It’s a veritable giant among men! How else can the sight of a body weighing barely one-and-a-half ounces, make grown people shriek and dash for cover?

There are theories about our overreaction to mice. One is that it’s just the element of surprise. Their appearance is usually sudden and followed by quick movements, which can be startling. Women tend to get more frightened than men, and there’s possibly a reason: Scientists have found that mice are less stressed by females and they tend to linger marginally longer around them. Male pheromones, on the other hand, are apparently more frightening to mice.

Aside from making us jump, the House Mouse and, indeed, all mice are just generally reviled if not feared. Their “beady” eyes, long, bald tail, and history of carrying diseases have ordained them as “vermin.” They’re also a great nuisance when they eat stored grains, damage root crops with their burrows, and invite themselves into houses. Except for, say, pet mice, you might wonder “What good are they?”

Surprisingly beneficial

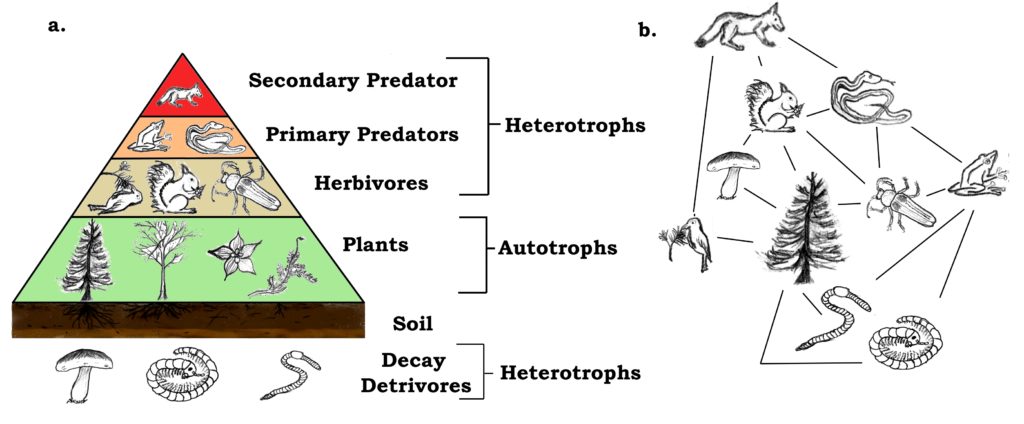

What many people don’t realize is that mice are a keystone species in virtually every terrestrial ecosystem in the world.1 Take a look at this food-chain pyramid It illustrates from plants upward each animal group that’s prey for the levels above it. Plants, at the bottom, are food for herbivores and they, in turn, are food for omnivores, and so on. Experts say a world without herbivores and omnivores, which includes mice, would ultimately lose all its carnivores, which includes humans. Uh, oh!

Mice are important for other reasons, too. They feed on pest insects, helping to keep those populations under control, and at a homestead level, they’re a help to gardeners because they eat weed seeds.

Background

The best-known mouse is the House Mouse, Mus musculus (MUSS MUSS-kuh-lus), which first made its appearance in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India around 500,000 years ago, during the Cambrian Period, when most major animals began to appear.

House mice in recent history have traveled with humans all over the globe and exist everywhere, except Antarctica. Hardly any environment is too forbidding as long as there’s a food source.

Mice belong to the scientific order Rodentia (row-DENCH-uh), which includes squirrels, chipmunks, beavers, prairie dogs, gophers, groundhogs, chinchillas, and others. A child’s pet hamster, gerbil, guinea pig, or rat is also a rodent. Rodents are the largest group and population (40 percent) of mammals. Out of 5,416² species of mammals, about 2,200 are rodents.

Mice belong to the suborder Myomorpha and the family Muridae (MYUR-uh-dee). In addition to the House Mouse, there are many subspecies, among them the East European House Mouse (Mus musculus musculus) and the West European House Mouse (Mus musculus domestius), with all being very similar.

House Mouse vs. field mouse

Many people think that the House Mouse is a Field Mouse that has moved indoors. But, a House Mouse really is a House Mouse. The “Field Mouse” name belongs to various other rodents, depending on where you live in the world. In Europe, for instance, any rodent in the genus Apodemus is a Field Mouse. In North America, a Field Mouse is any one of a number of small rodents called voles, particularly the Meadow Vole, Microtus pennsylvanicus.

Physical description

The adult House Mouse is small, only about 3.0–3.9 inches long (7.5–10 cm). The tail is 2.0–3.9 inches long (5–10 cm). Adults weigh only 1.4-1.6 ounces (40–45 g). They can squeeze through a dime-sized opening (0.71 inches = 17.9 mm) and juveniles can make it through a 0.25-inch (6.3 mm) opening (about the diameter of a pencil). The size of their head determines the width they can enter.

Males and females, alike, are covered in sleek, short, light- to dark-brown hair. (Some subspecies have a light belly). They have a long, pointy snout, long whiskers, small eyes, and bald, round, relatively large ears. The tail is scaly and has sparse, brownish hair.

Among the characteristics that group all species of mice with other rodents is their teeth: a pair of sharp incisors (front teeth) in the upper and the lower jaws. The teeth are chisel-shaped with hard enamel on the front and softer dentin on the back, which makes them wear unevenly and maintain the chisel shape. The incisors grow continuously, but they’re kept from becoming too long by rodents’ habit of gnawing on hard things, as well as by the tough foods they eat. The need to gnaw can make rodents destructive, but it isn’t an option for them. If their teeth overgrow, they won’t be able to chew food properly and will starve to death.

Senses

The sense of smell is the House Mouse’s most robust sense. It isn’t developed at birth and does so slowly over the first 30 days of their lives, as babies begin to bond with their mothers. Researchers believe having to use smell to find their mother and identify her, as well as their siblings and home is a survival advantage. As adults, they rely on scent for finding food and mates, and for detecting the territorial markings of other mice.

House mice have excellent vision, but little or no color vision. Their hearing is superior and extends into the ultrasonic range–sound waves that are higher than humans can detect. They have an excellent sense of touch and use their whiskers to sense air movement and to feel around like cats do.

House Mouse or rat?

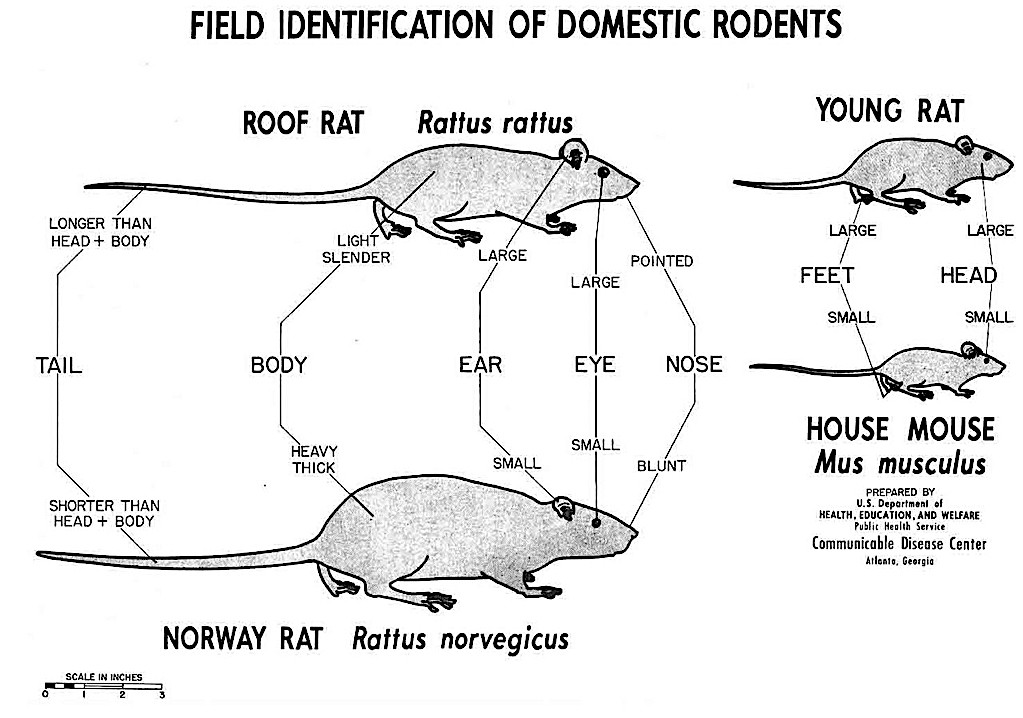

Here’s a guide to help you identify whether the critter that just raced out of sight is a mouse or a rat. Rats are considerably larger, even young ones, and have larger feet. They have a more rounded snout and may be white, brown, gray or black.

Behavior

House mice are nocturnal, but that doesn’t keep them from going outside occasionally in the daytime. Day or night, they don’t go farther than they need to obtain food, staying as close to their familiar territory, as possible, and routinely travel the same route, which is usually no more than about 30 feet (9 m) in diameter.

They leave dark, oblong 0.25-inch (6.4 mm) droppings along a well-traveled path, and males mark their territory with strong-smelling urine. Droppings are often what first alert homeowners to their new “lodgers.” The mice are more of a problem for people in winter because they move indoors, if they find a way, for warmth and food. Their droppings contaminate surfaces, but on a “personal” level they’re clean, routinely licking and grooming their hair, and they keep their nest tidy, as well. House Mice are active year-round, they don’t hibernate.

Sometimes they live together, and when they do, it’s usually in a group of one male, several females, and their offspring. They defend their home against outsiders.

Communication

Mice mainly rely on pheromones for social communication. The pheromones are produced by glands located in folds of skin in front of their genitals. Their tears, as well as the urine of males, contain pheromones. They have a musky odor detectable by humans.

Mice communicate vocally, too, by making soft chittering and squeaking sounds to each other in their nest, as well as when they’re hurt or scared. These sounds are audible to humans. They also have songs that are beyond our hearing, in the ultrasonic range. Some songs are produced exclusively by males and others only by females. Mouse’s ultrasonic song

Habitat, nesting

House mice are comfortable living around humans, and will gladly move into our homes and offices. Some spend their entire lives in a building, where they live in walls, under major appliances, in storage boxes and drawers, and upholstered furniture.

Most House Mice, though, live in crevices in rocks and woodpiles, in piles of debris, and sheds, barns, crawl spaces, and garages, wherever they can hide that’s near a source of food. If there’s no other suitable shelter, they may dig complex burrows. Even then, the mice usually live relatively close to buildings.

Their home usually has separate areas: a “pantry” for stored food and a place for nesting. They build nests made from soft materials, such as finely shredded paper or cloth. A nest will have several access points, not only as a convenience for entering but also for providing a quick exit if a predator comes around.

Reproduction

Males and females can mate any time of the year but most do so between late spring and early fall, particularly in the North. Courtship begins with male emitting ultrasonic calls in the range of 30 to 110 kilohertz. (By comparison, human vocal range is 300 to 3,400 Hz). He follows the female around, sniffing her, and may continue his calls even while mating. Females usually don’t make sounds as part of their mating behavior.

Females have five to 10 litters a year, which is a hedge against heavy predation. The gestation period is 19 to 21 days. Females are capable of producing 12 to15 offspring, but the average is five. The babies are bald at birth, their ears flattened and their eyes closed. Weighing only about 0.3-ounce (8.5 g), they’re completely helpless.

They rapidly grow, however, and about 10 days later they’re covered with hair. At two weeks they open their eyes, and at three weeks they’re weaned. At five to eight weeks they’re ready to move to their own territory and mate. Sometimes, young females will live near their mother.

Food Sources

House Mice are omnivores, meaning they eat both animal and plant foods. Every part of a plant—leaves, roots, stems, seeds, fruit, grains, and nuts — is part of their diet. They supplement that with insects, carrion, pet food, and just about anything that people will eat.

They eat a couple of main meals a day, at dawn and dusk, but they also like to snack periodically. So, when they find extra food, they store it in their pantry. This habit may have given rise to the origin of the word mouse, which derives from the Latin and Sanskrit mus, meaning “to steal.” Mice drink water but mostly obtain moisture from the foods they eat.

Defenses

Speed and agility are the House Mouse’s best defenses. They can run at 8 miles per hour (13 kmh), climb nearly any slope with a roughened surface, and run along thin wires or ropes. Add the ability to jump 12 inches high (30 cm) and swim very well, too, and you’ve got an Olympics-grade animal! Oh, and they also can bite.

Lifespan

Most House Mice don’t live beyond a few months. Despite their laudable athletic abilities, they face long odds in the wild. They’re under constant siege as prey for innumerable other animals and threatened by environmental hazards, too. Twelve to 18 months is a long life out there. But even under optimum conditions, they have short lives. Pet mice live an average of only two to three years. There’s a record of one captive House Mouse that lived just over four years.

Predators

A broad range of animals prey on mice. Mammals, including foxes, weasels, ferrets, cats, and even rats. Also snakes, lizards, hawks, and owls. Humans, too.

Diseases

House Mice (and other rodents) don’t carry rabies. There’s no reason why they can’t, but they never do and aren’t a risk. The risk lies in other viruses and bacteria they may carry. The House Mouse does not carry the well-publicized hantavirus, but according to the US Centers for Disease Control, it’s associated with the Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, and the Salmonella, Leptospira, and Tularemia bacterium.

Keeping House Mice away

Remove resting and nesting places and accessible sources of food, particularly around the perimeter of the house. Seal trash cans tightly, keep clutter away, pick up piles of debris, and don’t leave doors standing open. If pets are fed outdoors, then clean up any leftovers.

¹ Nature: Mice play main role between plants, predators in every terrestrial ecosystem

² Mammal Species of the World, 3rd Edition (Wilson and Reeder, 2005). The figure changes as new species are described.

Mice: frequent questions

Dam! It’s the beavers!

Best native grasses for a yard

Diversity in similar-looking rodents: mice, rats, voles