You may be wondering what Coyotes have to do with an urban backyard wildlife habitat. So, here it is: If your neighborhood offers plenty of good cover for hiding—wooded or brushy areas, thickets, tall grasses—a Coyote may be visiting your yard every night. It might drink from your dog’s water dish, pounce on mice nibbling up spilled birdseed, go fishing in your pond, and search your compost bin for dinner leftovers. No? Look again at the Coyote above; it’s relaxing in an urban yard! A study1 of 105 medium-sized to large cities determined that ninety-six had Coyote populations, including New York City.

Background

Coyotes, Canis latrans, are native to North America. Fossil evidence shows they evolved from a coyote-like carnivore that existed five to six million years ago in the Miocene to early Pleistocene Epochs. They’ve existed as we see them today for at least a million years. Their scientific family, Canidae (CAN-uh-dee), includes wolves, foxes, jackals, dingoes, dogs, and other dog-like animals.

Originally, Coyotes inhabited the grasslands of the northwestern United States. As humans entrenched themselves in their habitat, Coyotes were forced to find new homelands. The disrupted, growing populations of these intelligent and adaptable animals saw them fanning out in all directions in the ensuing years. At the same time, ill-conceived, government-sponsored extermination of their most dangerous natural predator, the wolf, along with declining numbers of bears and mountain lions, gave Coyotes a significant advantage.

There are nineteen Coyote subspecies, and now, one or another, can be found just about everywhere, from mountains to deserts. They’re in every state except Hawaii and extend into Canada, Mexico, and Central America. Coyotes are still on the move—right into our cities.

Coyote physical description

Adult Coyotes generally are 30 to 40 inches long (76–102 cm) and stand 15 to 20 inches tall (38–51 cm) at the shoulder. Their tail is about 16 inches (41 cm) long. They weigh 15 to 44 pounds (7–20 kg), with males slightly larger than females. Coyotes living in desert and prairie environments are smaller than their mountain-range kin.

Coyotes have a thin face, yellow eyes, and a black nose. Like humans, their eyes are on the front of the head, giving them binocular vision. The ears are large, yellowish, triangular, and held upright.

Their body is lean, and the black-tipped, bushy tail is usually carried down, even when running. It’s only raised to a horizontal position during shows of aggression.

Warm-climate Coyotes are grayish-brown, yellowish-gray, or tawny, with a dark stripe running down the back. Those living in colder areas have a darker coat.

The front feet have five toes, and the back have four toes and a dewclaw (a rudimentary fifth toe). Coyotes have strong, muscular legs—they can run up to 40 miles per hour (64 km) and easily jump 6 to 7 feet (1.8 m) high, which means a backyard fence needs to be that high to keep them out. They’re also excellent swimmers.

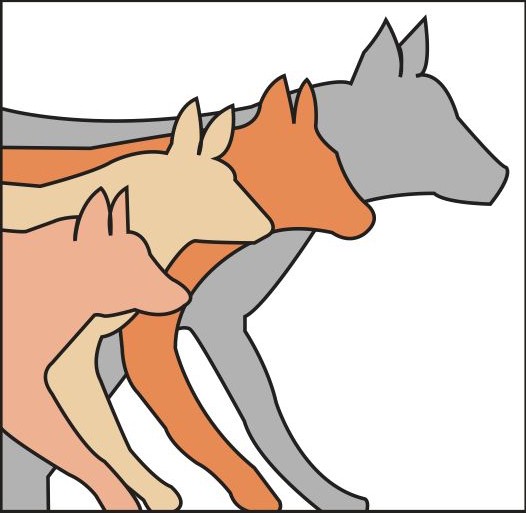

Size comparison, left, top to bottom: Gray Wolf, 80–120 lbs (36–54 kg); Red Wolf, 50–80 lbs (23–36 kg); Coyote, 15–44 lbs (7–20 kg); Red Fox, 10–15 lbs (5–7 kg). (USFWS; PD)

Senses

A Coyote’s senses are excellent, but their sense of smell triumphs over the others. Like dogs, they can smell some odors in parts per trillion.

Coyote behavior

Coyotes are nocturnal but sometimes come out in the daytime. They’re naturally shy, wary of people, and usually run away if they think they’ve been seen. Some in urban areas, however, have lost their fear of humans.

Coyotes form packs, usually consisting of a mated pair and their offspring, but there may also be unrelated others. Individuals may be forced out of a pack if they’re diseased, injured, old, or food is scarce. Being forced to live alone can be life-threatening since they lack the pack’s protection and also lose an advantage in bringing down larger prey.

Coyotes claim territories and mark posts, rocks, and trees with urine and feces. (Urban Coyotes behave the same and don’t tolerate dogs in their territory, which leads to conflict.) In rural areas, a single territory may be several square miles and typically doesn’t overlap that of another pack. When they do, the groups generally avoid each other. If a confrontation ensues, it’s usually limited to a show of aggression through body language—a flash of teeth, arched back, raised tail—and the intruder is chased away. Fighting seldom occurs; when it does, it rarely leads to death. Coyotes looking for a new territory try to stay between territorial boundaries. How to coexist–Coyote frequent questions

Communication

Coyotes are very vocal. In fact, their Latin name, Canis latrans, translates to “barking dog.” Their many calls, usually heard at dusk and night, include howls, yelps, barks, growls, and huffs. Each kind of vocalization has a particular purpose. For example, their howl, well-known to farmers and viewers of old Western movies, lets other Coyotes know where they are. Listen to Coyotes

Coyotes are really smart

ScientificAmerican.com calls Coyotes the “. . . New Top Dogs.” because they’re smart, resourceful, clever, and adaptable. Research shows Coyotes are bigger and stronger than ever before and have survived through ingenuity and exploitation of human actions affecting their environment.2 They often outsmart other wildlife and humans alike. For example, they’re known to create diversions to lure picnickers away from their food. And they sometimes drive prey toward other Coyotes waiting to ambush them. They generally live in packs but can adapt if they must live alone.

They’re now successfully living in the comfort and protection of cities and learning (mostly) to stay out of the way of humans. (Note: When urbanites feed Coyotes, it causes them to lose their fear of humans. Experts warn that this almost always leads to conflict, something nobody wants.) Living with Coyotes

Food sources

These canines are beneficial predators that help keep wildlife populations, such as rats, mice, ground squirrels, and rabbits under control. Because they eat meat, they’re considered carnivores, but in practice, they’re omnivores. In urban areas, their main diet is meat, but they’ll also eat fruit, vegetables, insects, fish, and carrion.

If your city has Coyotes, don’t leave your pets outside alone. One can easily take down a small dog or cat. Not out of malice; it just needs to eat.

They hunt by day or night and usually alone, but sometimes rural Coyotes will act as a group to take down a large animal. Unsurprisingly, they have a bad reputation among farmers and ranchers who occasionally lose young, old, or ill livestock to them.

Dens and cover

Coyotes use dens for sleeping and raising their young but seldom dig their own. They’ll use a good one for years. A suitable den for a Coyote will have more than one entrance and be located in rock crevices, caves, hollow logs, another animal’s abandoned den, or thickets. In urban areas, they may den in old sheds or large drain pipes. They don’t hibernate and are active year-round.

Reproduction

The mating season is between January and March. Many males will court a female, and she’ll choose just one. Pairs are monogamous and remain together year-round for life. (Coyotes are capable of mating with dogs and wolves, too, producing “coydogs” and “coywolves.”)

Gestation lasts about sixty-three days. Three to nine pups (usually six) are born in a den prepared by the mother. The newborns are fuzzy and helpless. Their eyes are closed for about fourteen days. Once they can see, they begin to venture outside but stay in a group. Their father plays a helpful role by bringing food to the female while she’s nursing and regurgitates food for the pups.

Pups start eating meat at about three weeks. At six to eight weeks, they stop nursing. If the mother dies before the young can eat meat, they’ll perish from starvation. If they’re able to eat meat, the father will feed and raise them. A mother, on the other hand, can rear them alone if she must, although it makes her job harder. If there are other pack members (usually older offspring), they’ll also help raise the pups.

At six to ten weeks, the mother begins taking her pups out hunting. It’s at this time that Coyotes are most visible to humans. At six months, pups are nearly full-grown and hunting on their own. Within a year (sometimes two), they leave to establish a territory, find a mate, and begin a pack of their own.

Lifespan

Most juveniles don’t live to adulthood—only 5 to 15 percent. They might live ten to fifteen years if they can survive that long, although six to eight is typical. In captivity, they can live up to eighteen years.

Coyotes and rabies

Coyotes are susceptible to rabies, but it’s rare.

Predators

Life is tough for young Coyotes. Their rates of distemper and roundworm take a heavy toll. And they’re prey for hawks, owls, and occasionally even neighboring Coyote packs. Adults are preyed on by Black Bears, Mountain Lions, and wolves, but they presently have only one predator of real consequence: humans. Hunting, traps, poison, and automobiles take a significant toll.

1 Levy, Sharon, “Coyotes are the new top dogs,” ScientificAmerican.com, May 17, 2012.

Don’t feed Coyotes; here’s why:

Feeding Coyotes does it more harm than good •

What the USDA has to say about feeding Coyotes

More reading:

Coyote: frequent questions •

Wildlife’s good mothers •

Good video about Coyotes •

Can wildlife be too smart for their own good?