A certain large band of insects has earned itself a notorious reputation. First off, they buzzzzz all around our picnics and patio parties. They lap the ice cream, dive into cola, and tickle through the little hairs on our arms. Sometimes, they bite, too. Indoors, they behave no better. And they also may carry diseases. So you can hardly be faulted for wishing all flies could be driven from the planet. Particularly since insect expert Erica McAlister1 reports there are an estimated seventeen million flies in the world—that’s per person! The good news is that the vast majority of them go unnoticed as they quietly do important work for our planet.

Jump down to: Background • Physical description • Head, Brain, Eyes, Antennae, Mouth • Thorax, Wings, Legs • Abdomen • Senses • Reproduction, Life cycle, Lifespan • Behavior, Habitat, Diet, Predators • Flies and disease

Importance of flies

Flies are second only to bees and a few wasps as pollinators of plants. In some cases, they’re the primary pollinators. For instance, the world would have no chocolate without midge flies to pollinate cacao flowers!2 Flies are also recyclers of plant and animal matter into organic nutrients. Entomologist Brian Lessard says, “. . . if we lived in a world without flies, our streets and parks would be full of dead animals, rotting leaves and logs and nasty surprises left by dogs.”3 As if that wasn’t important enough, flies are predators of undesirable insects and themselves food for other wildlife.

In the following, you’ll read about their abilities, behavior, and much more. For instance, did you know they can fly both forward and backward, hover, and turn on a dime? Have you seen them flip upside down to cling to your ceiling and wondered how they did that? You’ll find the answers here. You’ll also find that not all flies are House Flies and horse flies. Flies are diverse in appearance, with several species resembling bees and wasps.

Background

Flies first appeared on Earth over 200 million years ago during the Upper Triassic Period. Today, they live everywhere except the Polar Regions and are among the most successful insects on our planet. More than 120,000 fly species have been identified so far. They include robber flies, crane flies, flower flies, soldier flies, and fruit flies. Mosquitoes, gnats, and midges are flies, too. More than 16,000 species make their home in North America. About 91 percent of all flies living around human habitations are House Flies, Musca domestic, because the smell of our food and garbage attracts them.

From scary-big to nearly invisible

The world’s smallest fly is Euryplatea nanaknihali, discovered in Thailand in 2012. It measures a minuscule 0.0158 of an inch (0.4 mm). At the other extreme is the giant Mydas Fly, Gauromydas heroes, one of about 471 species in the family Mydidae. It’s 2.8 inches (70 mm) long and inhabits Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay. The largest one in N.A. is the Clubbed Mydas Fly, Mydas clavatus, 1.0 to 1.2 inches (25–30 mm) long, with a wingspan of up to 1.7 inches (50 mm) or more. The smallest fly in N.A. is likely Euryplatea nanaknihali, a member of the family Phoridae. It measures only about 0.02 inches (0.4 m) in length. Discovered relatively recently, it holds the record for the smallest fly species in the world.

Flies belong to the order Diptera (DIP-ter-uh), a word from the Greek dipteros for “two wings.” As the name says, they have only two wings, which sets them apart from almost all other flying insects. Dipterans are considered “true flies” because there are other insects with the word “fly” in their name but aren’t actually flies. Think of butterfly and dragonfly—they aren’t flies.4

Suborders

Diptera is divided into two suborders. The first is Nematocera (nee-maw-toe-SER-a), a word from New Latin nemat + cera, for thread-like horn. It consists of primarily aquatic flies, such as mosquitoes, crane flies, and midges, all of which are delicate-bodied, slender, usually small, and have long antennae with at least six segments. The second suborder, Brachycera (bra-KISS-err-uh)—from New Latin brachy + cera, for “shortened horn”—consists of heavier-bodied flies with antennae of usually no more than three segments.

Physical description

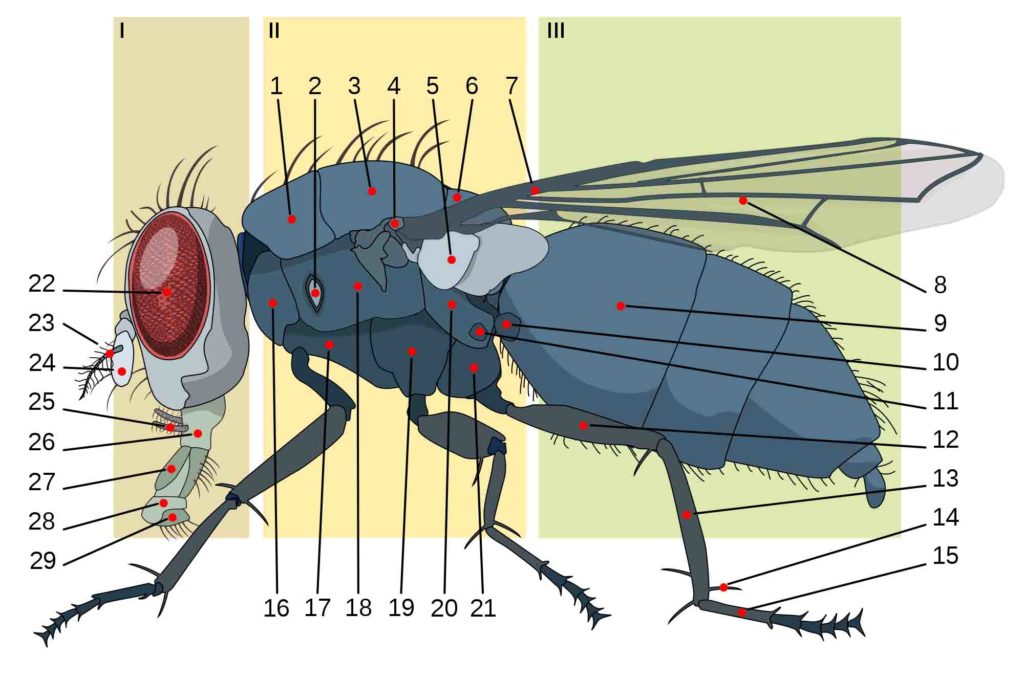

A fly has three body sections: head, thorax, and abdomen. Its shape is typically slender, with long legs. An external skeleton (exoskeleton) made of chitin, which is tough and flexible, encases the body to provide support and protection. There are bristles and hairs on the body; some flies have more than others.

Most are a shade of brown, gray, or black. There are some pale ones, though, and bright ones, too. For example, those in the family Bombyliidae (bom-buh-LIE-uh-dee) look much like bees. Flower flies have striking black-and-yellow patterns on their abdomen. Long-legged flies, in the family Dolichopodidae (doll-uh-co-PODE-uh-dee), are iridescent green or orange.

Fly external anatomy. I: head; II: thorax III: abdomen. — 1: prescutum 2: anterior spiracle 3: scutum 4: basicosta 5: calypters 6: scutellum 7: wing vein 8: wing 9: abdominal segment 10: haltere 11: posterior spiracle 12: femur 13: tibia 14: spur 15: tarsus 16: propleuron 17: prosternum 18: mesopleuron 19: mesosternum 20: metapleuron 21: metasternum 22: compound eye 23: arista 24: antenna 25: maxillary palps 26: labium 27: labellum 28: pseudotracheae 29: tip. (Fiestoforo / Wiki; CC BY 4.0)

Head

The fly’s head is large and movable. It contains a brain, two compound eyes, three simple eyes (usually), two antennae, and mouthparts. Parasitic flies, Ormia ochracea, also have unique hearing organs they use to locate singing prey, such as crickets.

Brain

The brain contains only 100,000 neurons, compared to 100 billion for humans. Despite that limitation, it has strong systems for detecting and remembering smells. They can also make decisions and appear to “think” before acting.

Eyes

Two compound eyes occupy most of the head. Together, they have an almost 360-degree field of view and can see colors. The eyes are composed of up to 3,000 or more individual lenses (called ommatidia) and are sensitive to any movement around them. Most species also have three simple eyes, or ocelli, arranged in a triangular pattern on their “forehead.” These sense light rather than images. Some flies have eyes that reflect dazzling colors. Those of blowflies and fruit flies, for example, reflect red, a horse fly’s eyes reflect bold metallic colors, and the Deer Fly Chrysops relictus has gold-green eyes with dark-red patches.

Antennae

Flies have two antennae covered by sensory organs for detecting odors. Depending on the species, they may be long or short. Those with long antennae tend to be small and delicate, and many of them produce aquatic larvae. They include mosquitoes, midges, and crane flies, among others, and are grouped in the suborder Nematocera. Those with short antennae tend to be heavier-bodied, but not always, and are in the suborder Brachycera. They include house flies, fruit flies, and blowflies.

Mouthparts

Flies don’t chew; they consume their food in liquid form. All have upper and lower lips (labrum and labium), most have maxillae (“pincers” to hold and manipulate food), two appendages called palpi (sensory organs), and many have mandibles (strong jaws for cutting and sawing).

Robber fly, Asilidae sp. A formidable predator, notice its large compound eyes and needle-like proboscis, used to stab prey and inject a neurotoxin to subdue it. (© guraydere / Shutterstock)

Flies take in their liquid food in one of three ways, depending on the species: by sucking, sponging or lapping, or rasping-sucking. House Flies, for example, sponge up liquids with their labium. Fruit flies stab into fruit with their proboscis and suck the juices. Female deer flies, horse flies, biting midges, and others5 associated with painful bites use rasp-like mandibles to saw through skin and suck up flowing blood (the males suck nectar).

Female mosquitoes stab through skin with a syringe-like proboscis and then suck blood. Robber flies stab prey, inject a combination of venom and digestive enzymes into it (to subdue and liquefy the hapless creature), and then drink the liquid. (That sounds like a pretty awful way to kill something, but robber flies are beneficial as predators of pest insects. Fortunately, they aren’t aggressive toward humans, although they may bite if handled.)

Thorax

The thorax is the fly’s middle section. It’s all about movement because that’s where the wings and legs are attached.

Wings

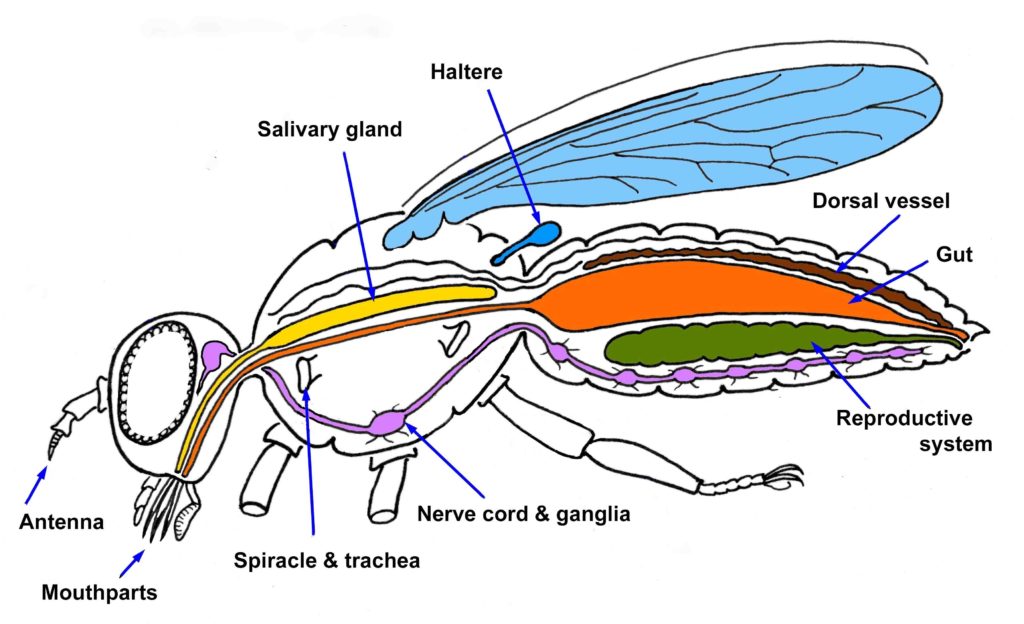

Most insects have four wings, but flies have just two, the front ones. Why the hind wings don’t develop isn’t known, but in their place are tiny club-shaped “halteres” that oscillate with the forewings and behave like gyroscopes to keep the body level. It’s speculated they may also be used in some way when a fly walks.

The forewings are delicate and appear transparent, sometimes with a few markings. However, scientists have discovered that in front of a black background, they glow with rainbow colors on a par with a butterfly’s. Different species have unique patterns of colorful spots, swirls, and stripes, which may be one way they communicate with each other and identify other species. The colors aren’t pigments but a reflection off of the microscopic structures in the wings.

Apparently, flies see their lack of hind wings as a glass half full because they compensate by simply ramping their wing speed up to 1,000 times per second when necessary. That makes them the champion wing-beaters of the world!

Agility

Although they don’t use that adaptation to fly forward particularly fast—top speed is about 5 miles per hour (8 kmh)6—they harness it for a tactical advantage. They can fly in any direction, turn 90 degrees in milliseconds, go forward and backward, hover, and flip upside down to stand on a ceiling. Fruit flies under study were seen to fly nearly upside down, and other species may do it, too. Dario Floreano, who studied insect flight control and how it might apply to robotics7, has this to say about flies’ aerial agility,”. . . (they’re) “arguably the most agile objects on earth, including all things man-made and biological.”

Picture-winged Flies, Chetostoma curvinerve, are fruit flies with a noticeable wing pattern. (gailhampshire / Flickr; CC BY 2.0)

Legs

Flies have six long legs, three on each side, and they’re composed of many human-like structures: hip bone, femur, tibia, and tarsus. Their feet are equipped with tiny claws that play an important role. A particular talent is their ability to walk up walls, cling to window glass, and hang upside down. They manage to do that using large, hairy footpads made up of short hairs called setae (SET-ee). The setae are spatula-shaped and produce a “glue” made of sugars and oils. So how do those six tiny tootsies become unglued when the fly wants to fly? As it happens, each glued foot uses its two claws to help it get unstuck. (With the right equipment, scientists can see the gluey footprints left behind.)

Abdomen

The abdomen is the back section of the body and the largest. Within it are the rearmost parts of the nervous, digestive, and circulatory systems, in addition to the excretory and reproductive systems.

The entire cavity is filled with clear “blood” (called hemolymph) that doesn’t carry oxygen. Instead, flies breathe through a series of sixteen respiratory openings called spiracles, eight spaced along each side of the abdomen. (The thorax has another pair.) Attached to each one is a tube-like trachea that networks throughout the body to passively deliver oxygen to cells and collect carbon dioxide to be expelled.

Flies don’t have a heart or blood vessels. Instead, in what’s called an open circulatory system, blood circulates from the “dorsal vessel,” a pumping organ, to the insect’s head and then freely floods back through the body, bathing all the organs in nutrients and taking up waste along the way.

The digestive system is essentially a long tube that stretches from the mouth to the rectum. It consists of several sections (guts), including a stomach. Nutrients are extracted from food and passed through semi-permeable membranes into the blood-filled body cavity.

Senses

Flies have five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. Their eyesight is excellent, and most also have color vision. Their antennae have hair-like sensory nerve cells that detect odors and sound waves. The maxillary palpi (part of their mouthparts) have taste sensors. They can feel touch through scattered hairs on the body.

Reproduction

Flies undergo complete metamorphosis, which means they progress in four stages, from egg to larva to pupa to adult.

Females announce their sexual willingness by releasing enticing chemical odors (pheromones). Some species have complex courtship rituals. Take fruit flies, for example. A male must follow a sequence of steps to accomplish a seduction. Although the female has released “come hither” pheromones, he must convince her he’s the most suitable suitor. First, he taps her on the abdomen with his foreleg. Then he shows off by “singing” to her by vibrating his wings. His final show of ardor is to touch his mouthparts to her genitals. If these actions don’t take place in the proper order, the poorly organized little guy is plain out of luck.

Mosquito larvae at the surface of water. About one hundred eggs at a time are laid on the surface. (© Ajintai / Shutterstock)

Females lay their eggs in masses of dozens to hundreds in moist places, such as fruits, vegetables, fungi, carrion, manure, and with parasitic species inside their hosts. A single House Fly, Musca domestica, may lay 500 or more eggs in her lifetime, and there may be as many as ten or more generations of House Flies in a season. The eggs hatch in warm weather, anywhere from half a day to weeks later, depending on the species.

Video: Female Picture-winged Fly, Pseudotephritis approximata, depositing eggs in rotting wood. (Katja Schulz / Flickr: cc by 2.0)

Larvae

Fly larvae are usually soft-bodied and legless, and aquatic species have poorly developed heads. Aquatic species breathe through a tube at the tip of the abdomen, raising it above the water’s surface like a snorkel. Most flies are non-aquatic and live in either the soil or decaying matter or are parasites of other wildlife.

Larvae feed nonstop. As they get larger, they outgrow their skin and, depending on the species, shed it (molt) three to eight times. When they’ve molted for the last time, they move away from their food source to pupate within their hardened outer skin or in a cocoon made of soil, silk, or both. When they emerge, they’re fully formed adults and soon ready to start mating.

Lifespan

The lifespan of deer flies and horse flies is two or three years, but only thirty to sixty days of that is spent as an adult. House Flies go through their entire life cycle in about thirty days, spending about twenty-five days as adults. Fruit flies spend a week or two as larvae and pupae, then forty to fifty days as adults. Most flies overwinter as larvae or pupae. Adults usually die, although some survive by hibernating in warm places, including homes or attics, where they may make a surprise winter appearance.

Behavior

There are some exceptions, but most flies are active in the daytime. Many adults go unnoticed, but some can easily be spotted as they go about their daily business. There are those that buzz around flowers, sipping nectar. Others perch on foliage, waiting for prey to pass by. Sometimes, as with mosquitoes, humans are among their game. (It would take only 1,200,000 mosquito bites to totally drain our blood, so be very careful out there!) If Mosquitoes Love You, It’s in Your Genes

Habitat

There’s hardly any environment or organic matter that flies don’t live in or on. The larvae of aquatic species are found in lakes, ponds, rivers, puddles, swamps, marshes, birdbaths—even brackish water. Some larvae burrow into sediment on the bottom, while others live in water-plant stems, leaves, and roots. Non-aquatic species live in soil and fungi, on plants, under bark, in garbage, and in dead or alive animal tissues. Some, the larvae of the Petroleum Fly, Helaeomyia petrolei, live in pools of crude oil, feeding on insects that fall into them.

Food sources

Both male and female adults feed on a wide variety of foods, including nectar, sap, living or decaying plant or animal matter, other insects, and dung. Females of some species, such as mosquitoes, drink blood. Hessian Flies, Mayetiola destructor, eat grass. Some, like crane flies, don’t eat at all as adults.

Golden-backed Snipe Fly, Chrysopilus thoracicus, found in wooded areas of the eastern U.S. Adults are alleged to be predatory. (Katja Schulz/Flickr; CC BY 2.0)

Larvae feed on various foods, both plant and animal, with some being parasitic. The larvae of many species look like white rice—they’re the roiling masses of “maggots” we see feasting on rotting carcasses and garbage.

Predators

Birds, bats, insects, and spiders prey on adult flies, and larvae are prey for fish and other aquatic life.

Flies and diseases

There’s no denying that despite their benefits to the world, flies are disease vectors. Those that feed on garbage and carcasses inadvertently collect disease organisms on their bodies. Pathogens are then transferred to whatever the flies touch or feed on, including our foods. If a fly that landed on a hotdog at a picnic had previously foraged in a dead animal, that’s a potential problem.

Flies can also spread germs to humans when they bite. Fortunately, most people in the U.S. don’t develop symptoms greater than short-lived pain or an itch. We also have accessible medical care should we need it. But, in many parts of the world, fly-transmitted diseases take a tragic toll, causing unimaginable human suffering and millions of deaths each year.

| 1 Curator of Diptera, Museum of Natural History, London, and author of “The Secret Life of Flies,” published in 2017. |

| 2 We have certain species of flies in the family Ceratopogonidae, called Chocolate Midges, to thank for this. They inhabit Central America, South America, Africa, and Asia. |

| 3 Watch his interesting TEDx talk. |

| 4 Curiously, with true flies, the word “fly” is separate from their common name. For example, there are the Bee Killer Fly, Robber Fly, Tabanus Horse Fly, Mosquito Hawk Crane Fly, and House Fly—while, with other insects, “fly” is used to form one word. But the Monarch Butterfly isn’t a butter fly, and the Golden Dun Mayfly isn’t a may fly. |

| 5 Types of flies that bite: deer, horse, black, stable, snipe, sand, yellow, biting midges, and some gnats. Mosquitoes stab rather than bite. |

| 6 A male horse fly, Hybomitra hinei wrighti, was clocked at 90 miles per hour (145 kmh) while pursuing a female, according to Wikipedia.com. |

| 7 Floreano, Dario; Zufferey, Jean-Christophe; Srinivasan, Mandyam V.; Ellington, Charlie, Flying Insects and Robots, Springer Science & Business Media, 2009. |