Background

Origin

Itty-bitty to colossal (on a frog scale, that is)

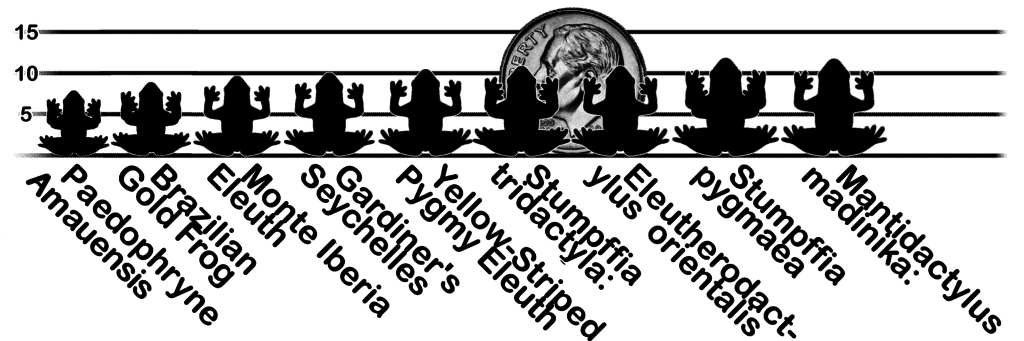

Frogs are remarkably varied in size. The largest in the world is the endangered Goliath Frog, Conraua goliath, native to Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. It grows to 12.6 inches long (32 cm), without its legs extended, and weighs up to 7.17 pounds (3.25 kg). Imagine coming across one of those! Way, way down at the opposite end of the scale is the world’s smallest frog, as well as the tiniest known vertebrate, Paedophryne amauensis. Found in Papua Guinea, it’s only 0.30 inches long (7.6 mm), the size of a housefly! Only slightly larger are three species discovered in Madagascar with the humorous Latin names Mini mum, Mini ature, and Mini scule! The largest, Mini mum, could easily fit on your thumbnail.

In the United States, the largest native frog is one you might guess: the American Bullfrog, Lithobates catesbeianus, which is 3.75–6.0 inches (9.5–15 cm) long and weighs up to 1.13 pounds (513 g). The smallest is the Little Grass Frog, Limnaoedus ocularis, which, at a mere 0.75-inch (19 mm) would fit on a penny. The largest toad in the US is the Sonoran Desert Toad, Incilius alvarius, at 7.5 inches (19 cm) long. The smallest toad is the Oak Toad, Bufo quercicus, from 0.7 to 1.25 inches (18 to 3.2 mm) long.

Physical description

A frog can be distinguished from a toad. Once you know, it’s easy: Frogs have moist, smooth skin; a slender body; visible eardrums on the sides of their head; and no parotid glands. Tree frogs have toe pads. Toads have dry, warty-looking skin, a heavier-looking body; visible eardrums; visible parotid glands; and no toe pads.

| Frog | Toad |

| Skin smooth, moist | Skin dry, warty-looking |

| Slender body | Heavier body |

| Usually lives near water | May live far away from water |

| Visible eardrums | Visible eardrums |

| Tree frogs have toe pads | No toe pads |

Head

A frog’s large bulbous eyes are involved in swallowing. The eardrum is the large circular area below the eye. (LisaAnn_37/Pixabay; PD)

Eyes

Frogs have excellent vision in both daylight and dark, with a field of view that allows them to see to the front, sides and partially behind. This is important for spotting predators because a frog can’t turn its head or move it up and down.

The upper and lower eyelids are underdeveloped and move very little. To completely close their eyes, frogs must draw their eyeballs deep into their sockets, which pulls the eyelids together. They have a transparent membrane that can cover their eyes, which protects and cleans them.

Because their eyes are situated at the top of the head, species that spend much of their time in water can sit motionless with only their eyes above the surface. All the better for watching for unwary insects they can eat. Toads spend most of their time on land.

Frogs’ eyes have a surprising function beyond vision. It seems far-fetched, but it’s true! They help frogs to swallow! When a frog catches prey, its eyes close, drop down into the roof of its mouth and help push the food down the throat!

Hearing

Frogs have excellent hearing. Their external ear is a sealed, circular membrane on each side of the head, called a tympanum, or eardrum. (It can easily be seen just below the eye in the photo above.) It both transmits sound waves to the inner ear and keeps water out.

Like humans, frogs have a middle and inner ear. At the end of the inner ear is a membrane thought to help as protection against deafening noises—which they produce themselves! Some frogs have calls that are so ear-piercing they can be heard a mile away! In 2008, scientists discovered a frog species living near a noisy area in China that can tune its hearing to different frequencies, like a radio knob, effectively tuning out objectionable noises or even the calls of other frog species.

Other senses

Frogs are sensitive to touch and have a good sense of smell. Their sense of taste is excellent—in fact, they’ll reject foods they don’t like.

Mouth

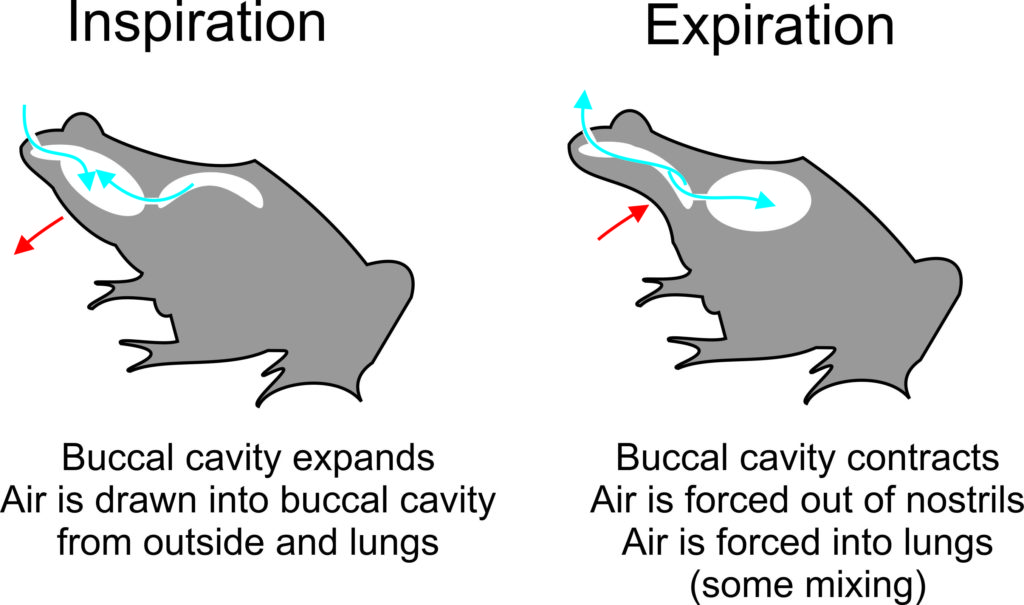

Breathing

Torso

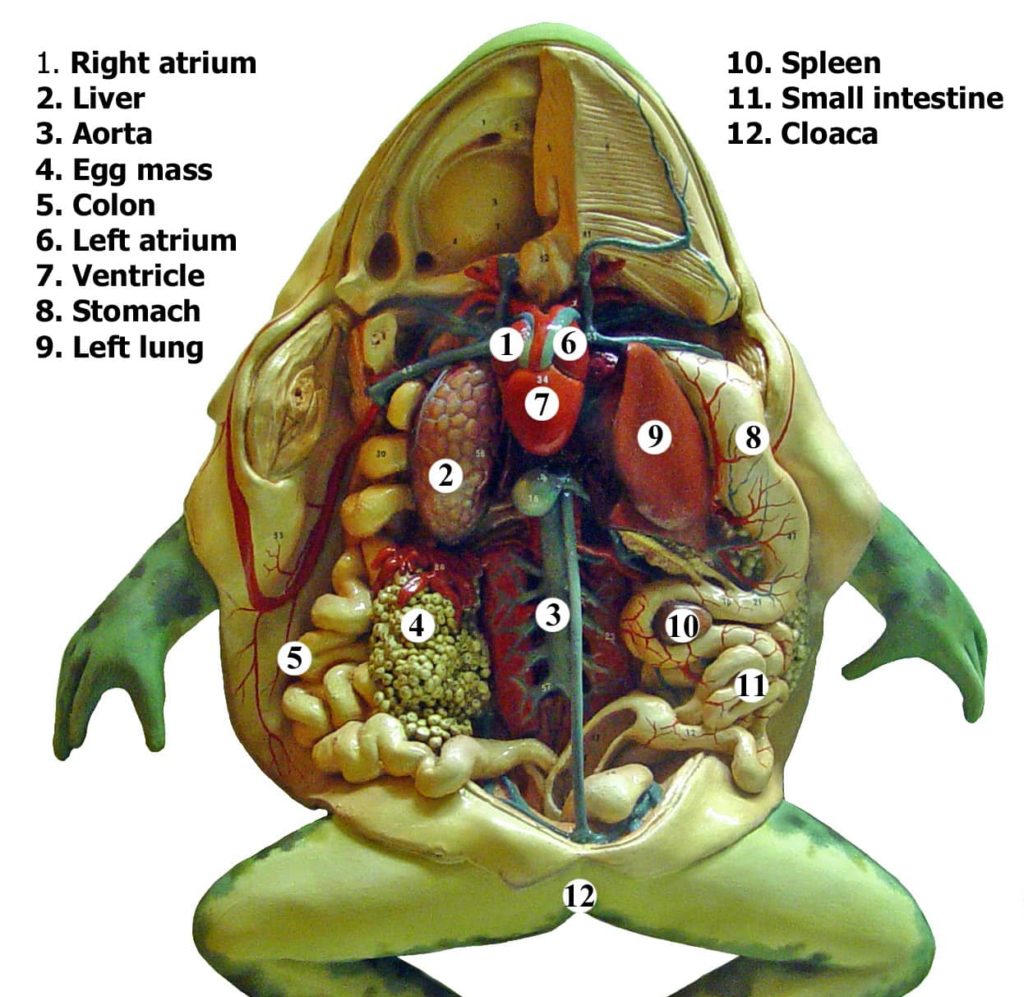

Frogs have a heart, two lungs, two kidneys, stomach, liver, small intestine, large intestine, spleen, pancreas, gallbladder, urinary bladder, and ureter. There’s also a urinogenital duct which serves as a passageway for waste products, sperm, and eggs to exit the body through the cloaca (anus). Males have two testes and females have two ovaries, in addition to other organs related to reproduction.

Frogs have two arms and two legs made up of the same kind of bones humans have. Their arms have a humerus, fused radius and ulna bones and four fingers. The legs have a femur, fused tibia and fibula bones and five toes. The shoulder blades and collarbone are shaped similar to our’s, also.

Webbing

Their hind legs are long, with webbing that stretches between the toes. Frogs that spend a lot of time in water have longer legs and more webbing than more terrestrial species. Webbing is valuable for helping them to paddle through water. There’s an unusual family of frogs called “gliding” frogs that stretch their toes wide, and the webbing acts as wings, allowing them to jump from high places to lower. They “fly” from tree to tree in this manner. Watch them fly

Tree frogs are an example of those with less webbing. They spend all their time on land once they become adults and it covers only half or less the length of their toes. Their toes differ in another way, too: They’re equipped with mucus-tipped, bristly pads that help them stick horizontally or even hang from the underside of leaves. Toads don’t have webbed feet.

Most frogs lack claws, but spadefoot toads, which live in dry habitats, have claw-like growths on their hind feet, used for digging burrows. Their method of execution is interesting: As they dig, they move backward in a circle until the hole is deep enough for them to disappear into it.

Some species of frogs walk like a lizard, but most hop as a standard method of locomotion on land. Frogs are powerful jumpers with muscles and tendons that perform like springs. Their arms are of little use in jumping, but they help to cushion the landing. An American Bullfrog, cleverly named Rosie the Ribeter, set the still-unbroken record for the longest frog jump in the US in a single bound at the Calaveras County (California) Fair in 1986—21.6 feet (6.6 m). How frogs jump so high. Watch a walking toad.

Skin

The outer skin, or epidermis, of frogs is moist. The moisture comes from mucus that’s secreted by glands in the lower layer of skin, called the dermis. The skin of toads is usually dry and bumpy, but it secretes moisture, too, and they’re able to retain it longer. Still, their skin is drier than that of frogs, and that enables them to live farther from water. Some even live in arid habitats, where they dig burrows to escape skin-drying conditions.

Frogs shed (molt) their skin about once a week. They loosen old skin by twisting their body all around, then pull it off over their head in one piece, like a sweater. They don’t leave it lying on the ground, like a dirty garment—they eat it.

Coloration

It’d be pretty hard for any animal to top the flashy colors of the Red-eyed Tree Frog and the poison dart frogs. Certainly, most other frogs can’t, as they typically wear camouflage colors in shades of brown, gray or green.

Chromatophores

Another example is the Gray Tree Frog, normally colored green, gray or brown,, depending on its surroundings. But some are reportedly almost black and can change their color to nearly white. And, there’s a small African frog that’s creamy-white and lives in the white blossoms of a particular lily. When the flowers die and turn brown, it turns brown, too.

Toads and warts

Toads (and some frogs, too) have warty-looking bumps all over their body. But contrary to common myth, they aren’t warts, and they don’t cause humans to get warts by touching them.

Those “warts” aren’t warts! Notice, too, the long, puffy poison gland located beside the eardrum. Common Toad, Bufo bufo. (leoleobobeo / Pixabay PD0

The ‘warts” are a mix of two types of glands: mucous glands, which can sometimes be poisonous, and granular glands, which produce a much more toxic substance, called bufotoxin.

Bufotoxin

Poison dart frogs

Golden Poison Frog, Phyllobates terribilis, world’s most poisonous. (Lwp Kommunikáció / Flickr; cc by 2.0)

One of the most toxic animals on earth is the Golden Poison Frog, Phyllobates terribilis, that inhabits Central America and South America: Just one milligram of its poison can kill between 10 and 20 people. There are no frogs or toads in the US that are lethal to humans unless ingested. Even the poisonous Cane Toad, Rhinella marina, of the southern US can be safely handled if done with care.

Communication

Small-headed Tree Frog, Dendropsophus microcephalus, male, with inflated vocal sac. (Brian Gratwicke / Flickr; cc by 2.0)

A lot of people are familiar with the deep croak of American Bullfrogs, but frog calls also include chirps, trills, twitters, peeps, clicks, twangs and other sounds that defy description. In order to attract the right mate, each species has its own special call. As for the frog that goes, “ribbit, ribbit, ribbit,” it’s the Pacific Tree Frog, Pseudacris regilla. Listen here.

Estivation

Hibernation

Frogs that withstand freezing

Reproduction

Eggs

Frogs have developed some interesting patterns of parenting. Some males, depending on the species, may watch over the eggs, carry them from a moist place, such as the water in a cupped leaf, to a wetter place, or, like Darwin’s Frogs, Rhinoderma darwinii, of Chile and Argentina, carry eggs in their vocal sac until they hatch into tadpoles! The eggs of Suriname Sea Toads get embedded into the skin on their mother’s back during mating and she carries them around through the tadpole stage. When they surface, they’re full-grown toads!

Tadpoles

Tadpoles, sometimes called pollywogs or froglets, eat voraciously, first on algae and later on tiny water animals, small fish and insects.

Their appearance is quite different from their parents. At first, tadpoles have an oval-shaped body with gills, a long tail and, like their parents, large eyes. Then body parts begin to develop: their tongue, teeth, some of the bones, kidneys, glands and gonads. Their legs start to grow, and finally, the tail is absorbed into the body. The gills are absorbed, too, as the lungs develop. Tadpoles move through water the same way fish do. When they become adults, they leave the water for a more terrestrial life or continue their water lifestyle, depending on the species. Watch development from egg to frog

Lifespan

Captive frogs are known to live 15 to 20 years, but just how long they live in the wild isn’t known, because they’re hard to track. Some have lived at least five years, but predators probably eat most within days of their leaving the water.

Food sources

Defenses

Predators

Humans are the biggest threat to frogs as a result of habitat destruction, pollution and pesticide use. Also, many people eat them. Millions of frogs die during scientific research or classroom experiments. Some are captured and kept as pets. Other predators are snakes, lizards, large spiders, fish, birds, and foxes and other mammals. Automobiles also kill frogs in the spring and fall as they cross roads while migrating between shallow, summer breeding ponds and deeper ponds for hibernating.

Habitat

Most frog species live in tropical rainforests, but they’re native everywhere, except Antarctica and some islands. They’re found in all inhabits where there’s water of some kind, from deep water to quiet creeks and ponds.

Toads are willing to move farther from water, and some species thumb their little toad noses at water pretty much altogether and live in arid places where they bury themselves during dry spells and emerge only when it rains. But otherwise, frogs live close to water where they can be spotted on the ground or in the water. Tree frogs spend most of their time in trees or tall vegetation nearby.

Frogs as bio-indicators

Frogs are considered to be bio-indicators because their disappearance in an area indicates that something unhealthy in happening in the environment, something has gone amiss. Their permeable skin absorbs toxins easily, whether they’re in the water or on land. When they start dying off or develop mutations, scientists take note. Broadly speaking, where frogs are safe, humans are safe.

Environmental threats to frogs

“Toughie,” the Fringe-limbed Tree Frog, Ecnomiohyla rabborum. (Brian Gratwicke / Wikimedia; CC BY 2.0)

“Toughie,” shown above, was given his name by the Atlanta Botanical Garden where he lived. He was the last of several dozen rescued in 2005 from an outbreak of Chytridiomycosis in Panama. His species became extinct in the wild. When he died on September 26, 2016, he was the very last one of his kind.

Chytridiomycosis, a fungus disease that sometimes kills off entire populations of frogs in an area, is just one of a long list of threats to the future of frogs. The most significant is ongoing habitat loss and fragmentation. Plus, there’s air pollution, and chemicals, too—particularly pesticide run-off into water that causes hormone disruptions and even kills. Humans are over-harvesting frogs for food. Even lights are damaging because they reduce mating behavior in some species.

Nearly 200 species have gone extinct in our own lifetime! Dozens more are on the brink, and some only exist because they’re in protective captivity. Frogs worldwide are essentially huddled at the end of a dead-end street with a steamroller barreling toward them.

What you can do to help frogs

Avoid pesticide use in your yard (this helps all other wildlife, too), turn off porch lights, at least in the spring. Build a frog pond, provide plantings for them to cool off and hide under. Use native plants because tadpoles need their preferred plants for eating and hiding. Don’t add American Bullfrogs to your pond, they’re thought to contribute to Chytridiomycosis infections. Don’t flush medicines and chemicals down the toilet. On a wider scale, donate to conservation programs and always put trash in proper receptacles.