Jump down to learn this about honeybees: Background • Physical characteristics • Head, thorax, abdomen • Senses • Response to bee sting • Behavior, castes • Reproduction • Swarming • Dances, Types • Foods, Predators, Defenses, Lifespan

One pint of honey takes hundreds of honeybees gathering nectar from two million flowers (© iClipart)

How honeybees pollinate

Honeybees have fuzzy bodies that carry an electrostatic charge, which causes pollen (male plant parts) to stick loosely to them like static does on our clothes. Some of the pollen is brushed off onto female plant parts as the bees move from flower to flower. It’s so simple yet so vital.

Background

Honeybees are in the order Hymenoptera (hy-men-OP-ter-uh), which is from the Ancient Greek hymen + pteron, literally meaning “membrane wings.” The order also includes wasps, ants, and sawflies. Bees evolved from a wasp-like ancestor and have been around since the middle of the Cretaceous Period, about 120 to 130 million years ago. Scientists think bees and flowering plants might have evolved together. Kind of makes sense, doesn’t it?

There are about 20,000 bee species in the world. Of these, honeybees represent seven species and forty-four subspecies, all in the genus Apis. The most common one is the Western Honeybee, Apis mellifera, which inhabits the U.S., Europe, Australia, Africa, and part of Asia. Other major species are the Small Honeybee, Apis florea, Giant Honeybee, Apis dorsata, and Eastern Honeybee, Apis cerena, all found primarily in Asia. Honeybees have a broad range, from regions with cold climates to the tropics.

Physical characteristics

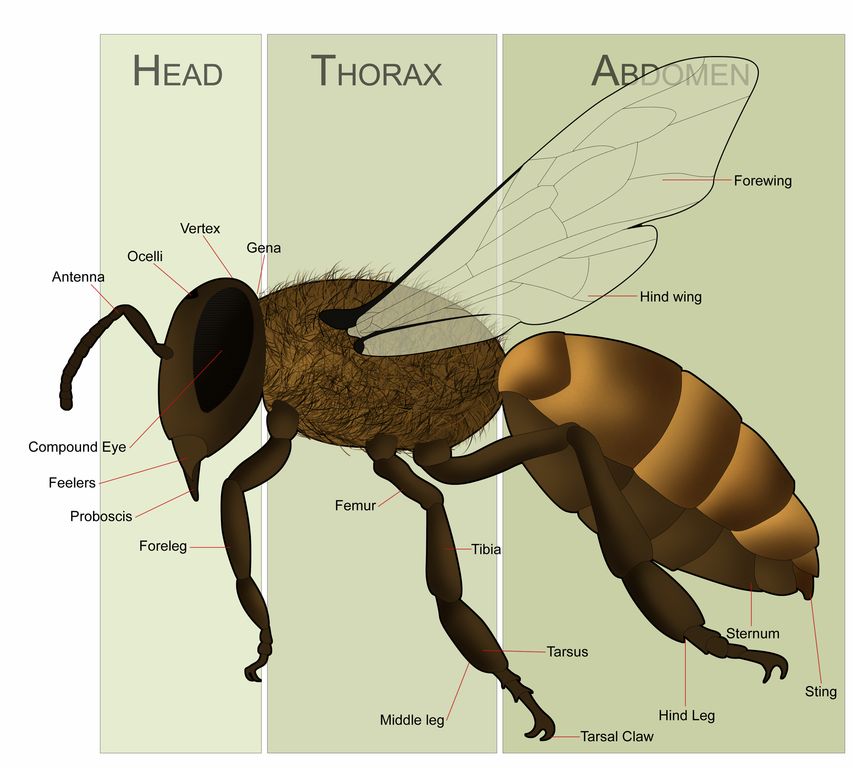

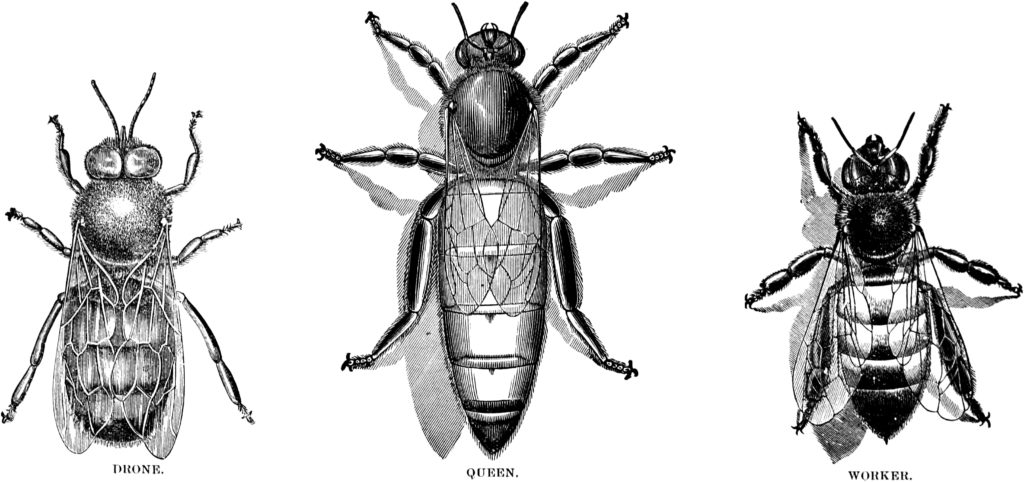

Honeybees, like other insects, have three body sections: head, thorax, and abdomen. Their body is oval-shaped, covered with hair, and has light and dark stripes. “Worker” bees (always females) are the smallest in a colony. Each weighs only .00025 pounds (0.1134 g)1, is 0.4 to 0.6 inches long (10.2–15.2 mm), and has a barbed stinger at the tip of her abdomen. Males, called drones, are slightly larger and don’t have a stinger. The “queen” bee, the only bee in a hive that lays eggs, is about twice as large as a worker, with an abdomen that’s more pointed at the tip, and she can sting if necessary.

The honeybee’s skeleton, called an exoskeleton because it’s on the outside of its body rather than inside like a human’s, is made up of hard, moveable plates of chitin. (Other animals with chitinous exoskeletons include crabs and lobsters).

Head

On the head are two antennae, two large compound eyes, and three simple eyes. Each compound eye is made up of about 150 small eye parts called ommatidia, which specialize in seeing patterns and colors in ultraviolet light. The bee’s mouthparts are complex and can both chew and suck. They consist of a pair of mandibles (jaws), a tongue called a gloss, as well as a labrum and two maxillae, which are like lips and support a proboscis (pro-BOSS-kiss), which is tube-shaped for sucking nectar.

The bee’s brain is made up of neurons that communicate with each other to perform complex tasks. Research in 2018 discovered that bees understand the concept of “nothing” and that zero is less than one. (It takes children several years to learn this.) In 2019, it was found that bees can also be taught to add and subtract! See how that was done. It seems there are no dim-wits in the hive!

Thorax

The second body section is the thorax, which has two pairs of wings and three pairs of legs attached. The wings are extremely thin and fragile, but they move with amazing speed—230 beats per second!2 A row of hooklets called hamuli (HAM-u-lie) on each of the back wings attach to a fold on the edge of the front wings and hold them together when they’re in flight, so their four wings look like just two. The legs are basically like that of other insects, having a coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, and tarsus. Each hind leg has a polished cavity in it surrounded by hairs. It’s called a pollen basket, and it does, indeed, carry pollen, which the bee packs into it.

Abdomen

The bee’s abdomen has a projection at the tip that’s known to make people of all ages flee! The stinger! It’s attached to a sac of venom, and the bees use it when they think they’re under attack. Stinging means certain death to the bee because the tip is barbed like a fishing hook and gets stuck in the victim. When the bee flies away, the stinger gets yanked out of her and causes a fatal wound.

Senses

Honeybees have five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch.

Sight

It was already known that honeybees saw light and had distance vision when, in 1919, German-Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch discovered they had color vision, too. Moreover, in a series of tests, he showed that bees could be taught to discriminate between two divergent paths leading to food by following the correct color markings. And they retained a memory of the learned color.

Their visual specialty, though, is seeing colors in the ultraviolet (UV) range. The importance of UV sight is that it uncovers colors and patterns that draw them to nectar sources. Scientists call their ability to see both visible and UV light “bee purple.”

Hearing, taste, touch, communication

They hear by detecting the movements of air particles like, say, those of a bee that’s dancing nearby. (By comparison, humans hear through the detection of pressure oscillations.) Taste sensors are located in hairs on the last segment of their antennae, on their mouthparts, and on the feet of their forelegs. They can distinguish between sweet, sour, bitter, and salt. They communicate through touch during bee dances, and their sensitive antennae can gauge width and depth when constructing cells in their honeycomb. Bees communicate, too, with pheromones, which are chemical signals. Pheromones warn of predators, help drones attract other males to mating sites, distinguish queens-to-be from other larvae, and mark their footsteps.

Bee stings and the human body’s response

Bee venom contains peptides and enzymes that destroy fats that line cells, as well as immune system cells in the skin. When a person is stung, the body releases histamine, which incites blood vessels to dilate so that other immune cells can reach the injection site as fast as possible to neutralize the venom.

For most people, a bee sting causes sharp burning pain, a red welt, a small white spot where the stinger punctured the skin, and slight swelling. The reaction goes away in a few hours. A few unfortunates are allergic to the stings, and their body releases too much histamine. In their case, the blood vessel dilation is extreme and leads to a cascade of life-threatening reactions—as blood pressure drops, cells stop receiving oxygen, and swelling and spasms follow. That can lead to death. An injection of epinephrine usually halts the process because it constricts blood vessels.

Behavior

Honeybees are known as social bees because they live in colonies, unlike other bees, such as bumblebees, which are solitary except to mate.

A colony lives in a hive, which gets its start when a single queen uses wax (beeswax) from her wax glands (located in the lower part of her abdomen) to construct a series of tightly packed cells (honeycomb) in which to lay her eggs. She alone tends to her first brood. From then on, her sole role is to lay eggs, while her female offspring take over all duties of the hive. They add more and more cells, as needed, for raising broods, as well as for the storage of honey and pollen.

Over time, a hive may become overcrowded and need to be divided, so the colony starts a new queen by raising a bee on food called royal jelly. Royal jelly is water that contains protein, sugars, fatty acids, trace amounts of minerals and vitamins, and an antibiotic component. It’s produced by glands within the hypopharynx (located in the head) of worker bees. (Health food stores sell royal jelly for its anti-inflammatory and other health benefits.) A single protein called royalactin seems to be responsible for developing a bee larva into a queen. The old queen leaves the hive, taking with her about half her colony, and the new queen will fill her vacancy.

Each bee plays a role, or many

The queen is the only female in a hive with mature reproductive organs. She’s always the largest bee in a hive, much larger than the others, and she has shorter wings. Also, she lacks pollen baskets. Her sole role is to lay eggs for the duration of her life, which is two to five years. She is capable of grooming and feeding herself but is usually tended by workers.

Workers, the smallest bees in a hive and always females, have a shorter abdomen and pollen baskets on their hind legs. They lack developed ovaries and can’t lay eggs. Working as a team, they perform all the work in the colony. Their duties include feeding and caring for larvae and the queen, adding to the honeycomb, removing dead bees, waste, and debris from the hive, collecting nectar, pollen, resins, and water, producing beeswax, and defending the hive. Their tasks change as they age and upon the needs of the colony. Drones are all male bees. Bigger than workers, they have stout bodies, and their eyes are larger than those of the queen and workers. Their sole purpose is to mate with a queen

Depending upon the age of a hive and the time of year, it may contain 20,000 to 60,000 workers. Spring and summer bees live only a few weeks, having pretty much worked themselves to death. Those born in late summer will live through the winter.

Reproduction

Honeybees develop through a process called complete metamorphosis. They begin as eggs, hatch as larvae, then pupate, and finally emerge as fully grown adults. Each stage looks different from the one before.

Mating is a once-in-a-lifetime event for a queen honeybee. She leaves her hive to mate only once, typically within the first one to two weeks after she emerges as an adult. During this period, she will take several mating flights. During these flights, she flies to areas where males congregate and mates up to ten to twenty times or more.

She stores the sperm she collects in an organ called the spermatheca. This stored sperm is sufficient to fertilize eggs for several years, allowing the queen to lay fertilized (female worker and potential queen) and unfertilized (male drone) eggs as needed.

Drones’ vital, but sadly short, lives

The life of a male is short—he’ll die after mating because his sex organ (endophallus) remains inside the queen when he pulls away, leaving him grievously wounded. “Unlucky” males, those that fail to mate, have it easier for a time. With bodies still intact, they might stay in their hives through spring and summer, eating the nectar there and, often, tended by the workers.

But they’re a drain on resources, consuming about three times as much as workers, so as nectar sources become scarce in the fall, their luck runs out. They’re physically pushed out of the hive and die from starvation because they lack foraging ability, from exposure to cold temperatures, or predators.

Italian Honeybees, Apis mellifera ligustica. The queen is in the very center, depositing an egg in a cell. (USDA; CC BY 2.0)

The queen plays her role

After mating, the queen lays a single egg in each of the brooding cells that were built beforehand by her workers. She controls whether to use some of the stored sperm to fertilize an egg as it passes through her vagina. If she does, the egg develops into a female. Unfertilized eggs become males. Workers play a role in “informing” the queen as to when and to what degree her services are needed. It’s estimated that workers make 110,000 visits to each egg during its egg and larval stages.

Sources vary as to how many eggs a queen lays. The number is somewhere between 1,000 and 3,000 eggs a day, and up to a million in her lifetime! Fortunately for her, there are some restful times when the queen lays no eggs or fewer eggs, such as in the winter.

Eggs hatch in three days. Larvae resemble pearly-white, shiny grubs curled in the shape of a “C” at the bottom of their cell. As they grow, they stretch out length-wise and eventually fill their cell, molting (shedding skin) several times as they outgrow their skin.

Caring for the larvae

The youngest workers take care of the larvae, feeding them royal jelly for the first two days. After that, they feed them pollen or “bee bread,” a mixture of pollen and nectar. After nine or ten days, workers cap the brood cells with beeswax. The larvae then spin cocoons for themselves from silk glands located in their mouthparts and begin to pupate. Full development time from egg to adult varies according to a bee’s caste. It takes queens about sixteen days, workers twenty-one, and drones twenty-four days.

When an existing queen begins to fail or slow down with age, goes missing from the hive, or flies off with part of her colony (swarming), workers start raising a new one. They select several female larvae, apparently picked at random, to feed only royal jelly, which spurs them to develop differently from all other females. (For the curious: feeding royal jelly to a male larva would not alter its genetic destiny to become a drone.) After emerging as adults, new queens fight to the death until there’s just one. They’re able to kill each other by repeated stinging—unlike workers, their stingers have an ineffectual barb that doesn’t get hooked, so queens can sting repeatedly without injuring themselves.

Swarming

Swarming is the way honeybee colonies separate. It usually occurs in the spring and when a queen is about two years old. A queen swarms by leaving her hive with about 50 to 60 percent of her workers to start a new hive. That can mean 25,000 to 30,000 bees flying en masse! (Rarely, there’ll be successive swarms for some reason that nearly empty a hive.)

Before this happens, the queen and her workers do some preparation: The queen lays a few eggs to leave behind for her workers to start raising as new queens. After that, she stops laying, and workers stop feeding her to decrease her weight—she’ll have to fly a long distance with a body heavy with sperm.

Queen bravely makes her move

Before the new queens emerge from pupation, the old queen and her followers leave the hive for good. They fly to a spot, often only a few yards away from their old hive, and cluster together while several dozen scouts, the most experienced foragers, go in search of a new location. Usually, this is only a short wait, a few hours at most, because they’re outside in full view of predators, the queen may be attacked and die, or the weather could turn bad and destroy the entire swarm. They’d also starve to death in about three days without a new source of nectar.

The scouts return with their recommendations based on several necessities: sufficient size, available nectar, protection from the elements and other insects, warmth, and perhaps other factors, too. Each scout conveys the distance and direction to the site she has found, usually a cavity of some sort, by “dancing”—the keener she is about her find, the more excited her steps. The scouts “discuss” in this manner until they reach a consensus on a site, and the swarm follows them to their new location.

Honeybee dances

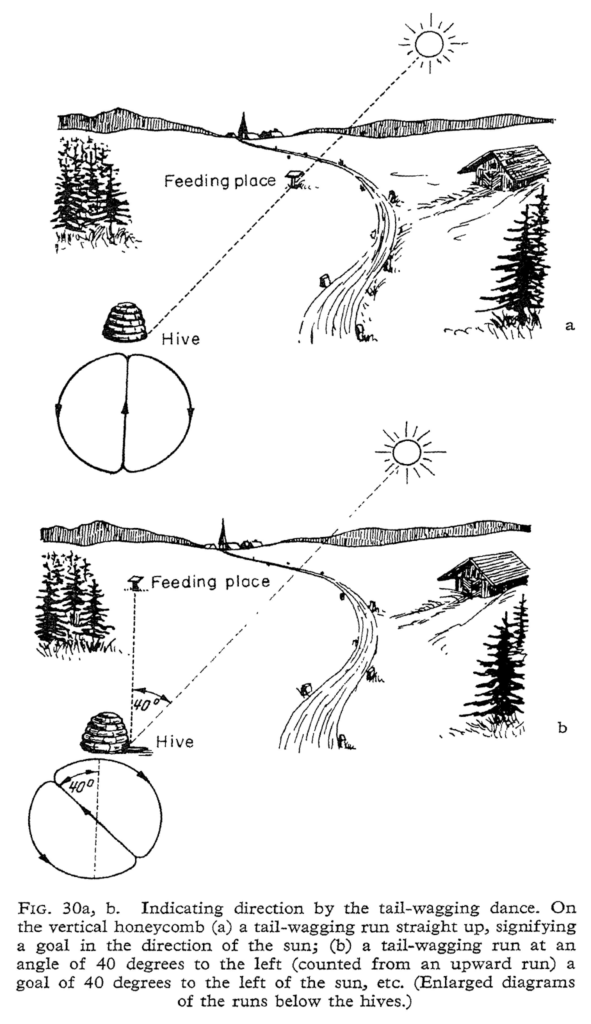

Honeybees perform extraordinary dances as a means of communication regarding food sources. Karl von Frisch interpreted the dances in 1923 while studying the sensory perception of the honeybee.3

How the waggle dance conveys information. (from Erinnerungen eines Biologen, by Karl von Frisch, 1957; PD)

Waggle dance:

A forager arrives at the dance floor (located near the entrance to the hive) and performs a figure-eight pattern while fluttering her wings and shaking her abdomen. Her movements convey direction and distance from the hive and richness of the source. How? Her body, in relation to the sun, shows the direction, and the length of time she performs the dance (in milliseconds) conveys distance. The vigor of her dance indicates the richness of the source.

Tremble dance:

A worker moves about the hive while quivering her legs. This dance communicates that there’s too much nectar in the hive, and foragers need to stop gathering for a time and help process it.

Round dance:

A forager arrives at the dance floor, runs around in narrow circles, and then quickly reverses direction. She’s indicating that food is close to the hive, but it doesn’t convey the direction.

Shake dance:

A forager moves throughout the hive and shakes her abdomen in front of non-foragers to signal them to move to the dance floor. This is performed by a forager when the nectar source she has found is particularly good, and more foragers are needed.

Sickle dance:

A forager performs a crescent-shaped dance to convey that food is located 150–500 feet (50–150 m) from the hive, but it doesn’t indicate the direction.

Food Sources

Foraging workers drink nectar and collect pollen from flowers to take back to the hive. Nectar is a liquid that’s rich in sugar and provides energy. Pollen is a coarse powder that’s protein-rich and contains the plant’s male sperm cells. While moving around plants, the hairs on a bee’s body both trap (with static electricity) and release (rub off) pollen. The pollen fertilizes the female plant parts it touches. Honeybees travel in a 2 to 3-mile radius in their search for food.

Honeybee with pollen on her body and a packed pollen basket (Muhammad Mahdi Karim / Flickr; CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Bees must keep pollen from blowing away as they fly. To prevent that, they mix it with nectar and salivary secretions and pack it into a corbicula, or “pollen basket.” That’s a cavity in each hind leg surrounded by an arrangement of dense hairs that trap and tightly hold the moist pollen. The composition of pollen varies depending on the plant. Back at the hive, it’s passed to other workers who use their heads to pack it into cells.

Predators and defenses

Honeybees face many predators as they go about their busy lives. Bears love to raid beehives to steal their honey. Bees fall prey to carnivorous insects waiting to ambush them as they collect nectar and pollen. They get caught in spider webs. Also, small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and birds eat them.

Honeybees defend themselves by flying away or stinging, which they won’t do unless necessary. A group of bees stinging a predator may drive it away or even kill it. Bees marshal their forces when their hive is attacked. At least one study suggests they have different attack strategies depending on the kind of predator.4

Lifespan

Queens live for two to five years. Females live only a few weeks, except those born in late summer, who live through the winter in their hive. Most males die soon after mating.

| 1 Canadian Honey Council |

| 2 Source: California Institute of Technology, which has conducted research on bee flight |

| 3 There are a few researchers who disagree and believe that dances are performed only to attract attention so that “odor plume” information can be conveyed, which leads bees to nectar. In 1973, along with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz, von Frische received the Nobel Prize for his work in animal social behavior. |

| 4 “Self-organized defensive behavior in honeybees,” PMC/PNAS |