Here are some interesting facts about birds. Birds are complex animals with surprising adaptations of their physical characteristics to nature. Some may have you thinking, “So that’s why they do that.”

(A special thanks to all the excellent photographers who generously allow their images to be used to enhance content like this.)

Eating and drinking

Some birds eat their prey whole

Green Herons, jays, shrikes, crows, owls, gulls, and other species swallow part or all of their prey whole. Strong stomach juices digest the soft parts. The remaining parts—bones, teeth, fur, feathers, claws, etc.—are formed into pellets that are regurgitated later. Some birds routinely vomit in the same location, leaving piles of pellets.

Owls are one of many bird species that swallow their prey whole. This photo above shows pellets from a Long-eared Owl, Asio otus, some intact and some pulled apart to show their bits of matter, including bones.

Hunger can drive desperation

The amazing photo above shows two birds of prey clasping each other; neither will let go! Why? Hunger! Great-horned Owls, Bubo virginianus, routinely prey on hawks. The Red-tailed Hawk, Buteo jamaicensis, is trying to save itself but also wants to make a meal of the owl. They may have been hungrier than usual—when it’s frigid and snowy, prey for them can be harder to find.

Great-horned Owls also prey on hares, rabbits, rodents, opossums, woodchucks, bats, weasels, other owls, and even skunks. Sometimes domestic cats, too. They’re pretty ferocious and sometimes kill more than they can eat, but they don’t let the extra food go to waste—they cache the extra to eat later.

(About the photo: Ken Lockwood, a raptor rehabilitator, was called to the scene by a bystander to separate the birds, which appeared injured. Except for ruffled feathers, the owl was fine. The hawk had leg injuries and was cared for until healed, then successfully released.)

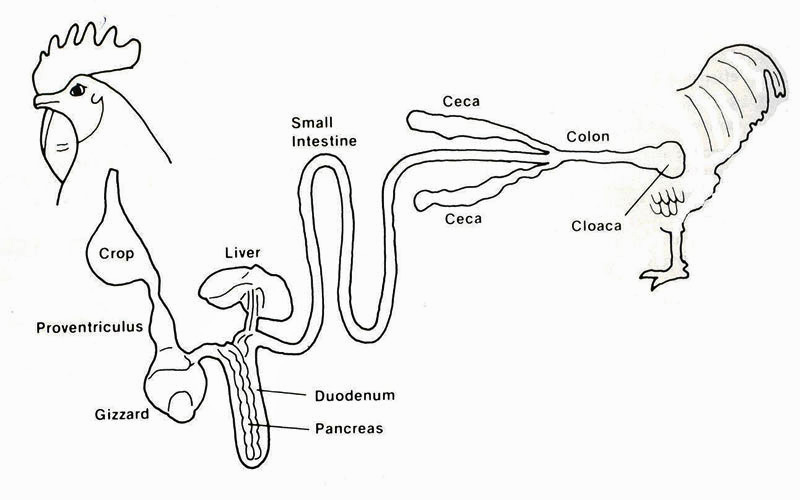

Birds don’t have teeth, so they compensate

Birds don’t have teeth to pulverize their food as humans do, so their digestive system is specialized in breaking it down. After food is swallowed, it goes into their “crop,” an enlarged pouch in the esophagus. From there, it goes into a stomach that has strong digestive juices and, from there, into the gizzard, which has strong musculature for grinding. Once it’s sufficiently converted into a digestible mash, it flows into their intestines. Sometimes, birds swallow small stones or grit to help in the grinding process.

You can leave a hummingbird feeder out in winter, and water for other birds, too

Particularly if you live in a more northern climate, it might help a late migrant or even supplement the diet of other winter visitors to leave your hummingbird feeder out. Use 1 part sugar to 4 parts water. As in summer, keep the solution fresh and the feeder clean. The solution will ferment slower in colder weather, so the feeder will need cleaning only every week or two. The nectar won’t freeze unless the air temperature drops to around 29°F (-1°C). You may want to rotate two feeders in and out to prevent freezing. If you bring a feeder indoors overnight, put it out as early as possible in the morning. Don’t forget other birds, too: they can’t drink frozen water, so a heated birdbath does them a big favor—sometimes their immediate need for liquid water is greater than their need for food.

Birds expend more energy in the winter

In the winter, birds are often forced to spend all day looking for enough calories to carry them through the night. Putting out seeds, nuts, and suet allows them to spend part of their daytime hours resting and conserving energy.

Don’t feed bread to birds

They’ll eat it, but experts say other kitchen scraps are better, as bread doesn’t contain any vital nutrients that birds need. Instead, augment birdseed and nuts with beef fat trimmings, bacon rinds, apples, grapes, potatoes, peas, and even cheese. You can also offer moistened pet food. Don’t allow foods to spoil or leave leftovers out overnight to avoid unwanted nocturnal critters. Be sure to grate or cut food into tiny pieces. No junk food!

Have you heard the one about the drunk bird?

It sounds like a joke’s coming, but there really are birds that get drunk from eating too many fermenting berries. That seems funny, only sometimes, it isn’t. Like many DUI drivers, “FUI” birds are just too drunk to fly right and can die from crashing into things. They also behave like inebriated humans: They walk in circles, topple over, lean against things for support, or bring their wings to the ground to hold themselves upright. They vomit. And they probably suffer morning-after headaches, too! Here’s a good story about a drunk Cedar Waxwing, including useful tips about how to care for an intoxicated bird, and lots of good photos, too.

Why birds suddenly disappear after weeks of spoiling them with food

Nothing beats fresh food, like berries ripening on a bush and seeds clinging to flower heads. So even in winter, the number of visitors at feeders may drop off as long as fresh foods are available. No matter how elaborate and well-filled our feeders may be, birds may scarcely give them a glance when there’s plenty of food available at its natural source.

Sleeping and resting

Where do birds go to sleep?

Usually, they go where they’ll feel safest within the same area they spend their waking hours. Some that nest on the ground also sleep there in dense cover. Others sleep hidden in trees, where they can feel the vibrations of climbing predators in time to escape. Cavity-nesting birds sleep in tree holes, chimneys, or birdhouses. Many water birds sleep on or close to water.

Some birds sleep while standing on both legs or, like Flamingos and other water birds, on one leg. Why just one leg (especially in winter)? Theories abound, but a commonly accepted one is that it conserves body heat. That’s because a bird’s legs receive three times as much blood per heartbeat as their major muscles do, so they can hold a lot of warmth close to their body.

Asleep on the wing

Some birds take short naps while flying. Laysan Albatrosses spend almost their entire lives in flight, and that includes sleeping up there, too. Another example is swifts, which are in the family Apodidae. They mate, eat, bathe while flying, and likely sleep up there, as radar planes have detected them several thousands of feet high at night.

Birds must stay alert to survive, so how do they get any rest?

We know this Swainson’s Thrush, Catharus ustulatus, has at least one eye open! (Cephas / Wikimedia; CC BY-SA 4.0)

They rest in short bits—sometimes only a few seconds long—whether napping by day or settling in for the night. Some switch between sleep and drowsing with their eyes half-open so they can still see. Some birds that migrate long stretches rest in flight by allowing half their brain to sleep while the other half keeps its eye open to stay alert—and aloft!

Singing, calling, behavior

Most daytime birds sing only when the sun’s up, but…

Most birds are daytime singers, but British researchers studying city-dwelling European Robins discovered they also sing at night. Scientists have long thought streetlights confuse birds into thinking it’s daytime, but noise has a more significant impact, as it turns out. As the daytime noise level in cities rises, the number of birds singing at night is increasing. It seems the birds are trying to be heard.

Why birds sing

Birds vocalize for several reasons. They do it to define territory, attract mates, warn of predators, stay in touch, announce the finding of food, or when begging to be fed. Some have amazingly beautiful songs, like the Northern Mockingbird. Or, powerful calls like the tiny Winter Wren, which sings at ten times the power of a crowing rooster. Some Brown Thrashers know more than 1,100 distinct songs. The male Western Sandpiper sings while performing courtship-display flying. A single Red-eyed Vireo sings up to twenty thousand songs a day!

Birds mostly sing early morning and dusk

There’s a significant reason birds sing primarily in the early morning and at dusk: That’s when the air is typically still, and the way it carries sound waves makes them clearer. There are also fewer competing background noises. Even birds heard singing during the day tend to sing more at dawn and dusk.

Do birds abandon their babies if we touch them?

Experts say the parents’ drive to nurture their offspring outweighs their fear of human scent—unless the nest is repeatedly disturbed. So, if you’re watching nestlings, it’s best to peek at them rarely and only when the parents are away.

Frenzied activity at your bird feeders before a storm

Have you noticed increased activity at your feeders before a storm? That’s because birds have a special receptor in their middle ear telling them to hurry up and take shelter. Called the Vitali organ or Paratympanic organ, it helps with their hearing and balance, but it’s also a built-in barometer. When air pressure starts falling, signaling a storm ahead, birds change their foraging patterns, social interactions, and times of activity. As for mammals, bats are the only ones with a Vitali organ (named after its discoverer, Giovanni Vitali, an anatomist). Although we humans can detect some pressure changes, birds can do it to a remarkable extent.

Why birds perch on power lines, sometimes by the hundreds

Scientists think birds perch on overhead lines because they’re not only good resting places but offer a good view, as well. And sitting close together makes for easier communication. Have you also noticed that, except for the occasional nonconformist, they sit facing the same direction? They face the wind, probably because sitting with their backs to it would ruffle their feathers, and it’s also easier for them to take off into the wind.

Different birds have different “domestic” lifestyles

Female (L) and male Pileated Woodpeckers, Dryocopus pileatus (Frank D. Lospalluto / Flickr; CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Some birds pair up only through the current nesting season. Some are polygamous and mate with several partners to ensure they spread their genes around. About 90 percent of species, however, are monogamous and stay together until one dies. The health of its mate is important to any bird, and some species may part company if one becomes frail. Blue Jays, Barn Owls, Bald Eagles, Canada Geese, and Pileated Woodpeckers are among those that mate for life.

Birds cool off by panting, bathing, finding shade

Raptors, like the Red-shouldered Hawk and Buteo lineatus, mostly get their hydration from the prey they eat but occasionally drink water. (Mike’s Birds / Flickr; CC BY-SA 2.0)

Overheating is a severe situation for most organisms. For birds, which don’t have sweat glands, the way to cool off is to pant. So, in summer, when you see them with their bills open (and oftentimes their wings spread), you’ll know they’re cooling off. They also will take baths and try to stay in the shade. A study of desert birds shows that a summer temperature rise of just 2°F (1°C) above normal can double the rate of water loss in small birds. Excessive water loss can lead to heat stroke and death. So hydration is a must for them and a good reason to provide a birdbath always filled with clean, fresh water. Unusual mass bird deaths have been reported across the U.S. in ultra-hot summers. Raptors don’t need much, if any, water since they get hydrated when they eat their prey. However, they do occasionally bathe, and even just standing in water has a cooling effect on them.

Anatomy, feathers, grooming

“Just washed my feathers and can’t do a thing with ’em”

Many birds bathe regularly, even in winter! They do it to keep their feathers clean, wash off parasites, and cool their bodies on hot days. After bathing, they use their bills to coat their feathers with a waterproof oil from a gland located under their tail feathers.

Great-horned Owls have ears — not!

They’re feathers, not ears, called ear tufts, that make the shape of this owl’s head look distinctively different from the usual. Scientists think ear tufts are used for subtle communication, signaling, or recognition. About fifty species of owls have them.

Habitat, environment

Birds suffer without water in winter

Water can be more vital than food. This Mourning Dove looks like it needed a long, satisfying drink, but what it found was ice. A birdbath with a heater can change that by giving birds access to liquid water when it’s freezing outside. (Heated birdbaths placed close to the ground will provide all animals with a drink—but thread the electric cord through a PVC pipe to protect it from chewing rodents.

How birds find food when snow covers the ground

Ground-feeding birds look for bare spots and mine them thoroughly for seeds and insects. They also explore crevices in woodpiles and rock piles and cling to old flowers to pick at their heads. If necessary, they try to scratch through the snow. Their situation can grow dire when snow is deep and long-lasting.

No, this woodpecker isn’t dead!

Spotted Woodpecker, Dendrocopos major, crouching down to eat snow (Brian Fuller / Flickr; CC BY-ND 2.0)

The Spotted Woodpecker above is crouched down, trying to eat snow because it’s such a struggle for birds to find liquid water when everything’s frozen. Covered with layers of fluffy, insulating down, they’re pretty prepared for winter’s cold temperatures. But finding water and fatty foods for energy—and plenty of it—is crucial to their survival. Small birds can’t peck through frozen ground and ice. Birds’ ability to fly farther south helps them out, and sometimes surprising birds will appear at feeders.

Birds and cats don’t mix

Are cats poaching at your bird feeders? If so, place feeders in the open, away from shrubs and other hiding places. You can also try putting a wide circle of short wire fencing around feeders. That works well, even when they’re located near shrubs: by placing the fencing just in front of the shrubs, cats may hide, but they must jump over the fence, which rustles the foliage and alerts the birds.

Cats can hide very well—sometimes by remaining motionless in plain sight. Millions of birds are killed each year by cats that have a good home and plenty of food, but they’re just doing what cats do. Hanging a bell on its collar doesn’t help—a stalking cat moves too slowly for it to ring, and when it pounces, the ringing comes too late.

If a neighbor’s cat is a problem, the solution may be as simple as asking them to keep it indoors. It’s not only safer for birds but for cats, too: Those that go outdoors have shorter lives, falling prey to cars, dogs, coyotes, and other animals, and diseases, such as feline distemper. They can also get lost, stolen, or poisoned.

All about birds

Provide water for wildlife

In your yard: 27 birds to look for

In your yard: a look at garter snakes