Jump down to: Background • Physical characteristics • Plumage, Feathers • Flight • Migration • Foods, Digestive System, Crop • Calls, Songs, Body Language • Nests • Courtship, Mating • Eggs, Incubation • Life Span, Habitat, Predators

Have you ever watched a hawk lazily riding thermal currents in the sky and wondered what it might be like to feel the embrace of the wind as it carries you higher and higher? To weightlessly sail across panoramic views of majestic scenery, the ocean, cities—and your yard? The ability to fly is one of the distinctive things about birds, and part of what makes them fascinating, but it isn’t what makes them the most unique animals in the world. So, then, what might that be? Their feathers! Nothing else, flying or land-bound, has them.

But, there’s even more to admire about birds. If you watch them, you know how beautiful and entertaining they are. As you follow along here, you’ll find explanations for behaviors you’ve wondered about and discover interesting answers to questions you didn’t know you had. The more you learn, the greater will be your enjoyment of the birds that visit your yard. Guaranteed!

Let’s start with how birds impact our world.

Benefits of birds1

- More than 900 bird species in the world are essential pollinators of wildflowers.

- Birds propagate trees. One of them, the Whitebark Pine, is essential for wildlife in the high mountains of the western United States. It can’t sustain itself without the Clark’s Nutcracker.

- Birds are essential for dispersing seeds for plants, which results in products for humans—foods, medicines, and timber.

- They help control crop pests.

- Scavenger birds eat massive amounts of roadkill, slowing the spread of disease and helping keep our highways cleaner.

- Birds and their eggs are food for other wildlife, and humans, too.

- The existence and fitness of birds in an ecosystem are related to the health of the system itself, an early warning if trouble is afoot.

- Birds are an economic stimulus here and abroad, especially in developing countries. Hotels, restaurants, national parks, and other entities relevant to birdwatchers depend on seasonal influxes of tourists. Birding also encourages sales of equipment, such as binoculars, maps, and guidebooks. (Forty-five million people in the U.S. alone watch birds and spend $41 billion annually on trips and equipment.)2

- Last, but not least, birds are a balm for the human soul. Their beauty and song, their jaunty cheeriness, the freedom of their flight, and their spirited activities combine to draw us gently into oneness with nature. Wherever we are—sitting on a porch, hiking in the woods, or staring out an office window—we’re transported to a calmer state of mind. That’s a fact! Studies show that watching birds reduces stress, depression, and anxiety, and increases cognitive ability.

Background

So, where did these amazing animals come from? Would you believe . . . dinosaurs? A dinosaur fossil found in 2005 had two eggs inside. The embryos had feathers and wings, elongated arms, and a long list of other similarities to birds. In 2006, five well-preserved bird fossils discovered in China were found to be the oldest ever—they date back at least 110 million years to the age of dinosaurs. The fossils are missing their heads, but they’re physically adapted to diving and swimming and are believed to be duck-like. It seems conclusive, doesn’t it? However, there are dissenting scientists who think birds are related to reptiles because of similarities that include scaly skin, laying eggs, and some of their anatomy.

Avibase, a database information system of birds around the world, says there are 10,000 species and 22,000 subspecies of birds. About 1,000 inhabit the U.S. (Do what many birders do: get binoculars and keep a record of how many species visit your yard. Hang feeders to draw them closer.)

Scientific classification

Birds belong to the scientific class Aves (A-veez). Aves contains about two dozen orders of birds. All birds that exist today belong to the sub-class Neornithes (nee-OR-nuh-theez). They differ from their ancient ancestors, in part, by lacking teeth. There are about 165 families of birds, divided into two superorders: Palaeognathae (pay-lee-OGG-nuh-thee), which are mostly flightless, like Ostriches and Emus, and Neognathae, which includes all other birds.

The largest order of birds, Passeriformes (passer-uh-FOR-meez), represents more than half of all species. These are the perching birds, including warblers, wrens, cardinals, finches, woodpeckers, and others we enjoy seeing in our yards.

From teensy to gigantic

Bird shapes and sizes are highly varied. They range from the tiny Bee Hummingbird, Mellisuga helenae, a native of Cuba, about 2.4 inches long (6.1 cm), way, way up to the enormous Ostrich, Struthio camelus, which stands 9 feet tall (2.7 m) and weighs up to 346 pounds (157 kg).

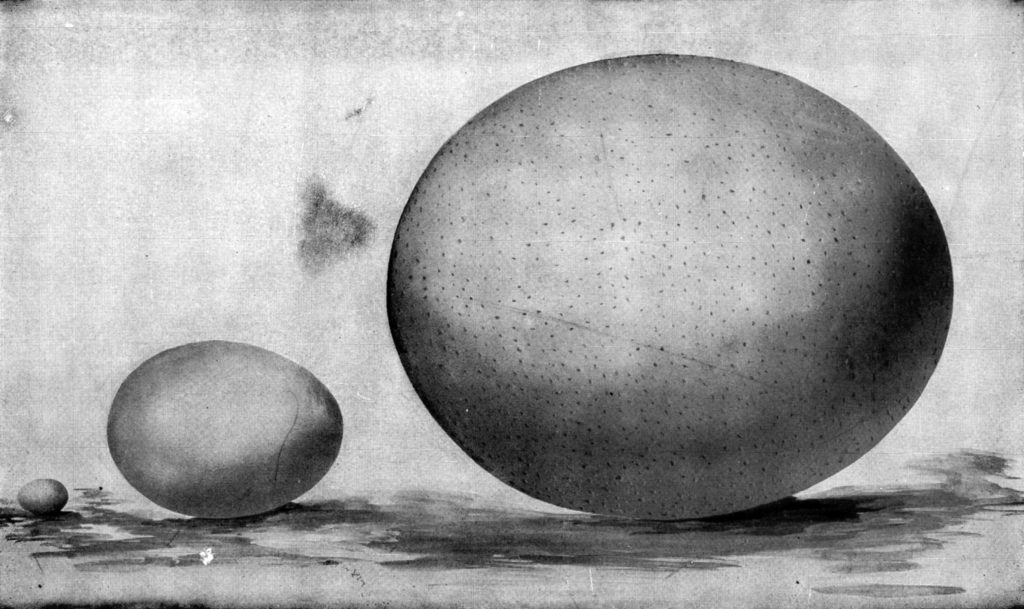

Smallest bird egg to largest, left to right: hummingbird, hen, Ostrich (The New Student’s Reference Work, 1914 / Wiki; PD)

The smallest bird in North America is the Calliope Hummingbird, Selasphorus calliope, about 3.0 inches long (7.6 cm). The largest flying bird in N.A. is the rare California Condor, Gymnogyps californianus,3 which has a wingspan of 9 feet (2.74 m) and weighs 20 pounds (9 kg). The largest N.A. waterfowl is the Trumpeter Swan, Cygnus buccinator, with a wingspan of 6.6 feet (2 m) and weight of up to 28 pounds (12.7 kg).

Physical characteristics of birds

Birds as a group are similar to other animals in that they’re warm-blooded, have two eyes and two ears, and their bones are strong and well-muscled. But there are physical differences between families based on their lifestyle. For example, herons and swans have a long neck for dipping their head deep into water. Many shorebirds have long legs adapted for standing in water while they “fish.” And, a penguin’s body is tapered at both ends for streamlined swimming. Soaring birds, like hawks, typically have long, broad wings.

Eyes, vision: A bird’s eyes fit very tightly within its sockets, which restricts their ability to move up and down and back and forth as a human’s can do. Consequently, if it wants to look at something, say, to its right, it can’t just shift its eyes that way; it must turn its head. The placement of eyes varies, depending on the species. For instance, some birds have eyes located more toward the sides, while birds of prey which need binocular vision for judging distance, have eyes situated in front.

Birds have excellent vision, as you would expect—an eagle, for instance, reportedly can see food on the ground from a mile high! Birds have color vision, including some in the ultraviolet range. Nocturnal birds, such as owls, however, have more limited color vision, because it isn’t needed for hunting in the dark.

Bill or beak: Bill and beak are the same thing, and either word is correct, although they’re highly varied in size and shape. A bird’s bill is a clue to what it eats. Some examples: A Northern Cardinal’s stout bill is designed for cracking seeds. Hummingbirds have a long, narrow bill for sipping nectar from tubular flowers. A woodpecker’s is strong and tapers to the tip, for chiseling trees. Mergansers have a serrated bill with a hooked tip, for grabbing and holding fish. The bill of a Mallard Duck has fringed edges for straining seeds and plants from mud and water.

Ears, hearing: Many owls, along with a few other birds, have tufts of feathers on their head that can be raised or lowered at will. They give the impression of ears, but birds don’t actually have visible ones. Instead, there’s a tube on each side of the head, slightly behind and below the eyes, which leads to internal structures that are much like that of a human. These ear openings are covered by tiny feathers called auriculars, designed to protect them and cut down on wind noise while allowing sound waves to pass through. The feather coverage may be thick or thin, depending on the species. Some diving birds have especially strong ones to protect their inner ears from water pressure.

Although birds lack visible ears, that doesn’t mean they don’t have acute hearing—a Barn Owl, Tyto alba, can hear a rodent rustling about from half a mile away! Birds hear in the 20 Hz to 20 kHz range, similar to ours. See an earhole

Smell: Birds have two nostrils, called nares (NARE-eez; singular: naris). They’re located at the base of the top bill and are used for breathing and smelling. It was long thought that most birds couldn’t smell very well, but a 2007 study4 showed that many, if not most, birds have a well-developed sense of smell. They use it to help navigate, find food, and probably to identify individual birds.

Feet: Birds walk on their toes. Most have four, with one facing backward and the other three facing forward. The spacing of the forward arrangement and their length varies depending on the species. Some birds, like chickens, have a fifth toe that has evolved into a spur, which is used for defense. Waterfowl have webbed toes. This allows them to paddle in the water with ease; like using an oar, they spread their toes wide apart for the backstroke and pull them together for the forward stroke. Some birds use their toes as fingers for holding their food.

Have you ever wondered if birds fall off branches when they’re sleeping or get blown off in a gale? They don’t! There are two reasons: First, their opposable toes allow them to grasp their perch both front and back—if you’ve ever held a bird on your finger, you’ve felt that. Second, they bend their knees and ankles when they perch, and, in response, a system of flexor tendons automatically clinches and locks the toes around the branch—they won’t release until the leg is straight.

Plumage

Some species sport bright feather colors and exquisite patterns. Others, such as House Sparrows, have muted tones. Often, bright coloration is seasonal. The male American Goldfinch, Spinus tristis, transforms in the spring from dull into a striking bright yellow and black, and the male Northern Cardinal, Cardinalis cardinalis, changes from dull to brilliant red.

This change is brought about by shedding (molting) old feathers and replacing them with new ones. Not all birds make such a dramatic transformation from winter to spring, but almost all have a complete molt annually. (The feathers are dropped and replaced gradually, not all at one time—that’s why we don’t see bald birds staring mournfully down at us from their perches!) Birds molt for a couple of reasons: First, feathers wear out, especially those of birds that migrate. Second, breeding season calls for birds to put on their courtship plumage.

The colors of feathers are produced in two ways. One is from color-producing chemicals in the feathers, called pigments. The other is structural elements, such as barbules (tiny, hook-like structures) and air bubbles that cause colors to react with one another and refract (bend) light waves, like a prism. This results in iridescence. The dazzling throats of some male hummingbirds are examples.

Male Costa’s Hummingbird, Calypte costae, refracting brilliant colors (John Sullivan, PD Photo.org / Wiki; PD)

Many birds, especially males, depend on their plumage to catch the eye of a potential mate. Females are typically less colorful. Scientists believe that’s because they generally face more risk while producing and raising young. Plumage color is also related to their environment. Nestlings are always a dull color so they can stay well-hidden in their nests. Many ground-dwelling birds are also a dull color, and rock-dwelling birds are usually gray to camouflage them.

Feather types

Feathers are marvels of complex construction. There are seven types. All are composed of beta-keratin, a protein.

- Contour feathers are all the overlapping feathers that cover the bird’s body and give it a streamlined form.

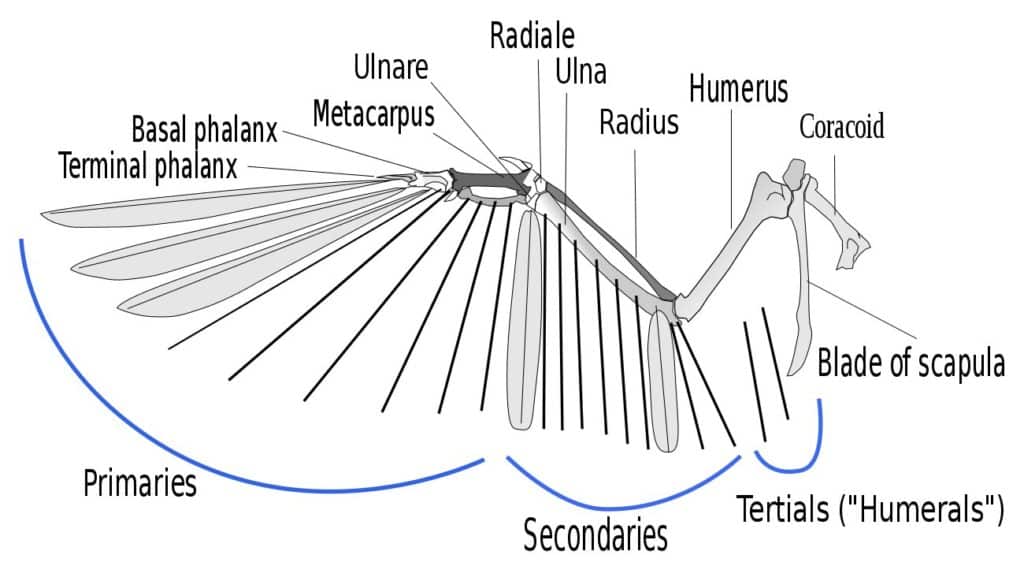

- Wing feathers are strong but light and built to give lift and precise control. They sprout from a stiff linear structure called the shaft. The pointy end, the part of the shaft that’s embedded in the body, is hollow and featherless. (In days gone by, this was used as a writing instrument called a quill.) The feathery, colorful parts are called vanes. Each vane is made up of barbs, which have microscopic barbules and hooks that attach to each other to form a strong but flexible structure that can sustain flight.

- Tail feathers have barbules and hooks and are like a rudder and help provide precise steering and maneuverability.

- Semi-plume feathers have no hooks and are soft.

- Down feathers have neither barbules nor hooks and form a soft, fluffy mass filled with air pockets that insulate the body.

- Filoplumes are short and hairlike sensory feathers with few barbs.

- Bristle feathers are simple and stiff with few barbules and are usually located on the head, probably as protection for the eyes and face.

For more information about feathers: The Feather Atlas Glossary

Feathers are water-repellent. What makes them so? First, birds have a secreting oil gland, the “preen gland” (uropygial gland), located near the base of the tail. Typically, a bird rubs its head or bill in the oil and then spreads it over the feathers using its head. (You’ve probably watched this behavior in your yard.) Second, this action introduces an electrostatic charge to the oil, which further insulates the feathers.

Birds are designed for flight

Getting airborne is a production that relies on hollow bones, which are lightweight but strong, two powerful muscles—the pectoral lowers the wing, and the supracoracoideus raises it— and a high metabolism that keeps a bird’s energy at peak levels.

To fly, smaller birds take a little hop and push their wings downward. Some large birds, on the other hand, jump from a tree branch or cliff or run several steps to gain some speed before taking a leap into the air. Whatever process they follow, the goal is to get some air under the wings to provide lift to the body.

How air flows around a bird’s wing (Thierry Dugnolle / Wiki; PD)

Birds in flight move forward by essentially “rowing:” The wings are wide open to catch as much air as possible on the down stroke, but partly folded on the upstroke to reduce resistance. They can change shape during flight, and feathers can be expanded to control airflow. Tail feathers help provide control, much like a boat’s rudder. Thermal air currents (warm air moving upwards) help birds fly higher or to glide. Watch a good animation of how birds fly.

Unless they’re migrating, birds fly below 500 feet (152 m)—to go higher makes a greater energy demand. Their typical speed is about 15 miles per hour (24 kmh), but they can go faster. Ducks can fly at 60 mph (97 kmh), and a Peregrine Falcon can reach speeds of 200 mph (322 kmh). When they’re migrating, birds generally fly at about 20 to 30 mph (32 to 48 kmh).

Bird migration

More than half of the N.A. breeding birds migrate. And, they face horrendous hazards. Windowglass collisions alone are estimated to kill at least 98 million migrating birds every year. Power lines, windmills, and automobiles take a huge toll. Some drown when they’re overcome by exhaustion while flying over large bodies of water. All this, and predators to worry about, too, including sport hunters.

They put themselves at such risk to find food and favorable weather. They fly north in the spring in anticipation of ample food sources, such as insects, seeds, and berries. In the fall, things wind down as insects begin to hibernate, and flowering plants go dormant. So, they head south where they’re sure to find what they need.

Exactly how migrating birds know where to go is still being researched. What scientists do know is that birds have an inborn sense of direction, fostered by the earth’s magnetic force. Some seem to use the sun or wind direction to help guide them, and they can also use their eyesight to follow geographical landmarks. They learn from their parents.

Some birds relocate only a few miles, as needed. Birds that don’t typically migrate might move farther south if winter conditions become too harsh. This phenomenon, known as “irruption,” occurs when birds move beyond their usual range in response to environmental stressors such as severe weather, food shortages, or habitat changes. It’s unpredictable and not true migration. A new location can become permanent if conditions don’t improve. Birds may also migrate in search of better nesting sites. Some members of a species that typically migrates may begin to remain year-round in one general area. For instance, many Canada Geese, Branta canadensis, known for flying north in the summer to Canada, now stay in southern areas year-round.

For birds that migrate long distances in the spring and fall, their signal is day length. Longer days in the spring send them north, and shorter days in the fall start them heading south. They fatten up ahead of time and begin to form flocks. When weather conditions are just right, they’re off! Some fly at night (most songbirds do). They generally fly at 20 to 30 miles per hour (32–48 kmh) and at heights between 1,500 and 6,000 feet (0.5–1.8 km). Some go much, much higher. Bar-headed Geese, Anser indicus, have been recorded flying at more than 5.5 miles high (8.8 km)!

Birds may fly unbelievably long distances. Some Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Archilochus colubris, which weigh a scant 0.125 ounces (3.5 g), make a 600-mile (966 km), non-stop flight across the Gulf of Mexico between the Yucatan Peninsula and the southern U.S. coast twice a year. The champion migrator, though, is the Arctic Tern, Sterna paradisaea, which migrates about 44,000 miles (29,000 km) round-trip (you read that right!) between Greenland and the Antarctic every year, making stops along the way. The champion non-stop fliers are Bar-tailed Godwits, Limosa lapponica. A female was tracked flying 7,145 miles (11,500 km)—nonstop—from Alaska to New Zealand! She’s just one of 70,000 who make that journey in September and return the following March. They do it without eating or drinking over a period of about nine days.

U.S. birds typically fly one of four main routes because of geographical formations, such as mountains, coastlines, waterways, and deserts, that either help or impede their progress. They generally follow the same route year after year, but they’re capable of changing their pattern.

Food, eating, digestion, crop

Depending on the species, birds eat seeds, nuts, fruit, nectar, insects, fish and other sea creatures, reptiles, amphibians, other birds, mammals, and carrion. If it’s organic, one bird or another will eat it.

The way they swallow those foods is unique. Birds don’t have a “soft palate,” which is a soft but muscular tissue located on the roof of the mouth toward the back. Many other animals, including humans, have one. (Try to swallow without allowing your tongue to touch the roof of your mouth.) Lacking this, birds must compensate by tilting their head upward, so that food and water glide down into their throat to be swallowed. This may be most easily witnessed at a birdbath, where you can see one fill its bill with water and then slightly tilt its head.

Some birds use their bill to crush or break open seed shells, while others use it to tear food apart. Either way, birds don’t have teeth and don’t chew their food. But they produce a lot of saliva, which helps to glue some foods into a ball for swallowing.

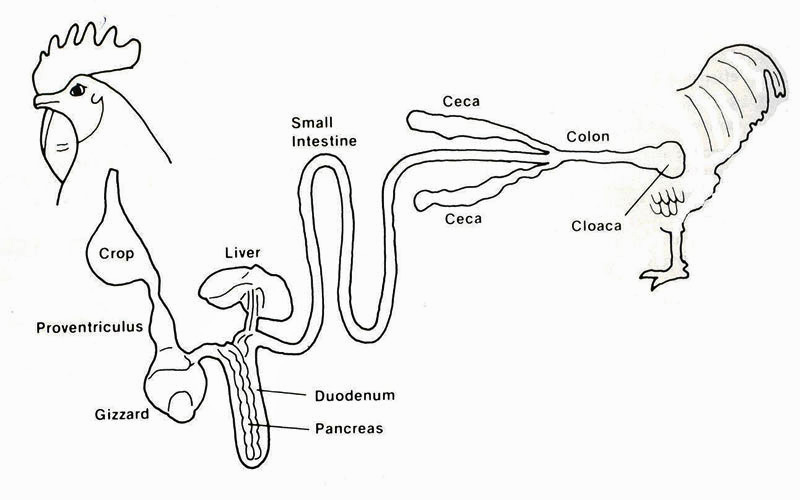

Crop

You’ve probably heard of a bird’s “crop,” but aren’t quite sure what it is. It’s a muscular pouch located at the end of the esophagus of some, but not all, birds. It plays a role as a storage and food-softening chamber: if a bird eats more food than its stomach can hold, the extra can remain in the crop, and also soften up while it’s there.

The crop is developed most highly in birds that eat seeds or vegetation. With pigeons only, the crop produces a milk-like product that the female uses to feed her hatchlings. They’re the only animals other than mammals that do that, and the same hormone, prolactin, controls its production.

Two-chambered stomach

The crop leads to a two-chambered stomach. One chamber, the proventriculus, secretes stomach enzymes for breaking food down. Food passes from there into the other chamber, called the gizzard (ventriculus).

The gizzard is very muscular and grinds up the food. Basically, it takes the place of teeth and is essential for breaking down tough seeds and fibrous vegetable matter into a digestible form. (If you’ve eaten a chicken gizzard, you know how tough it is.) Some species of birds swallow small stones, which help in the grinding process by scraping against the food. As you might deduce, birds that eat softer foods have weaker gizzards.

Birds of prey, like hawks and owls, tear apart and eat the entire body of their prey. That means everything! The meat, organs, bones, teeth, feathers, and fur all go down. Sometimes prey is swallowed whole. Either way, any matter still in the gizzard after several hours is formed into a pellet and eventually expelled through the mouth.

The rest of the digestive tract is similar to that of mammals, except for the cloaca (klo-A-kuh), a cavity at the end of the large intestine. It serves as a collection and discharge chamber for all bodily waste products, as well as semen and eggs. We’ve all seen white bird poo (often where we don’t want it!), but we’ll never see bird urine. That’s because a bird’s body is very conservative with water. Instead of combining water with waste material to form urine, as mammals do, birds process it into a whitish powder or paste called uric acid. That accounts for the color of their poo.

Communication: calls, songs, body language

There’s a difference between a bird’s “call” and its song. A call is a few simple notes used for non-sexual communication. It’s used to express territory ownership, keep track of one another, and show aggression and distress. Alarm calls warn of predators. Young birds call for food, and migrating birds make calls to keep the flock together. Birds can distinguish the calls and songs of individual friends and family from those of outsiders.

Nearly half of the birds in the world don’t sing. All of those that do belong to the order Passeriformes—the songbirds. Their songs are an additional means of communication. They’re more complicated than calls and often lovely, specially designed to entice a desirable mate.

California Thrasher song

(Attribution: K. Sasahara, M. Cody, D. Cohen, C. Taylor / wiki cc by 2.5)

Birds have a unique vocal organ, called a syrinx (SEAR-inks), located just where the trachea branches into each of the lungs. Half of the syrinx sits at the top of each bronchus and is capable of producing sound waves as passing air vibrates it. Each side can make its own sounds. Depending on the species, some produce rising notes from one side while simultaneously singing falling notes from the other side. Some species alternate sides, a note from one side, then a note from the other, back and forth. In still another variation, there are birds that produce all their high notes from one side and all the low ones from the other.

Singing is triggered by the approach of warmer weather and longer days. A series of hormonal reactions in the brain tells (mostly) males that it’s time to burst into song and show off the best they’ve got. They commonly do it in the early morning and late afternoon, from a perch at the top of a tree so their songs will carry far and wide. By the time nesting season is over, the songs will have stopped.

They learn to sing in the same way human infants do–they mimic their parents. If a Northern Cardinal, say, grew up listening only to chickadee daddys, it would sing little chickadee songs! Baby birds refine their songs during their first year.

Many sing only one or two songs, while others have quite a repertoire. Some wrens have over a hundred different songs. Mockingbirds, which are well-named, can sing over two hundred, many of them tunes “stolen” from other songbirds. They aren’t the only mimes: Starlings, crows, Mynahs, parrots, and others also mimic other birds, as well as human voices and other noises.

Body movement and posture are other ways that birds communicate. They may crouch, fluff their feathers, flap their wings, share kisses, and more, to express various emotional states. A territorial dispute might find them fighting. Males will fight over females. Some birds are fearless when their nest is threatened and will feign an injury and move away from a nest to lure a predator. Birds will dive-bomb predators, too, and a sharp bill can be injurious.4

Nests

Nesting materials may include grass and other vegetation, twigs, yarn, feathers, cobwebs, insect parts, flowers, cotton, hair, mud, and even miscellaneous human-made items that catch a bird’s fancy. Nest-building gets better with practice.

Nest-building is usually done by the female, but males of some species help. Most build a new nest each time they mate, but a few use the same nest for years. The site for a nest varies, but the goal is always to camouflage it for the safety of the eggs and babies. With some species, the female selects the place. In other cases, the male does, or both sexes do.

Not all birds build a nest. Nightjars, Caprimulgidae, lay their eggs directly on the ground. The White Tern, Gygis alba, a seabird, lays her eggs on a bare limb. (Imagine trying to keep it there, warm and safe, for five weeks!) The male Emperor Penguin, Aptenodytes forsteri, incubates an egg by holding it between the top of his feet and his warm belly. The Burrowing Owl, Athene cunicularia, nests in the old tunnels of Prairie Dogs, ground squirrels, or the like.

Bird Courtship

Hormonal signals in the brain give males and females the itch to find a partner beginning in early spring.

Males tune up their most beautiful arias in hopes of tickling the fancy of lovely females. But that’s not all there is to do. They also must wear their most beautiful plumage and perform visual displays better than all the other competing males. Depending on the species, they might have to strut, jump up and down, inflate their chest, flap their wings, or bow. Male cranes perform elaborate dances. Some male birds bring a gift of food. Others try to impress by building several nests for an intended to choose from.

Females are picky; they won’t settle for any old yokel! There’s much at stake–they want partners that’ll father handsome, hearty, smart offspring. But once the deserving males have won their prize, it’s time to get down to family business.

Pairs often show each other “tenderness” by touching bills, snuggling together, or preening each other. Mating occurs in any place the couple finds suitable, like on the ground, in trees or shrubs, or in water. Swifts and swallows mate in the air. Some birds mate for life, but most bond for only the breeding season or part of the season. Some species form pairs long before the spring breeding season.

Mating:

Except for waterfowl and the large flightless species, males don’t have a penis. The male’s sperm is produced in his testes, just like all other male animals, but it’s stored in his cloaca (which, remember, is the opening at the end of the body).

If you’ve spotted birds in the act of mating, you’ve noticed that the male is forced to relinquish all dignity as he frantically flaps his wings to keep from sliding off the female—which he inevitably does! It seems like a futile effort, but all it takes is a second of his cloaca and her’s to meet in the “cloacal kiss.” In a flash, his sperm transfers to the female. The sperm enters her oviduct and penetrates the yellow yolk of her eggs, which are already moving down from her ovaries. (Females can lay unfertilized eggs, but that, of course, won’t result in offspring.

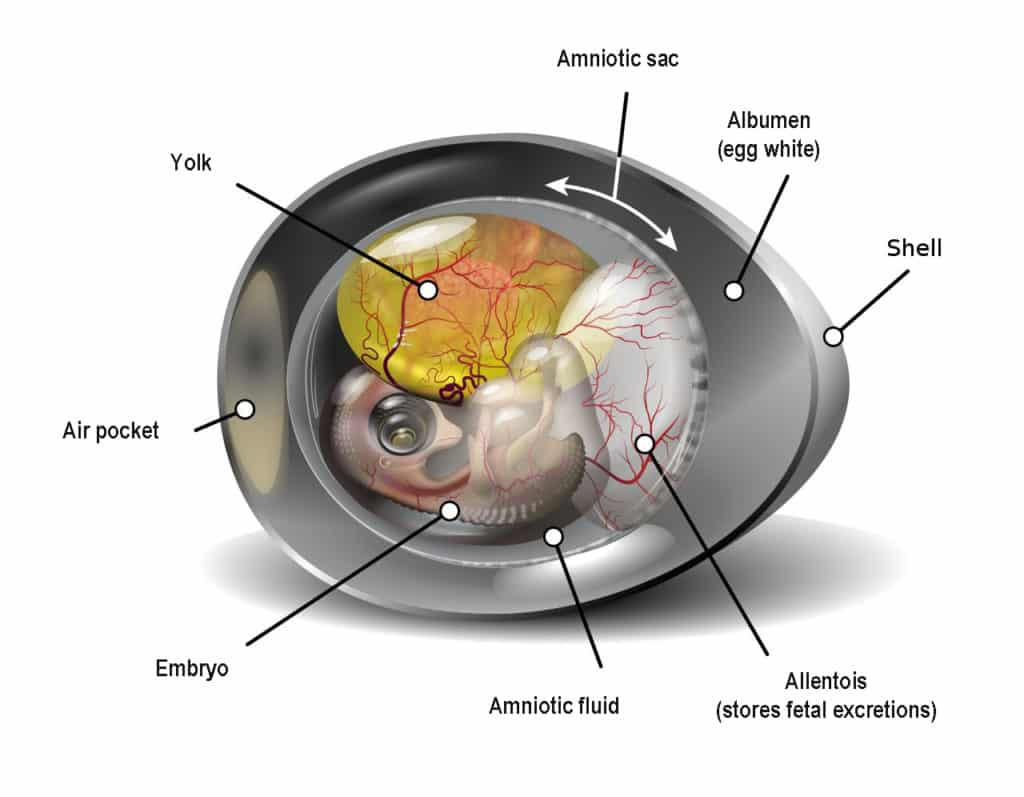

From there, a fertilized egg continues slowly through the oviduct. During its journey, egg-white, a protective material made of albumen (a protein) develops around the yolk. The yolk itself is a soup of nutrient-rich food for the developing chick.

The eggshell is made mostly of calcium carbonate and develops over a period of about twenty hours. There’s a lot of variation, including the thickness of the shell and its color. Birds that lay their eggs in visible locations, such as ground-dwelling birds, have cryptically colored eggs to camouflage them, but some birds (like chickens, for instance) may lay all-white eggs.

Eggs, incubation, hatching

The number of eggs laid (called a clutch) varies depending on the species. Mourning Doves, Zenaida macroura, lay two, while the Blue Jay, Cyanocitta cristata, lays up to seven. For Mallard Ducks, Anas platyrhynchos, it may be as many as thirteen eggs. Songbirds usually lay one egg a day, generally in the morning. Some larger birds lay them more erratically, like one every few days.

Incubating habits differ between species. Usually, once all the eggs are laid, the female sits on them around the clock to keep them warm, taking only short food breaks. Males of some species help by taking turns or bringing food to the female. In other cases, the female incubates, and the male stands guard when she leaves the nest to eat. Male sandpipers, Scolopacidae, take on all the work of parenting by both incubating the eggs and caring for the nestlings. The same is true of Ostriches, Struthio spp., and some other large birds.

The incubation period of most passerine birds is twelve to fourteen days. The developing babies initially get oxygen through membranes that channel air to them from pores in the shell. When they’re ready to hatch, the chicks start breathing with their lungs for the first time and need a new source of air because they’re facing the laborious task of chiseling their way out of the shell. Fortunately, there happens to be an air pocket waiting for them behind a membrane at the round end of the egg, and they break a hole in it. (This air pocket is the hollow area we see when we peel a hard-boiled egg.)

They’re now in a race to survive—they have to break their way out of the shell before they run out of such a tiny bubble of air. With the aid of a specialized, strong muscle on the back of their neck and a sharp, bony bump on the tip of their upper bill, called the “egg tooth,” they make a difficult, time-consuming escape. The tooth later drops off, and the muscle shrinks. If a baby can’t make it out, it’ll suffocate. The parents seldom help.

When they hatch, the young of most ground-feeding birds are covered with down. As soon as they dry, they start following their parents around and feeding on their own. These birds are referred to as precocial (pre-KO-shul). Birds that nest in trees or a hole have a shorter incubation period, however, and the hatchlings are blind and bald when they hatch. They’re called altricial (al-TRISH-ul), and their parents feed them until they’re fully feathered and can fend for themselves.

Altricial parents carry high-protein foods, nuts, and insects, to their young, both while they’re still in the nest and for several days after they leave it. It’s a busy time for the parents (or parent, as the females of some species raise their young alone). They must feed themselves along with two or more offspring several times a day. Most babies fledge two or three weeks later when their feathers and wing bones have grown a sufficient length for flight. Often, though, they hop out of the nest before they’re quite ready.

Fledglings

You might see fledglings hopping around on the ground in a coat of camouflage-colored feathers. Their anxious parents are nearby—even if you don’t see them, they see you. Some parents issue a stern warning to leave their fledglings alone by scolding, dive-bombing, or pecking at intruders. (By the way, unless you’re sure a fledgling has been abandoned, it’s best to leave it alone. An exception would be to gently and quickly move it under the nearest shrub for protection from predators if you’ve found one fully exposed in the yard.) Proper rescue, care for injured, orphaned wildlife

The fledglings will follow their parents around, mouths wide open, wings fluttering madly, in a pitiful, begging pose. “Feed me, feed me, like you’ve always done before.” The parents do just that for several days while their offspring learn the ropes: how to find food, what to eat, what a predator looks like, and techniques for survival. Eventually, in a few cases quite a long time, the parents begin to ignore them or even chase them away when they beg.

Life span

Birds live a long time if they survive predation. The U.S. Geological Survey has records of banded wild birds that have later been caught again, allowing them to track the minimum age of numerous species from the original date on the bands. (Each bird, of course, is always at least a little bit older than the date it was banded.) There’s a Common Grackle, Quiscalus quiscula, listed at more than twenty-three years old, a fifteen-year-old Northern Cardinal, and a sixteen-year-old Blue Jay, among many other perching birds. A Whistling Swan, Cygnus columbianus, is listed at more than twenty-five years of age. The champ, as of 2024, is a seventy-two-year-old wild, female Laysan Albatross, Phoebastria immutabilis, named Wisdom. She lives in the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and is still producing offspring!

“Wisdom” the Laysan Albatross, Phoebastria immutabilis, with her new chick. Photo taken in 2011. (USFWS / Wiki; PD)

Habitat

Seventy-seven percent of birds live in forests. But all other environments have birds, as well: Mountains, prairies, grasslands, farmland, seasides or rocky, barren shores, marshes, lakes, ponds, and rivers. There are birds that spend most of their lives on the open ocean, and others live in the desert.

Predators

On the ground or in trees, birds are prey for any carnivore that can catch them. In nests, the babies are prey for other birds, such as Blue Jays, as well as squirrels, raccoons, and others. Bird eggs are food for snakes and other animals. Territorial birds sometimes toss eggs out of their nests or deliberately break them. Raptors and hunters target them while they’re in flight. Each year, millions of birds die during migration, from flying into window glass, skyscrapers, towers, electric lines, and wind turbines. Collisions with cars kill millions more.

1 Primary source: Audubon.org

2 2016 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report

3 There are only about 440 in existence, nearly half of them in captivity.

4 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft., “Birds Have A Good Sense Of Smell,” Alderleaf Wilderness College

More reading:

How to attract more birds to your yard

Choose a birdhouse with these best features in mind

These are the birds of ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’ song

Birds gone bald!

Cool facts about birds that will visit yards N–S