Snails are number two on the list of most species on Earth, second only to insects. Some live in water and others on land. The ones you see in your garden are, of course, land snails. We first notice their shell, although there are shell-less snails called slugs, and you might be all too familiar with those, too. Slugs can be particularly destructive to plants, but snails overall are beneficial because they feed on dead and dying plant material, and their feces are a nutrient-rich fertilizer for the soil.

Snails are also important as food for other wildlife, including mammals, birds, reptiles, and insects. Humans eat them, too: the Roman Snail, Helix pomatia, is called escargot (ess-KAR-go) on the menus of fine restaurants around the world.

The Roman Snail, Helix pomatia, is called “escargot” on restaurant menus. (Waugsberg / Wiki; CC BY-SA 3.0)

Background

Snails belong to a group of highly varied animals called mollusks (phylum Mollusca), including clams, mussels, and oysters. The first snail-like mollusk lived on the seafloor during the late Cambrian Period about 550 million years ago, and then during the Middle Permian Period, around 286 million years ago, some moved onto land and began breathing with lungs instead of gills. Land snails found terrestrial life to their liking and now live just about everywhere, from deserts to tropics, from sea level to mountaintops, and in all parts of the world except Antarctica.

Around the world, there are about forty thousand species of snails living on land, in freshwater, and salty seas. About 725 species of land snails and 40 species of slugs inhabit North America.

Size

The size of a snail’s shell doesn’t necessarily reflect its occupant. Some species have a shell large enough to hide entirely within it, while others have one too small. A drawback for all land snails is that their size is limited by the effects of gravity and their bodily strength. Unlike water snails, which have buoyancy to lighten their load, land snails must bear the full weight of their shell. And what a difference that makes:

The largest sea snail, the giant Australian Trumpet, Syrinx aruanus, can be as long as 3.0 feet (91 cm). But, the biggest land snail, thought to be the African Giant Snail, Achatina achatina, has a shell that measures only 7.0 inches (18 cm). Slugs are limited in size, too, with the largest believed to be the Pacific Banana Slug, Ariolimax columbianus, just under 10.0 inches (25 cm) in length.

At the other end of the snail scale is the world’s smallest, Angustopila psammion, which was discovered in 2022. It has a shell height of 0.02 inches (0.48 mm)—so minuscule you could fit five of them inside a grain of sand! Another tiny snail worth noting is Partula rosea, no more than 0.5 inches (12.7 mm). Native to the Pacific Islands, it’s now extinct in the wild, and half the world’s population of them—about one hundred—now live in a protective habitat in a British zoo.

The shell

Some shells are sporty, with bands of color, like the Cuban Painted Snails, Polymita picta, that defy anyone to pass by without stopping to admire their beauty. Most snails, though, lay low, with camouflaging shades of white, gray, brown, or amber to hide better in whatever terrestrial environment they inhabit.

The natural color variations of Cuban Painted snails, Polymita picta (© Mark Brandon / Shutterstock)

Other distinguishing variables on shells also help identify their species—height and width, number of whorls and ridges, and whether they’re thick or thin. Shells are usually hairless, but some species, mainly as juveniles, have a little bit; it’s thought this helps them cling to wet leaves.

Slugs vary, too, but since they’re essentially shell-less, it’s harder to discern their differences. It often takes an expert’s close examination of tiny features to distinguish one species from another. While most are very dull, a few make a dramatic statement, such as the Banana Slug, Ariolimax columbianus.

The shell consists of three layers:

- Hypostracum (hi-POS-truh-cum), the membraneous innermost layer.

- Ostracum, the middle layer, which consists mainly of calcium carbonate.

- Periostracum, the skin, a mix of proteins that hold the shell’s color. After a snail dies, this layer erodes, exposing the underlying calcium carbonate’s white or gray color.

The shell has its beginning during embryonic development, but it isn’t a living thing. It grows layer-by-layer as cells located on the lip of the aperture (the shell’s opening) release a calcium carbonate material. A liquid, at first, it gradually hardens. Calcium is so essential for development that a diet deficient in it will produce a thin, cracked shell; if this persists, it can be fatal. (Owners of pet snails provide calcium-rich cuttlebone for them to feed on.) The wall of the shell thickens as it grows. (The shell of many sea snails is nearly unbreakable by the time they reach old age.)

Torsion

During its early stages, the shell undergoes a complicated action known as torsion that curls it into a spiral. Torsion to the right (most common) or left is specific to each species.

To determine whether a shell is coiling right or left, look at the apex, the center point where it begins swirling outward. Right (dextral) spirals will go clockwise toward the shell’s aperture. And conversely, left (sinistral) coiling spirals grow counterclockwise.

Snails can’t release themselves entirely from their shell, but they can move in and out of their aperture. Aquatic snails have a hardened “lid” and can completely close themselves inside. Land snails don’t have one, so, depending on the species, they seal their aperture with a covering of mucus (called an epiphragm) or with part of their foot. They enclose themselves for several reasons: for protection from predators, to escape inclement weather—too hot, too cold, too dry—or to take a rest. They can stay within the shell for long periods if necessary.

Slugs

Depending on the species, slugs either have no shell, a minuscule one at the tail-end of their body, or a tiny internal one. There are basically no other differences between a slug and a snail with a shell.

Slugs are long, muscular, and slimy. They’re commonly black or dark brown and 0.5–2.0 inches long (13–51 mm). They’re more prone to desiccation because they lack the moisture retention a shell would provide.

Slime

Snails produce slime, which is a mucus that has different purposes. They use it for movement, to isolate the body from dirt and germs, and for moisture so they don’t desiccate. It’s made of a gel that can change its density from a solid to near-liquid. So, it can be thin for easy gliding across a smooth surface or thick to protect from a rough one. Some slugs can produce a cord of mucus on which to lower themselves. You may have noticed the shiny slime trail left by snails on sidewalks, flowerpots, or even window glass.

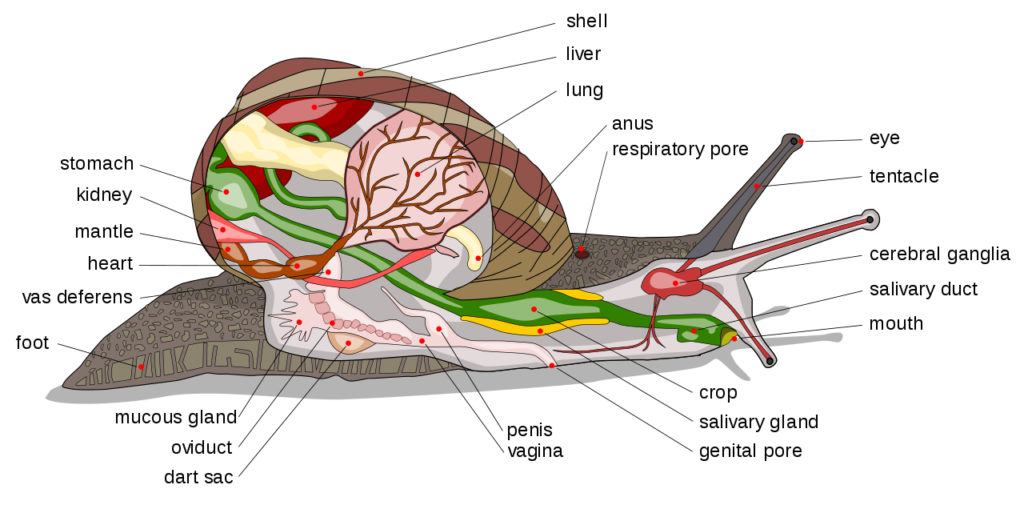

Snail’s body

A snail’s body is soft and, like an earthworm’s, lacks a spine or other bones. It’s divided into three parts:

- Head

- Foot

- Visceral mass (digestive, excretory, and reproductive organs all mixed with no divider between them).

Head

The mouth contains a unique tongue called the radula (RAD-joo-luh), which has rows of incredibly hard, course “teeth” made of chitin. They’re the strongest natural material on earth. They’re five times stronger than spider silk and nearly as strong as the toughest manufactured materials. To eat, the snail draws its rasp-like tongue over food, scraping bits of it into its mouth. It’s used the same way on soft stones, such as limestone, to consume the calcium needed for building the shell. All this scraping wears the tip of the tongue away, but the radula grows from the base throughout the snail’s life, just like our fingernails do. Snails don’t bite, but if you allow one to crawl on your hand, it might “taste” you with its tongue, and you’ll feel its raspy teeth. Don’t worry! It’s painless and feels like a cat’s tongue.

Tentacles and eyes

The tentacles are extremely important. Most land snails have two pairs.

One pair, which sits higher than the other, is longer and has eyes at the tip that look like nothing more than a shiny black dot on each tentacle. (They’re at the base in sea snails). Tentacles can be moved back and forth and up and down to get a better view. They can’t focus, however, so their vision is fuzzy and mainly distinguishes between light and dark.

The shorter tentacles hold chemoreceptors that can taste and smell. They’re usually held lower and used for touching and feeling the immediate environment. At a hint of danger, snails quickly withdraw all four tentacles. Muscles play a role in that, but blood pressure is what extends them.

Visceral mass (internal organs)

The visceral mass is the term for all the snail’s internal organs. They’re covered by the “mantle,” a muscular, skin-like organ that lines the shell’s inside and secretes calcium carbonate for shell-building.

Land snails need only one lung for breathing. Muscles in the mantle expand and compress the lung, drawing air in and driving carbon out through the pneumostome opening. Located on the right side of the body, it can be opened and closed at will. Between breaths, it’s kept closed to hold moisture in.

This is the foot of the Garden Snail, Cornu aspersum, clinging to a plant stem. Note the hole, which is the pneumostome. (Sean Mack / Wiki; CC BY 3.0)

Foot, movement

A muscular organ called the “foot,” located on the underside of the body, moves a snail forward but never backward. They also will use their foot to try to right themselves if they get overturned (often unsuccessfully). Large, flat, smooth, and very maneuverable, it pushes against a surface with a wave-like motion. You may wonder if snails ever move faster than a “snail’s pace?” The answer is no, but some of the larger land snails virtually gallop by snail standards by creating huge waves in their foot. The fastest in the world is thought to be the Garden Snail, Cornu aspersum (formerly Helix aspersa), shown above. At its speediest on a nice, smooth surface, it travels about 6.0 or 7.0 inches per minute (1.8–2.1 m)!

To help them move, snails prepare the surface by secreting a thin layer of mucus from a gland at the front of their foot. The mucus serves several purposes. It reduces friction, produces a suction that helps them cling to things, even upside down (if you’ve ever tried to pick one up, you’ve experienced this resistance), and provides a protective layer that’s so effective snails can climb over sharp surfaces, including a razor’s edge, without injury.

Reproduction

Early summer is courtship time. Land snails are hermaphrodites (her-MOFF-row-dytes), meaning their bodies contain both male and female sex organs. They mate by aligning their bodies so that the penis (yes, they have one) of each is inserted into the vagina (that, too) of the other. Mating may go on for several hours. After they exchange sperm, each stores it in a special pouch and uses it to fertilize its eggs, sometimes over several months. Before all this, though, there’s a courtship ritual. They caress each other with their tentacles, nibble at lips, and rock their bodies back and forth. It goes on for hours before mating commences. It seems, well, rather sweet and romantic.

But not so fast! With a few species, there’s a shocking twist: each pierces the body of the other with a long, sharp spear called a “love dart.” Whoa! That sure changes the mood and begs the question, “Why?” Despite our shocked reaction to this, theirs is to get it on! It apparently stimulates them.

So, do they mind getting harpooned? Well, yes, yes, they do! Snails are capable of feeling pain, and it hurts. They frequently will jostle to stab but not be stabbed. For a relieved 30 percent of them, the other’s love dart misses or fails to penetrate.

Love dart

A love dart is more than sadomasochistic foreplay, however. It prevents a catastrophe because more than 99 percent of the sperm exchanged by the snails gets digested internally before finding its way to the safety of the storage pouch. So, the number of fertilized eggs is significantly less than the initial number of sperm introduced. The love dart is nature’s extreme solution: it transfers a mucus that seems to prevent the snail’s body from digesting too much semen.

Land snails may lay their eggs singly or in clusters of dozens, depending on the species. They might bury their eggs in soft, moist soil by digging down with their foot or hide them in damp, protected places like leaf litter and under logs.

Eggs hatch in about two to four weeks, depending on the species and favorable weather (they don’t hatch until conditions are right). As soon as they hatch, the hungry young snails begin feeding on their calcium-rich eggshell and, sometimes, on the eggshell of other snails, even if it is still unhatched! At this stage, the snails’ shells are transparent and have only one whorl, but over the next few weeks, they slowly take on color. In about three months, they’ll have adult coloration. Snails reach adult size and sexual maturity in two to three years.

Behavior

Land snails are usually active at night when humidity is high, but they may come out in the daytime when it rains to do some foraging. If conditions get too dry, they estivate (a stage of “sleep” not quite as deep as hibernation) and stay that way until it rains. In winter, many species hibernate, during which their heart slows down from about thirty-six beats per minute to only three or four, and oxygen use is reduced to one-fiftieth of normal. Land snails also take naps like humans might do. Research1 on the Great Pond Snail, Lymnaea stagnalis, in 2011 showed they slept off and on for about 22 minutes over a 13- to 15-day period, then stayed awake for the following thirty-three to forty-one hours. During their awake time, they were continuously active.

How did the researchers know the snails were sleeping? Because they were unresponsive to food or when their shells were tapped, their shells hung loosely away from their bodies, and their foot, antennae, and mantle were relaxed.

Epiphragm sealing the opening of a hibernating Roman Snail, Helix pomatia (Hannes Grobe / Wiki; CC BY-SA 2.5)

Whether they’re estivating, hibernating, or maybe just sleeping, snails seal their aperture with an epiphragm, a layer of dried mucus. The epiphragm is usually transparent and sometimes “glues” the snail to a surface, such as a shady wall, rock, or tree branch. In temperate climates, some slugs hibernate underground in winter, but adults of other species die.

Snails spend their active time searching for food, eating, and finding mates, but they’re otherwise not social. They may be seen hiding in groups, but they don’t communicate other than to follow snail trails to find a mate or, for the few carnivorous species, to find prey.

Habitat

Typically, snails live where they can find moisture and darkness, although a few hardy species live in semi-arid regions. They survive when weather conditions are dry (which is most of the time) by burying themselves in soil, withdrawing into their shell, and plugging the aperture to conserve moisture. After that, they estivate until it rains. When rain does come, there’s a rush of activity—they must eat, mate, and lay eggs before the environment dries up again.

Most snails live in marshes, woodlands, pond margins, flower and vegetable gardens, leaf piles, mulch, rocks, logs, cracks and crevices, flowerpots, and other yard fixtures. Unencumbered by a shell, slugs can squeeze into places the others can’t.

Typically, snails stay within a small range, but environmental disturbances can easily affect them. They’ll disperse to new areas, if possible, but since they can’t do it quickly, they may not escape a dangerous change. Primarily, snails are relocated through flooding and streams. Also, humans distribute them in soil or pots of flowers purchased at a garden center. Some have been found attached to the fur of an animal. It’s conceivable that the wind might sweep up tiny snail eggs.

Food sources

Land snails take advantage of whatever food they find within crawling distance, and there’s a lot of variety in what they eat. The majority are herbivorous and graze on plants, fungi, and algae. A few New Zealand species are carnivorous and feed on other snails and nematodes (tiny worms).

Snails also eat empty snail shells, sap, animal droppings, and even inorganic stuff, such as limestone and cement (for the calcium content).

Lifespan

The lifespan of land snails depends on the species. Heavy predation by beetles, birds, and other animals means most don’t make it through their first year. Many of them are eaten as eggs. Those that do make it live around two or three years. Captive snails have lived ten to fifteen years or more. Land snails have the highest number of extinct species worldwide, with many more threatened due to invasive predators, habitat loss, and climate change.

Predators

Predators take a considerable toll. They include mammals, such as rats, moles, badgers, and humans, as well as birds, toads, frogs, crabs, turtles, beetles, and ants. A species goes extinct; “Lonely George,” the last of his kind

1 Eric Schwitzgebel, “Is There Something It’s Like to Be a Garden Snail?, December 23, 2020, https://bit.ly/44ODO1b.

2 Richard Stephenson, Vern Lewis, “Behavioural evidence for a sleep-like quiescent state in a pulmonate mollusc, Lymnaea stagnalis (Linnaeus),” Journal of Experimental Biology, Volume 214, Issue 5, March 2011, https://bit.ly/3DU2HwF.

More reading

All about earthworms

Did you know this about frogs and toads?

All about box turtles