Poor, lowly earthworms, with nary a thought from us, quietly work magic day and night right under our very feet, but they’re given little respect. Instead, we should be celebrating them as did the ancient Egyptians because earthworms are the champs of soil restoration. Aristotle called them “the intestines of the earth.”

Jump down to: Background • Physical description, Slime • Internal organs • Head, brain, mouth • Senses, Movement • Behavior, Hibernation, Tunneling, Middens • Foods, Habitat • Reproduction • Lifespan, Predators, Threats

Earthworms are the primary force that pulls residue from crops and other plants into the soil, where microorganisms transform it into rich, loamy humus. Worm poo is a potent fertilizer—five times richer in nitrogen, seven times richer in phosphates, and eleven times richer in potassium than the surrounding soil. In addition, their tunnels aerate, which improves drainage and prevents erosion. Taken all together, their labor benefits the food we eat, the flowers we love, and the trees that shade us. Plus, other wildlife gain something because the worms themselves are food. Humans in some parts of the world eat them, too.

Fortunately, we’re entering a sort of earthworm Renaissance where people of all stripes—from farmers of sizable acreage to home gardeners tending a small bed—are coming to recognize that these hidden gems underlie much of Earth’s bounty. In some parts of the world, agricultural areas are even going “no-till” to safeguard them.

Background

Earthworms are ancient. In 2002, Australian researchers found a fossilized trail in sandstone they believe was made by a worm-like animal perhaps 1.2 billion years ago. The fossil is the oldest evidence of the earthworm’s existence and marks it as Earth’s oldest multi-celled animal.Earthworms are animals in the phylum Annelida, along with leeches. The name comes from the Latin anellus for “little ring,” a reference to the many segments of their bodies. Today about 2,700 species are known to exist, and they’re found on every continent except Antarctica. In the United States, there are about one hundred species of native earthworms and another fifteen or so non-natives.

Types of earthworms

Earthworms aren’t all alike and don’t perform the same kind of work or live at the same depth. There are three major groups:

- Surface-soil species: These earthworms live just under the soil surface or within organic matter lying on top. Researchers have found that they’re most numerous in the crowns of grass clumps—the junction where stems and roots meet. They’re shaded there and hidden from birds while they feed on decaying leaves and roots. The grass also offers some protection from high temperatures. This category includes other species that live in the highly rich environment of compost piles and can’t survive in soil containing less organic matter. Typically small, these earthworms have adapted better than other species to extremes of heat, cold, and moisture.

- Upper-soil species: These earthworms live close to the surface but slightly deeper and feed on soil and whatever organic matter it contains. Their tunnels are temporary and become filled with worm droppings, which add nutrients to the subsoil.

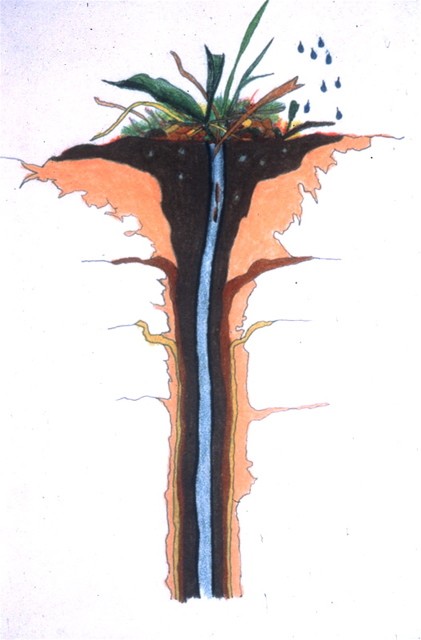

- Deep-burrowing species: Typically called nightcrawlers, they form permanent, vertical tunnels that may go down 8 feet (2.4 m) into the soil. They create middens (more about that later) at the entrance to their tunnels.

Physical description

Earthworms vary widely in size, but most are only a few inches long, and some are less than 1 inch (25.4 mm). There is an outlier, however, the Giant Gippsland Earthworm, Megascolides australis, an endangered (and harmless) Australian species that lives in the subsoil and can grow up to 9.8 feet (3 m) long! That makes the nightcrawler, Lumbricus terrestris, the largest U.S. earthworm, minuscule by comparison, at only 10 inches (25.4 cm).

To most of us, earthworms look pretty much alike. To experts, though, there are many differences. There’s body length, of course, but they also vary in such characteristics as coloration, number of body segments, and type and location of tiny body hairs called setae.

Earthworms range in color from reddish to gray to brown. Their skin, called a cuticle, is soft and permeable. It’s also slimy—so much so that most people are reluctant to touch them.

Slime is prime!

Except for the yuck factor, slime is harmless, and for earthworms, it’s a lifeline. Produced by a thick ring of glandular tissue called the clitellum (kly-TELL-um), it’s a mucus crucial for keeping earthworms moist. There are a few reasons why they must stay moist. First and foremost, they need it for breathing because oxygen enters directly into their bloodstream through tiny pores in their skin after dissolving in the mucus. If an earthworm dries, it dies. Slimy skin also serves as a lubricant to help ease earthworms through the soil. And finally, mucus forms the cocoons that hold earthworm embryos.

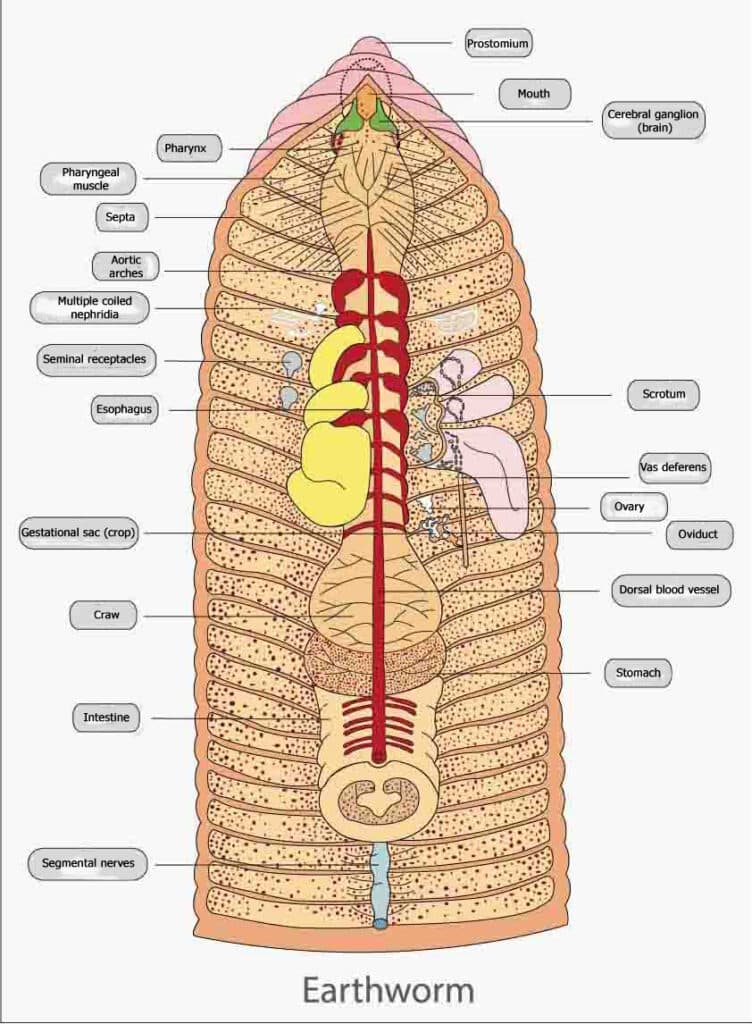

Internal organs

Earthworms have no skeleton. They’re soft, simple animals perfectly formed for the work they do. Their body is basically a muscular cylinder of ring-like segments called annuli (ANN-u-lie), which taper off at both ends. Some species have as many as 150 of them, each coated by mucus. They can slide through the soil like a sled across ice.

The body contains a simple circulatory system with two main blood vessels, five bands of tissue that pump blood, a digestive tract, reproductive organs, and an anus. In addition, they have two heart-like organs, and between them are glands that manage calcium in their diet.

Head

You may have wondered if earthworms have a head and brain. Well, they do! And the head can be identified. It’s called the prostomium and is at the end of the body closest to the clitellum (the band that’s usually a lighter color than the rest of the body). They also have a mouth—it’s toothless but equipped with strong muscles for eating. And, eat they do—up to half or more of their body weight per day.

The front of a Nightcrawler, Allolobophora chlorotica. The mouth is the rounded projection at the very tip. (Gilles San Martin / Flickr; CC BY-SA 2.0)

Brain

As for the brain, research shows it holds a mere 302 neurons and 7,000 synapses.1 By comparison, a fruit fly has 250,000 neurons and ten million synapses. (Neurons transmit sensory input to and from the skin and muscles; synapses are the various connections between nerve cells.) Yet, despite being so rudimentary, another study2 surprisingly shows they can “think” and decide whether to investigate a particularly delicious odor or not.

Mouth, digestion

Earthworms use muscular “lips” and a sucking action to pull food into their mouth. The food is moistened (if it isn’t already wet) and swallowed. Next, it moves down the throat to a storage pouch called a crop. It goes from there to the gizzard, where powerful muscles grind and mix it with a bit of help from fine sand particles that have also been consumed.

When the now-pulverized food moves to the intestines, it’s a thick paste. Most of the earthworm’s body is intestines. As the food moves through that long tube, digestive juices break it down further, and nutrients pass into the bloodstream. What’s left over, mostly revitalized soil, exits the body through the anus.

Earthworm castings are rich in nutrients for plants. They make excellent fertilizer. (Muhammad Mahdi Karim / Wiki; CC BY 2.0)

There’s a name for worm poo: castings. Castings are so rich in nutrients that many people maintain a worm bin into which they throw fruit and veggie scraps, crushed eggshells, coffee grounds, tea leaves, and more. The worms work their magic, and the resulting compost is used in potting soil, as a mulch, or made into a “tea” to sprinkle as fertilizer.

Senses

Having a simple body doesn’t mean they lack senses. Earthworms react to heat, cold, touch, and vibrations and have chemoreceptors that detect odors. They don’t have ears, a nose, or actual eyes, but they have light-detecting cells. The ultraviolet rays in sunlight can kill them, so they always move away from direct light.

Movement

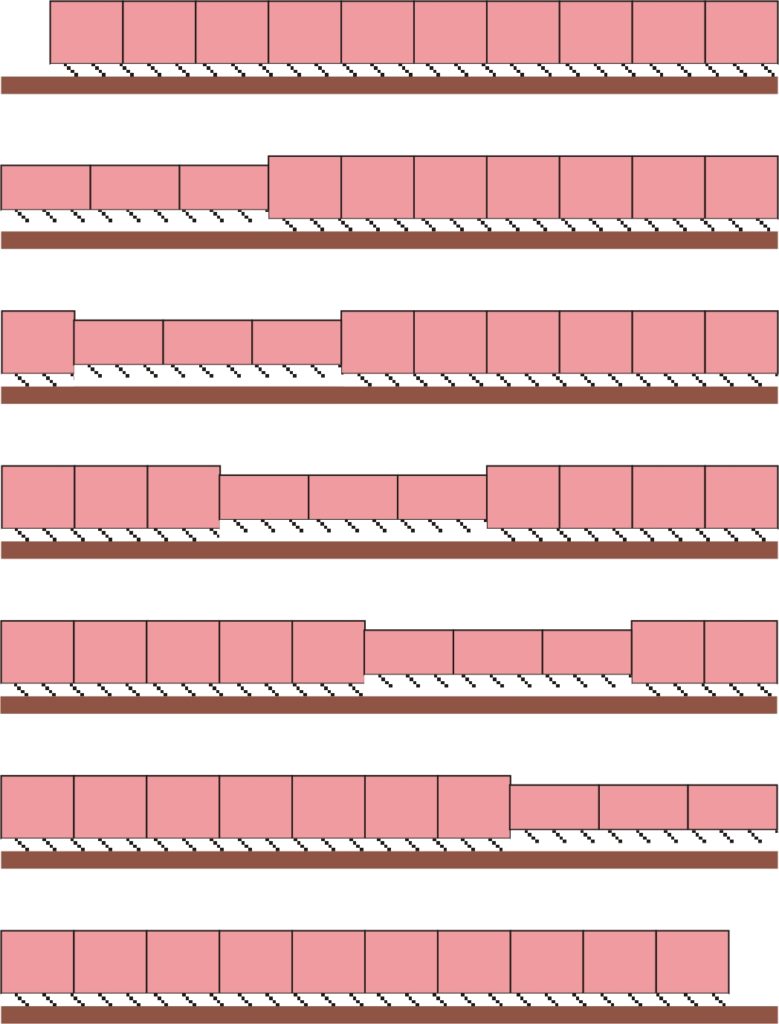

For movement, two different sets of muscles come into play: circular muscles that surround each segment and long muscles that run the length of the body.

Earthworm movement. Each square represents a body segment that’s either in a restricted (horizontal box) or relaxed position. The sequence of movements, assisted by setae, propels the body forward. (Mokele / Wiki; CC BY 3.0)

Assisted by tiny, bristly setae to anchor segments to surfaces as needed, these muscles constrict and release in sequence, propelling the earthworm. They typically move forward (which is one way to tell their head from their rear), but they’re capable of backward movement, too. Video showing earthworm movement

A chop won’t make two

You may have heard that chopping an earthworm in two will produce two worms. That isn’t necessarily so. The front half might live and grow into a full-size body, but only if it has the clitellum and ten body sections behind it. When that happens, new growth will be a little smaller in diameter. The back part always dies.

Behavior

To survive, earthworms need food, oxygen, moisture, a specific temperature range, and no sun. They’re ectothermic (cold-blooded), which means they don’t generate body temperature—it will always be the same as their surrounding environment. Most prefer 50 to 70 degrees F (10 to 21 C), but some species can tolerate a higher or lower range. They live closer to the surface in warm weather to soak in some heat and deeper in winter to avoid freezing.

They’re most active between dusk and dawn. It isn’t known if they sleep during daytime hours, but research4 has shown they use less oxygen, which suggests a lower level of nervous activity.

Tunneling

Earthworms move through tunnels they create. Some go horizontally, some vertically. Either way, tunneling aerates the soil, which allows oxygen and water to penetrate to plant roots and soil microorganisms. They eat soil and decompose plant materials as they burrow. Good soil may hold up to a million earthworms per acre, eating as much as ten tons of leaves and other plant matter per year.

Middens

Middens are piles of worm poo and plant residue. It isn’t precisely clear to experts why worms build middens, but it’s probably to hide their tunnel entrance while providing a handy pile of plant scraps to feed on from underneath, safe from sun and birds. They dissolve over time, and as they do, they fertilize the soil at the top and drain into the tunnels, which also nourishes them. As a result, the grass around a midden is sometimes greener and taller, and you may have noticed that in your yard. In un-tilled soil, tunnels are permanent and used for several years.

Hibernation, estivation

Species that live close to the surface die if freezing weather sets in. Those that move below the frost line enter a state of hibernation, and groups may ball up together to reduce moisture loss. Then, in spring, as the soil warms, they tunnel upward.

If conditions become too dry or too hot for normal activity, earthworms estivate, which is a stage of sleep that’s less deep than hibernation. It’s easy to identify estivating earthworms because they tie themselves up in a knot.

What’s with those stranded earthworms?

Ever taken a walk right after a rain shower and found squiggling earthworms along your path? Why they surface and strand themselves like that is a mystery. What’s known for sure is that they don’t do it to avoid drowning. Edwin Berry, an entomologist with the USDA ARS,5 who studied earthworms for ten years, found they can live for weeks in water. Some experts theorize that rain or high humidity offers them a chance to disperse to new feeding areas, a way to move around “outdoors,” as it were, without drying out. If you see one lying on the pavement, do it a favor: pick it up and place it on the ground in a shady spot, because sunlight paralyzes them after about an hour, leaving them unable to move to safety.

Foods

Earthworms that live close to the surface eat plant matter, dead or alive—decaying roots, leaves, fruits, vegetables, and seeds. Those living deeper mostly eat dirt, which contains fungi, bacteria, nematodes (a class of worms, usually microscopic in size), and other tiny organisms. (Either way, worm excrement contains nutrients beneficial to plants.) Some worms live in compost bins, where they feed on the garbage that gets tossed in.

Habitat

Earthworms live wherever there is darkness, damp soil, and plant matter. Their habitat varies depending on the species, with some living closer to the ground’s surface than others.

Reproduction

Earthworms are hermaphrodites (her-MAFF-row-dites), which means they have both male and female reproductive organs. The male sex organs are in specific segments of their body, and the female organs are in other segments. Despite this, it still takes two worms to tango.

First, they must find each other, and it’s mostly through happenstance, like when they detect ground vibrations or the movement of leaves or grass when another is passing by. When that happens, they feel around until they locate each other. Then, they mate by positioning their bodies so that their heads point in opposite directions, with their sex organs aligned for the transfer of sperm from one earthworm into the sperm receptacle of the other. Their setae hold their slippery bodies together. Following their pairing, they separate and go their own way, both ready to reproduce.

Fertilization

So, okay, they’re now holding sperm they’ve gotten from each other, but how to combine it with the eggs they hold in a separate vesicle? Well, nature has provided a fix for this. The clitellum (a band of mucus that encircles part of the body) secretes a ring of sticky mucus that slides forward, first over the segments containing eggs, which adhere to it, and then over segments containing the sperm, where they get fertilized. The mucus continues its way forward, carrying the fertilized eggs until it slips right off the front of the worm. Both ends seal closed, forming a cocoon that’s left lying on or in the soil.

Depending on the species, earthworms produce between three and eighty cocoons a year. Those that live deeper in the soil produce fewer. Cocoons, at first soft, become hard and leathery and are the size of a grain of rice, but shaped like a lemon. They may hold between one and twenty fertilized eggs.

Depending on the species, the embryonic stage lasts from three weeks to five months. They develop in a way similar to that of a bird in its eggshell by consuming nutritive matter within the egg. Embryos can survive underground until temperature and moisture conditions are just right for hatching. In less-than-optimal situations, they may overwinter and hatch the following spring. Babies become adults in ten to fifty-five weeks. An earthworm without a noticeable clitellum is not yet a sexually mature adult.

Lifespan

Earthworms live from four to eight years, depending on the species.

Predators

Predators include snakes, birds, toads, rodents, moles, foxes, certain beetles, slugs, and humans.

Environmental threats

Intensive use of manure and acidic soil (they prefer neutral) can kill earthworms. Oxygen-depleted soil (such as heavy clay), drought, heavy metals (such as copper), pesticides and other chemicals, and tilling also lead to their death. No-till acreage can have up to fifteen times the number of earthworms in a meter.

1 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/c-elegans-connectome/

2 DailyMail.com

3 United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service

4 Dr. Kevin Butt, Soil Ecologist, The Open University, Milton Keynes, Guardian.co.uk, 2011

5 USDA AgResearch Magazine, May 1995

More reading:

Explore an insect-friendly yard How to improve clay soil Native plants for wildlife Snails: frequent questions Flowers and vines for wildlife