Jump down to: Background • Beneficial • Dragonfly vs. damselfly • Physical description, Head, Eyes, Mouth • Thorax, Wings, Legs • Abdomen • Life cycle, Mating, Eggs • Nymphs, Adults • Lifespan, Migration • Food sources, Habitat, Predators

Introduction

Tom Cruise, in his movie role as the jet pilot “Maverick” in Top Gun, has little over these flying aces of the insect world: Dragonflies can spin 180 degrees in a flash, jet straight up or nosedive straight down, fly backward, and hover! As for speed, their tiny bodies can blast away at 35 miles an hour, And, get this: They can beat their wings 20 to 45 times a second, working each one separately to produce incredible maneuverability. What these insects want, they get! Prey caught in their “gunsights” are doomed, doomed, doomed! And handsome though he is, Maverick has nothing on dragonflies and damselflies in the looks department, either—some of these insects are among the most beautiful on earth.

Background

Dragonflies and damselflies have been executing their aerial skills for 325 million years, since the Carboniferous Period. (By comparison, humans have existed for only 200,000 years.) The largest dragonflies of today have a wingspan of no more than 7.5 inches (19 cm), but fossils show that eons ago, they were 30 inches (76 cm)! Just imagine a hungry one of them jetting toward you!

Around the world, there are about 3,000 species of dragonflies and 2,600 species of damselflies, who are their cousins. Together, they inhabit all continents except Antarctica. North America has about 450 species, roughly two-thirds of them dragonflies.

Damselflies hold the records for both the largest and smallest dragonflies or damselflies in the world. The largest, Megaloprepus caerulatus, belongs to a group of several so-called “helicopter damselflies,” and has a wingspan of 7.5 inches (19 cm). It inhabits Central and South America. Damselflies in the genus Agriocnemis are the world’s smallest, with wingspans of 0.6–0.7 inches (18 mm). Inhabits They inhabit parts of Africa, Asia, and Australia.

In the United States, the largest dragonfly or damselfly is a dragonfly, the Giant Darner, Anax walsinghami, which has a wingspan of 5.0 inches (13 cm). It inhabits the Southwest, and its size makes it easy to spot. The smallest is the Citrine Forktail Damselfly, Ischnura hastat, which is found across the country, but is much harder to see: It has a body that’s about the thickness of a toothpick and one-inch long (25 mm). You may need to get out your magnifying glass for that one!

Etymology and classification

A “dragonfly” isn’t a dragon, of course, and neither is it a fly. How it came to be called that is a bit sketchy. Its first known use goes back to 1626 and most probably arose from one or more myths. The origin of “damselfly” isn’t known, but it was first used in 1815.

Both dragonflies and damselflies belong to the order Odonata (oh-doe-NAW-tuh), a name which comes from the Greek odonto for tooth and is a reference to their serrated teeth.

Dragonflies are in the suborder Epiprocta and the infraorder Anisoptera (an-eye-SOP-ter-uh). “Anisoptera” is a word derived from the Greek words anisos and pteron, for “unequal wing,” which pertains to their hind wings being a bit larger than the forewings.

Calico Pennant Dragonfly, Celithemis elisa, native to the Eastern U.S. (Judy Gallagher / Flickr; CC BY 2.0)

Damselflies are in a different suborder, “Zygoptera,” which is a word formed by the Greek words zugós for “even” and ptera. So, they’re an “even-wing,” because their wings are the same size.

Rambur’s Forktail, Ischnura ramburii, found across the US, Mexico south to Chile, Antilles, Hawaii. (Judy Gallagher / Flickr; CC By 2.0)

They’re beneficial

Dragonflies and damselflies benefit humans by being formidable predators that consume prodigious amounts of nuisance insects like gnats and flies. Mosquitoes, too—giving rise to the name “mosquito hawks,” as some people call them. They’re also a food source for other animals. By the way, neither dragonflies nor damselflies have stingers, and they’re otherwise harmless to humans. If handled carelessly, though, they might deliver a mild bite in self-defense.

Dragonfly or damselfly?

What distinguishes a dragonfly from a damselfly? Several things, and you can spot most of them while they’re perching.

-

- Dragonflies are generally larger and stouter, with a shorter body. Damselflies have a slender body that’s long and dainty.

- The dragonfly’s eyes are huge and sit close together, sometimes touching. Damselfly eyes are a bit smaller and separated from each other.

- The hind wings of dragonflies get broader at the base, while those of a damselfly taper down to the base.

- When resting, dragonflies hold their wings out, and damselflies hold theirs together.

Physical description

Note: Dragonflies and damselflies are mostly alike. So, to make the text less wordy and cumbersome, from here on, the word “dragonfly” will apply to damselflies, too. Any differences will be highlighted.

It’s hard to ignore dragonflies. It isn’t just their aerial acrobatics; their colors also draw the eye. Females are usually less colorful than males, but both sexes of some species scream, “look at me,” in their bright colors of blue, lavender, green, bronze, scarlet, pink, red, orange, or yellow. They’re sometimes even blazingly iridescent. Stripes, bands, or spots may be an added touch. Even those burdened with earth tones can have bright, colorful splotches. And, their wings, broad and transparent, often have spots, bars or bands to pretty them up. Color can define a face, too: Although some are white-faced or black, many are green, red, yellow, or blue.

Main body parts

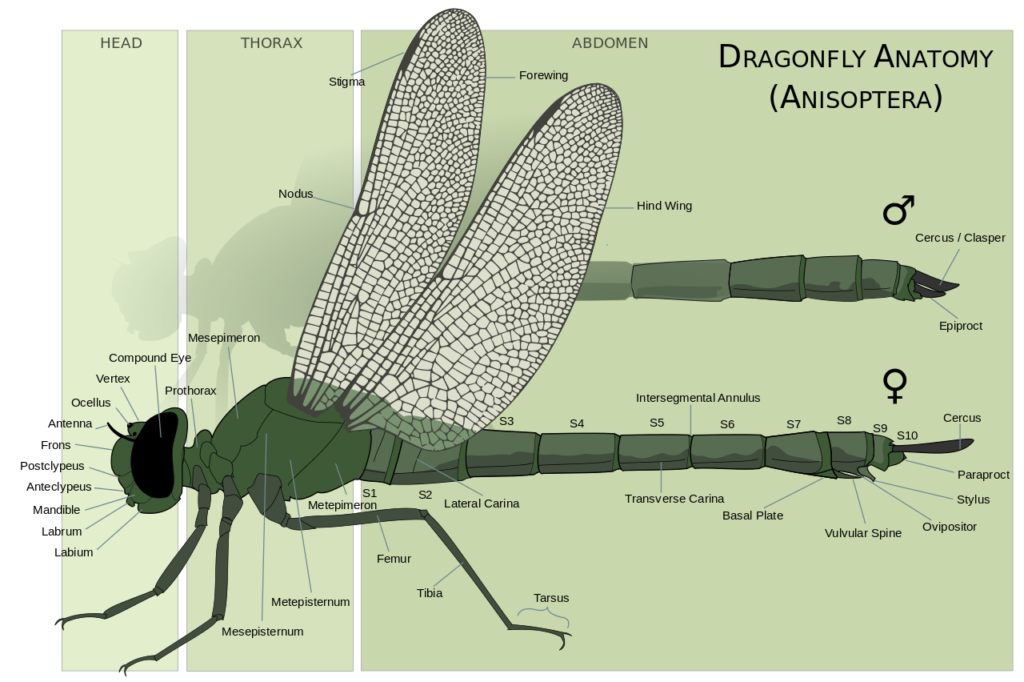

Like all insects, dragonflies have three main body parts: head, thorax, and abdomen. Rather than an internal skeleton, as we have, theirs is external (exoskeleton). It’s composed primarily of proteins and chitin, which provide strength along with flexibility for support and protection. All over the body are sensory hairs that play a role in detecting smells, perceiving temperature, humidity, and wind.

Head

The head is large and has a brain, two compound eyes, mouthparts, and two antennae. More than 80 percent of the brain is used for processing visual information. The mouthparts are large and take up most of the space not claimed by huge compound eyes. The antennae are short, inconspicuous, and play a role in detecting airspeed and direction, and smell.

Eyes

The compound eyes reflect light in striking shades of bright blue, green, red, yellow-orange, brown, or black. They aren’t merely pretty; they’re pretty perfect too. Keen eyesight and nearly 360 degrees of vision make these guys impossible to take unaware. Each eye has 20,000 to 30,000 individual lenses (ommatidia) positioned to see the world at a slightly different angle from all the others. The brain then interprets this sensory input. There are also three simple eyes on the forehead. Called ocelli (oh-CELL-ee), each has just a single lens, for detecting light intensity. Watch a damselfly grooming its eyes and face

Notice the wide spacing between the colorfully reflective compound eyes of this damselfly. (Ronny Overhate / Pixabay; PD)

There’s a noticeable difference between the eyes of dragonflies and damselflies. A dragonfly’s eyes are close together and often touch in the middle. Damselflies have eyes positioned wide apart, forming a bulge on each side of the head.

Notice that the highly reflective compound eyes of this dragonfly are so huge they wrap the sides of its head, and they’re touching, which is typical. The three simple eyes shown here form a triangle with the bottom one being larger than the widely spaced top two. Two short antennae are visible near them. (© chanchai loyjiw / Shutterstock)

Not only do the compound eyes reflect colors, but they see color, too. In fact, a study of dragonfly adults (it isn’t clear whether damselflies were included) found that they see colors better than any other animal in the world. We humans see color as a combination of red, blue, and green because we have three different types of light-sensitive proteins, called opsins. Dragonflies, though, have between 11 and 30 of them, depending on the species. So, they see incredible detail and color combinations that we can’t detect, including ultraviolet light. It’s thought they also recognize polarized light that reflects off of surfaces.

Mouthparts

The mouthparts are a collection of the mandibles (jaws), used for grinding and chewing; maxillae, for holding and manipulating food; and the labrum, labium, and hypopharynx, which are essentially their upper and lower lips and tongue. The mandibles are large, strong, and have sharp serrations.

Thorax

The middle section of the dragonfly’s body, the thorax, has four wings (two on each side) and six legs (three on each side) attached to it.

The wings are different between the dragonfly and damselfly. A dragonfly’s hind wings are broader than the forewings and widen at the base, while those of a damselfly are all the same size and taper down at the base. Dragonflies, while resting, hold their wings horizontally. Almost all damselflies rest with their wings upright and together, in line with their body. The only exceptions are so-called spread-winged damselflies, which are in the Lestidae family; they spread their wings more like dragonflies.

Dragonflies move their wings differently from other flying insects: Instead of a back-and-forth rowing-type action, their wings move downward and backward and then upward and forward. Each has its own muscles, allowing for independent movement and unique agility. They’re crisscrossed with an intricate network of veins that help give them strength. Usually, all four wings have a “stigma,” which is a patch of color on the front edge.

The legs are long and bristly, with claws for catching prey. Curiously, while they’re also useful for perching, they’re too weak to be used for walking.

Abdomen

The abdomen is the back section of the dragonfly’s body. It’s cylindrical and long and consists of ten segments. Within it are the rearmost portions of the nervous, digestive, and circulatory systems, in addition to the excretory and reproductive systems.

The abdomen is flooded with “blood” (in insects, called hemolymph), which is clear instead of red because it doesn’t contain iron, like that of a human. In another contrast, the circulatory system doesn’t carry oxygen. Instead, adult dragonflies breathe through a series of sixteen holes (spiracles) spaced along their abdomen, eight on each side (another four are in the thorax). The spiracles are connected to trachea that network through the body to deliver oxygen to cells and collect carbon dioxide to be expelled. Developing dragonflies— which live in water—breathe through gills. More details about insect anatomy

Males have four appendages at the tip of their abdomen. Two of them are “claspers,” used to hold onto females during mating. The other two are sensory organs called cerci (SUR-sigh; singular: SUR-kus). Females have two cerci, along with a conspicuous egg-laying organ at the tip, called an ovipositor

Senses

Dragonflies have four, and possibly five senses: sight, smell, touch, taste, and maybe hearing.

- Vision: They have keen eyesight, a nearly 360-degree field of view, and can detect the slightest movement.

- Smell: Olfactory sensors in their antennae were long thought to be insignificant. A 2014 study of Blue-tailed Damselflies, Ischnura elegans, however, found they can detect odors of prey and mates. So this is probably true of all dragonflies and damselfies.

- Touch: Sensory hairs are scattered around on the body.

- Taste: The mouthparts have tiny taste organs.

- Hearing: • Most likely not, but this is the focus of some ongoing research, and at least one study detected very slight responses to sound stimuli, even though dragonflies have no tympanic membranes.

Life Cycle

Dragonflies progress in stages from an egg to a nymph to an adult, in a process called incomplete metamorphosis (hemimetabolism). Their lives always involve water. First, they live in it as eggs and nymphs, then as adults that spend their time near it.

Males are unusual in that they have two sets of sex organs. It isn’t known why, but their “primary organ” is on the ninth segment of their abdomen, and their “secondary organ” is located on the underside of the second segment. This is important to point out because it leads to a unique mating experience in the insect world.

Mating

Dragonflies mate in spring through summer, and here’s how it goes: The male first grabs a female by the front segment of her thorax (called the prothorax) or the back of her head with his two claspers and holds on. Just before copulating, he curls his body so he can transfer a packet of sperm directly from his primary organ to his secondary one. The female, in turn, curves her body around until her sex organ comes in contact with his secondary organ. This creates a unique shape called the “wheel position,” but it’s all the more remarkable because it often forms a heart-shape. Damselflies mate while perching, but dragonflies usually start mating while in flight and might then settle on a perch to complete the act.

Sometimes males continue to clutch females until, or even while, they lay their eggs. It’s speculated this to keep females from mating again, thereby ensuring it’s their sperm that fertilizes the eggs. Males are known to scoop out any semen a female may still be carrying from a prior sexual encounter! In the case of at least one species, the Moorland Hawker Dragonfly, Aeshna juncea, females will freeze in midair, plunge to the ground, and feign death to stop being repeatedly pounced on by males! Damselflies mating and laying eggs

Eggs

The female will lay a few hundred eggs, and just as many more every time she mates again. Depending on the species, eggs may be laid directly on the surface, under it, or in or on the stems of water plants. Dragonfly eggs are round, and a damselfly’s are cylindrical and longer. Sometimes nymphs hatch in as little as a week, but it’s typically longer, up to about two months. Some species overwinter.

Nymphs

You can call them nymphs, naiads, or larvae; they’re all the same. But, the first two terms are the most commonly used for dragonfly “babies.” The nymphs usually spend three or four weeks in water, but some go longer. They lack their parents’ beauty. In fact, at first, they’re six-legged, oval-ish, wingless, brown or green, and ugly.

Nature writer, Terry Krautwurst1 describes the nymphs as armored-looking creatures that could have been designed by the creators of the movie Alien. To be sure, a nymph is as lethal as that creature—and just as creepy: Attached to its head is a lower lip (labium) that functions something like a human arm with an “elbow” mid-way, and is fitted with hooks and spines. It’s kept neatly tucked under the head and thorax until suddenly, using strong hydraulic pressure, it bursts forward faster than the eye can see to snatch prey and pull it back to the nymph’s mouth.

Dragonfly vs. damselfly nymphs

Dragonfly nymphs can be distinguished from damselflies by their gills. A dragonfly’s gills are hidden in its rectum (yes, that’s correct). Damselfly nymphs, on the other hand, have three long, leaf-like gills extending from the tip of their abdomen.

A nymph, depending on its species, will shed its skin (molt) eight to 17 times to accommodate its ever-growing body. With each molt, it shows a little more physiological maturity, until finally, it’s ready to breathe air, its wings are prepared to fly, and the sex organs are ripe for mating. It crawls out of the water and clings tightly to a support—a plant stem, twig, or rock—then molts for the final time.

Adult

Its skin splits down the back, and, with great effort, the new adult begins working its way out. If you’re watching the emergence of the adult, these are exciting minutes. But, something seems wrong—this new thing is pale and looks sickly! Where are the bright body colors? And its wings are crumpled and drooping like it’s beginning its terrestrial life in a state of despair. Well, it’s nothing to worry about—like butterflies, the adult dragonfly’s wings won’t be functional until they’re pumped full of fluid that’s held in the body cavity. When that happens, those sad, empty sacks will stretch to full size and gain rigidity, and then they must dry. And, bright colors will come.

This is a precarious, largely defenseless time for the new adult; it’s easy pickings for any predator passing by. After a brief drying time, the wings might be able to clumsily, slowly, lift the body skyward, but an escape would largely depend on luck. Once they’re dry, however, all systems are go.

Downy Emerald Dragonfly, Cordulia aenea, molting for the final time, into an adult form (© Michal Hykel / Shutterstock)

Over the next few days, the adult will feed heavily, and its body color will develop. Then, finally, dressed in its best, it’ll turn its mind to matters of mating. If it’s a territorial male, he’ll stalk out an area near water and defend it against other males. Females, of course, will be welcomed. Non-territorial males may join together to pursue a single female. The females of many species stay away from breeding areas until they’re ready to mate or lay eggs.

Lifespan

Adults can live about two months or so, but probably average less because of predation. Some species, from their egg stage through adulthood, live several years, with most of it spent as nymphs. Adults don’t survive freezing weather, so most dragonflies spend their winter as eggs or nymphs in unfrozen water.

Migration

A few species of dragonflies (probably not damselflies, because they’re weaker fliers) defy the weather by migrating southward as winter approaches. Most go only one-way. But some radio-tagged populations of the Common Green Darner, Anax junius, have been found to migrate round trip. (After emerging in the spring they migrate from the South to the northern US and southern Canada; their offspring make a return trip in the fall.) Other migrating dragonflies include the Variegated Meadowhawk, Sympetrum corruptum, Black Saddlebags, Tramea lacerata, Wandering Glider, Pantala flavescens, and Spot-winged Glider, Pantala hymenaea. Dragonflies migrate like birds

Migratory dragonfly partnership

Food sources

That dragonflies are small and beautiful doesn’t mean they touch the insect world lightly. Scientists at Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Virginia studied the hunting skills of adult dragonflies by fitting them with tiny reflective markers and the use of motion-capture technology. The result? These focused insects catch more than 95 percent of their targeted prey, making them the most successful predators in nature.

Both as nymphs and adults, dragonflies feed voraciously on anything they can catch. As nymphs, they prey on anything smaller than themselves, such as worms, water beetles, mosquito larvae, and small fish. Adults prey on mayflies, mosquitoes, gnats, other insects, and their own kind. There’s even the occasional story of a poor little hummingbird getting caught. Dragonflies usually hunt on the wing, snatching small prey directly into their mouth; bigger prey are caught with their legs before moving them to their mouth. Damselflies are more likely to feed on insects they find on vegetation. In flight, they usually look for prey close to the ground.

Habitat

Dragonflies and damselflies are willing to visit saline water, but most are found wherever there’s freshwater—stream, pond, lake, river, bog, marsh, wetlands, or small backyard water garden. Even springs and lakes in the desert have dragonflies. Some species prefer streams moving through coniferous or deciduous forests, while others choose habitats in grasslands or meadows. Some stay near still or slow-moving water, while others like rushing water.

Like butterflies (and other insects), they’re cold-blooded and must warm their wing muscles before taking flight. So, look for dragonflies to be perched motionless on stems and twigs, basking in the heat of the morning sun, or even shivering their wings to warm them up.

Predators

Dragonflies are especially vulnerable to predators during their egg or nymph stage. Once they become airborne, they’re harder to catch. In the water, they’re preyed on by fish, water beetles, frogs, and other predatory water species. Out of the water, they’re prey for whatever can catch them unaware, including songbirds, waterfowl, large insects (such as robber flies), and spiders.

¹ Mother Earth News Magazine, Sept. 8, 2006, pg. 27

Video: Gille San Martin / Flickr: CC BY-SA 2.0

Earwigs: Move past the myth to meet these unique insects

True bugs: the good, the bad, the ugly

Native plants for a pond