede’s life span, but most live five to ten years.

In the winter, millipedes look for places to keep them from freezing. They may burrow into the soil, take refuge under layers of leaf litter, crawl into rocks and other natural debris, or inside rotting wood or tree crevices. Sometimes, they move into basements and crawl spaces.

Predators

Millipedes have a range of natural predators, including birds, frogs, small mammals, and other arthropods.

Defenses

To defend themselves, millipedes may coil into a tight ball to protect their legs and vulnerable underside. Some species can secrete toxic chemicals, including cyanide, from their body segments. An example is the Yellow-spotted Millipede, Harpaphe haydeniana, also called the Cyanide Millipede and Almond-scented Millipede.

The quantity of cyanide produced is small and not dangerous to humans. However, direct contact with the secretions can cause skin irritation or allergic reactions in sensitive individuals. To avoid any potential irritation, it’s always a good idea to wash your hands thoroughly if you handle one.

All about earthworms All those plants in your yard? Surprisingly brainy! Ins and outs of an insect’s anatomy Butterflies survive against colossal odds Learn about gnats and other no-see-ums In your yard: pill bugs (roly-poly bugs)